Indonesia’s historical narrative has been molded by its geographic location, abundant natural resources, a series of human migrations and interactions, conquests, the early arrival of Islam from Sumatra in the 7th century AD, and the emergence of Islamic kingdoms. The nation’s strategic position as a hub for sea trade has played a central role in shaping its history. Indonesia’s vast expanse is home to diverse populations with distinct migration backgrounds, resulting in a rich tapestry of cultures, ethnicities, and languages. The archipelago’s geography and climate have played a crucial role in agriculture, trade, and the formation of states. The modern boundaries of Indonesia align with the 20th-century borders of the Dutch East Indies.

The Austronesian people, constituting the majority of the present-day population, are believed to have originated in Taiwan and migrated to Indonesia around 2000 BCE. In the 7th century CE, the influential Srivijaya maritime kingdom thrived, bringing Hindu and Buddhist influences to the region. Subsequently, the agricultural dynasties of the Buddhist Sailendra and Hindu Mataram prospered and waned in inland Java. The last significant pre-Islamic kingdom, the Hindu Majapahit kingdom, reached its zenith in the late 13th century and extended its influence across much of Indonesia. The earliest traces of Islamized communities in Indonesia can be traced back to the 13th century in northern Sumatra. Over time, various regions in Indonesia gradually adopted Islam, which became the predominant religion in Java and Sumatra from the late 12th century to the 16th century. Islam often intermingled with preexisting cultural and religious traditions.

European powers, notably the Portuguese, began arriving in Indonesia in the 16th century with the aim of controlling the lucrative trade in spices like nutmeg, cloves, and cubeb pepper in the Maluku Islands. In 1602, the Dutch established the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and rapidly emerged as the dominant European force by 1610. However, the VOC faced financial troubles and was officially dissolved in 1800. Subsequently, the Dutch government took direct control over the Dutch East Indies.

By the early 20th century, Dutch influence extended throughout the region. The Japanese invasion and occupation from 1942 to 1945 during World War II marked the end of Dutch rule and invigorated the previously suppressed Indonesian independence movement. Just two days after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Sukarno, a prominent nationalist leader, declared Indonesia’s independence and assumed the presidency. The Netherlands attempted to regain control, sparking a bitter armed and diplomatic conflict that concluded in December 1949 when, under international pressure, the Dutch officially acknowledged Indonesia’s independence.

In 1965, there was an attempted coup that resulted in a v!olent anti-communist purge led by the army, leading to the tragic death of over half a million people. General Suharto managed to outmaneuver President Sukarno politically and assumed the presidency in March 1968. His administration, known as the New Order, gained the favor of Western countries, whose investments played a significant role in the substantial economic growth experienced over the following three decades.

However, Indonesia was severely affected by the East Asian Financial Crisis in the late 1990s, leading to widespread protests and General Suharto’s resignation on May 21, 1998. The Reformasi era, which began after Suharto’s resignation, ushered in a strengthening of democratic processes, including a regional autonomy program, the secession of East Timor, and Indonesia’s first direct presidential election in 2004.

While there have been significant strides in democratization, the country has faced challenges such as political and economic instability, social unrest, corruption, natural disasters, and terror!sm, which have impeded progress. Although Indonesia generally enjoys harmonious relations among different religious and ethnic groups, some regions continue to grapple with sectarian tensions and occasional violence.

2000 BCE – 2023

HISTORY OF INDONESIA

The history of Indonesia has been significantly influenced by its geographic position, abundant natural resources, various human migrations, conquests, the spread of Islam from Sumatra in the 7th century AD, and the emergence of Islamic kingdoms. Indonesia’s strategic location as a sea-lane crossroads has historically fostered inter-island and international trade, which played a fundamental role in shaping its history. The region’s rich cultural diversity is the result of its multicultural population, formed through multiple migrations, contributing to a tapestry of cultures, ethnicities, and languages. The archipelago’s unique landforms and climate have profoundly influenced agriculture, trade, and the formation of states. The contemporary boundaries of Indonesia align with the 20th-century borders of the former Dutch East Indies.

Around 2000 BCE, Austronesian people, believed to originate from Taiwan, arrived in Indonesia, forming the majority of the current population. In the 7th century CE, the powerful Srivijaya naval kingdom thrived, bringing with it Hindu and Buddhist influences. Successive dynasties, the Buddhist Sailendra and Hindu Mataram, flourished and waned in inland Java. The Hindu Majapahit kingdom emerged as the last significant non-Muslim realm, flourishing from the late 13th century and extending its influence over much of Indonesia. The earliest traces of Islamized communities in Indonesia date back to the 13th century in northern Sumatra, with the Islamic faith gradually spreading to other parts of the archipelago. By the late 16th century, Islam had become the predominant religion in Java and Sumatra, intermingling with existing cultural and religious traditions.

European nations, including the Portuguese, arrived in Indonesia during the 16th century, driven by the desire to monopolize the sources of valuable spices like nutmeg, cloves, and cubeb pepper in the Maluku Islands. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was established by the Dutch and swiftly emerged as the dominant European power by 1610. Following a period of economic hardship, the VOC was officially dissolved in 1800, and the Dutch government assumed control over the Dutch East Indies. Dutch dominance extended to encompass the modern territorial boundaries by the early 20th century. However, this colonial rule was interrupted when Japan invaded and occupied Indonesia during World War II from 1942 to 1945, ultimately ending Dutch sovereignty and nurturing the suppressed Indonesian independence movement. Just two days after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, nationalist leader Sukarno proclaimed independence and became the country’s first president. The Netherlands attempted to regain control but, under international pressure, officially recognized Indonesian independence in December 1949.

The mid-1960s witnessed an attempted coup that triggered a v!olent army-led anti-communist purge, resulting in the tragic death of over half a million people. General Suharto adeptly outmaneuvered President Sukarno and assumed the presidency in March 1968. Suharto’s New Order administration was well-received by Western nations, whose investments significantly contributed to three decades of robust economic growth in Indonesia. However, the late 1990s brought the East Asian Financial Crisis, hitting Indonesia the hardest and leading to popular protests, culminating in Suharto’s resignation on May 21, 1998.

The post-Suharto Reformasi era witnessed the strengthening of democratic processes, the introduction of a regional autonomy program, the secession of East Timor, and the first direct presidential election in 2004. Yet, Indonesia has faced challenges, including political and economic instability, social unrest, corruption, natural disasters, and terror!sm, which have impeded its progress. Although different religious and ethnic groups generally coexist harmoniously, some regions continue to grapple with sectarian tensions and sporadic v!olence.

Throughout this evolving history, Indonesia’s people and culture have been shaped by a rich tapestry of influences, including early animistic beliefs and the development of advanced wet rice cultivation, which contributed to the rise of well-organized societies by the 1st century CE. The fertile lands of Java, with their favorable climate and abundant rainfall, were especially conducive to wet rice cultivation, ultimately leading to the growth of villages, towns, and small kingdoms. These early societies often had their own ethnic and tribal religions. Java’s ideal agricultural conditions necessitated complex social structures to support the cultivation of wet rice, making it more advanced compared to the simpler form of dry-field rice farming.

Tarumanagara

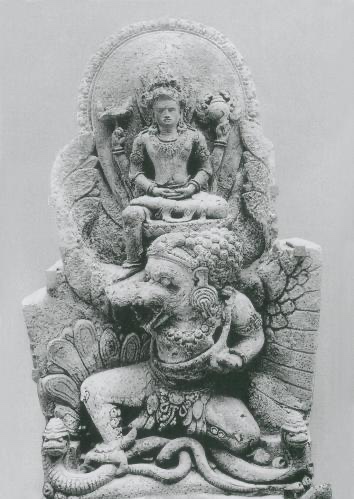

Indonesia, much like the broader Southeast Asian region, experienced a profound influence of Indian culture. Starting from the 2nd century and continuing through the subsequent centuries, the presence of Indian dynasties such as the Pallava, Gupta, Pala, and Chola facilitated the diffusion of Indian culture across Southeast Asia.

One notable example of this Indianization is the Tarumanagara, or simply Taruma Kingdom, an early Sundanese kingdom in western Java. Its 5th-century ruler, Purnawarman, is credited with producing some of the earliest known inscriptions in Java, which are believed to have originated around 450 CE.

In the Western Java region, close to Bogor and Jakarta, at least seven stone inscriptions linked to the Tarumanagara Kingdom have been uncovered. These inscriptions include Ciaruteun, Kebon Kopi, Jambu, Pasir Awi, and Muara Cianten, all located near Bogor, as well as the Tugu inscription near Cilincing in North Jakarta, and the Cidanghiang inscription in Lebak village, Munjul district, to the south of Banten. These inscriptions stand as significant historical artifacts, bearing testimony to the cultural exchange between India and Indonesia during this era.

Kalingga Kingdom

Kalingga, which existed during the 6th century, was an Indianized kingdom situated on the northern coast of Central Java, Indonesia. It holds the distinction of being the earliest Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in Central Java. Alongside Kutai, Tarumanagara, Salakanagara, and Kandis, Kalingga is among the oldest kingdoms in the history of Indonesia. These kingdoms collectively represent significant milestones in the early history of the Indonesian archipelago.

Sunda Kingdom

The Sunda Kingdom was a Hindu kingdom of Sundanese origin situated in the western region of the Java island. It thrived from 669 until approximately 1579, encompassing the present-day areas of Banten, Jakarta, West Java, and the western portion of Central Java. Throughout its history, the Sunda Kingdom relocated its capital multiple times, shifting between the Galuh (Kawali) region in the east and Pakuan Pajajaran in the west. The Kingdom reached its zenith during the rule of King Sri Baduga Maharaja, whose reign, spanning from 1482 to 1521, is renowned as a period of peace and prosperity among the Sundanese people. The predominant ethnic group in the kingdom was the Sundanese, and Hinduism was the prevailing religion.

Srivijaya Empire

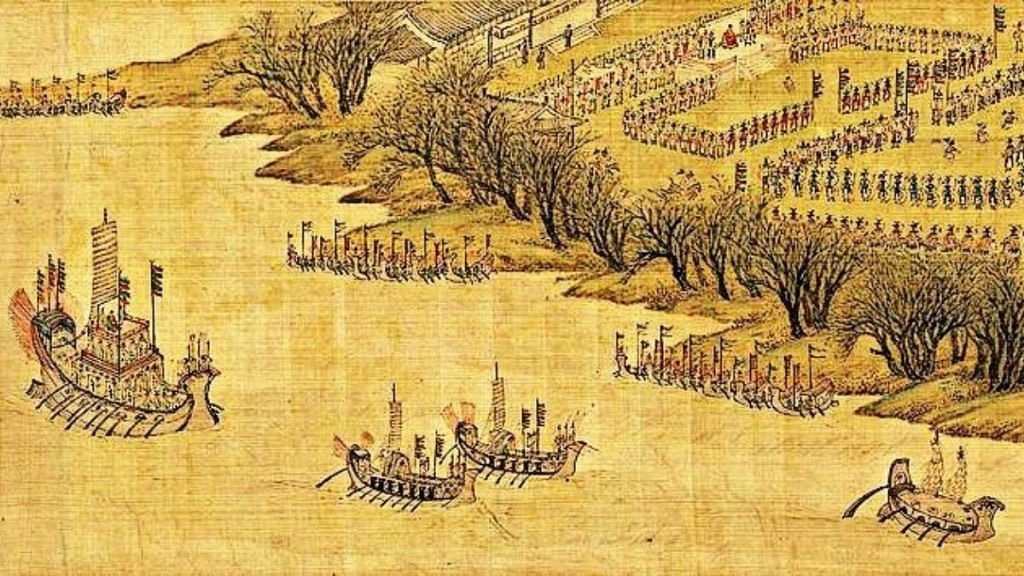

Srivijaya was a significant thalassocratic empire with its base on the island of Sumatra, exerting influence over much of Southeast Asia. From the 7th to the 12th century AD, Srivijaya played a pivotal role in the propagation of Buddhism. It was the first political entity to dominate large parts of western Maritime Southeast Asia. Geographically situated, Srivijaya harnessed advanced maritime technology and relied extensively on trade, transforming its economy into one based on prestige goods.

The earliest known mention of Srivijaya dates back to the 7th century. A Chinese monk from the Tang dynasty, Yijing, reported visiting Srivijaya in the year 671 for an extended period. The first known inscription featuring the name Srivijaya dates to the 7th century and was found in the Kedukan Bukit inscription near Palembang, Sumatra, dating to June 16, 682. Between the late 7th and early 11th centuries, Srivijaya rose to become a dominant force in Southeast Asia, engaging in intricate interactions, sometimes rivalries, with neighboring powers like Mataram, Khmer, and Champa. Srivijaya’s significant foreign relationships included profitable trade agreements with China, spanning from the Tang to the Song dynasty, as well as religious, cultural, and trade connections with the Buddhist Pala of Bengal and the Islamic Caliphate in the Middle East.

Until the 12th century, Srivijaya primarily operated as a land-based polity, utilizing its fleets for logistical support in advancing its land-based influence. With changing dynamics in the maritime Asian economy and the risk of losing its dependencies, Srivijaya adopted a naval strategy aimed initially at influencing trading ships to call at its port. Later, this strategy evolved into raiding fleets.

The kingdom ultimately disintegrated in the 13th century, driven by several factors, including the expansion of competing Javanese empires like Singhasari and Majapahit. After the fall of Srivijaya, it faded into obscurity and was not widely acknowledged until 1918 when French historian George Cœdès, from the École française d’Extrême-Orient, formally proposed its existence.

Mataram Kingdom

The Mataram Kingdom, a Javanese Hindu-Buddhist realm thriving from the 8th to the 11th centuries, was initially centered in Central Java, later expanding to East Java. It was established by King Sanjaya and ruled by both the Shailendra and Ishana dynasties.

Throughout its history, the kingdom primarily depended on agriculture, particularly extensive rice cultivation, and later benefited from maritime trade. Foreign records and archaeological discoveries suggest that it was well-populated and prosperous, fostering a complex society, a rich culture, and a refined civilization.

Between the late 8th and mid-9th centuries, the Mataram Kingdom witnessed the zenith of classical Javanese art and architecture, reflected in the rapid construction of temples like Kalasan, Sewu, Borobudur, and Prambanan, all situated near the modern city of Yogyakarta. At its peak, the kingdom became a dominant empire, extending its influence not only in Java but also in Sumatra, Bali, southern Thailand, Indianized realms in the Philippines, and Cambodia’s Khmer Empire.

Later, the dynasty fragmented into two realms based on religious patronage, with the Buddhist and Shaivite dynasties. Civil war ensued, resulting in the division of the Mataram Kingdom into two powerful realms: the Shaivite dynasty of Mataram in Java under Rakai Pikatan and the Buddhist dynasty of Srivijaya in Sumatra led by Balaputradewa.

Hostilities persisted until 1016 when the Shailendra clan, based in Srivijaya, incited a rebellion by Wurawari, a vassal of the Mataram Kingdom, leading to the sacking of the capital of Watugaluh in East Java. Srivijaya rose as the undisputed hegemonic empire in the region, while the Shaivite dynasty endured, reclaiming East Java in 1019 and establishing the Kahuripan Kingdom, led by Airlangga, the son of Udayana of Bali.

Kahuripan Kingdom

Kahuripan, an 11th-century Javanese Hindu-Buddhist realm, had its capital situated in the estuarine region of the Brantas River valley in East Java. This kingdom’s existence was relatively brief, spanning only from 1019 to 1045, and it was solely ruled by Airlangga. Kahuripan emerged from the remnants of the Kingdom of Mataram following the invasion by Srivijaya. In 1045, Airlangga chose to abdicate in favor of his two sons, ultimately dividing the realm into Janggala and Panjalu (Kadiri).

Subsequently, during the 14th and 15th centuries, this former kingdom earned recognition as one of Majapahit’s 12 provinces.

Chola Invasion Of Srivijaya

For the most part of their intertwined history, ancient India and Indonesia maintained amicable and peaceful relations, making this Indian invasion a rare occurrence in Asian history. During the 9th and 10th centuries, Srivijaya enjoyed close ties with the Pala Empire in Bengal. An inscription from 860 CE at Nalanda records Maharaja Balaputra of Srivijaya dedicating a monastery in Pala territory at the Nalanda Mahavihara. Relations between Srivijaya and the Chola dynasty of southern India were harmonious during the reign of Raja Raja Chola I. However, under the rule of Rajendra Chola I, relations soured as Chola naval raids targeted Srivijayan cities.

The Cholas were known to benefit from both piracy and foreign trade. At times, Chola seafaring led to outright plunder and conquest, extending as far as Southeast Asia. Srivijaya controlled strategic naval choke points, such as the Malacca and Sunda Straits, and was a significant trading empire with formidable naval forces. The northwest entrance to the Malacca Strait was overseen from Kedah on the Malay Peninsula side and Pannai on the Sumatran side. Meanwhile, Malayu (Jambi) and Palembang held command over the southeast entrance and the Sunda Strait. They practiced a naval trade monopoly, compelling passing trade vessels to visit their ports or face the threat of plunder.

The exact motivations behind this naval expedition remain uncertain. Historian Nilakanta Sastri suggested that the attack might have been triggered by Srivijayan efforts to obstruct Chola trade with the East, particularly China. Alternatively, it could have been Rajendra’s desire to extend his influence across the sea, a venture well-known to his subjects at home, adding to his prestige. The Cholan invasion ultimately led to the downfall of the Sailendra Dynasty of Srivijaya.

Kediri Kingdom

The Kingdom of Kediri, a Hindu-Buddhist realm in East Java, thrived from around 1042 to 1222. It succeeded Airlangga’s Kahuripan kingdom and is viewed as a continuation of the Isyana Dynasty in Java. In 1042, Airlangga divided his Kahuripan realm into Janggala and Panjalu (Kadiri) and chose to abdicate, allowing his sons to rule while he pursued an ascetic lifestyle.

Kediri coexisted with the Srivijaya empire in Sumatra during the 11th to 12th centuries and maintained trade relations, notably with China and, to some extent, India. Chinese accounts referred to this kingdom as Tsao-wa or Chao-wa (Java), and numerous Chinese records indicate that Chinese explorers and traders frequented this region. Relations with India were largely cultural, with Javanese poets and scholars composing works inspired by Hindu mythology, beliefs, and epics such as the Mahabharata and Ramayana.

In the 11th century, Srivijayan dominance in the Indonesian archipelago began to wane, marked by the Rajendra Chola invasion of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra. The Chola king from Coromandel conquered Kedah, previously under Srivijaya’s control. The decline of Srivijayan influence facilitated the emergence of regional kingdoms like Kediri, which relied more on agriculture than trade. Later, Kediri successfully controlled the spice trade routes to Maluku.

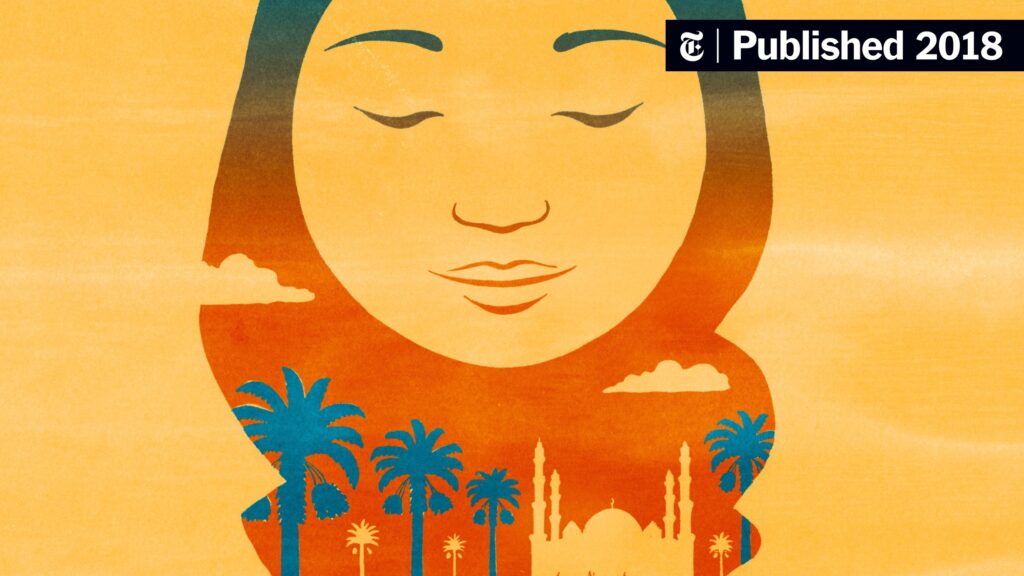

The Era of Islamic States

Evidence suggests that Arab Muslim traders started arriving in Indonesia as early as the 8th century. However, the significant spread of Islam in the region did not commence until the late 13th century. Initially, Islam was introduced by Arab Muslim traders and subsequently through the efforts of scholars. Its progress was further facilitated by the acceptance of local rulers and the conversion of the elites. These early missionaries came from various countries and regions, including South Asia (e.g., Gujarat), Southeast Asia (e.g., Champa), and later from the southern Arabian Peninsula (e.g., Hadhramaut).

In the 13th century, Islamic communities began to take root on the northern coast of Sumatra. Notably, Marco Polo, during his return journey from China in 1292, reported encountering at least one Muslim town. The earliest recorded Muslim ruler, Sultan Malik al Saleh, from the Samudera Pasai Sultanate, had a gravestone dated AH 696 (AD 1297). By the close of the 13th century, Islam had firmly established itself in Northern Sumatra.

By the 14th century, Islam had taken hold in northeast Malaya, Brunei, the southwestern Philippines, and had found acceptance in some courts along the coastal regions of East and Central Java. By the 15th century, Islam had spread to Malacca and other parts of the Malay Peninsula. During this period, the Hindu Majapahit Empire of Java saw a decline as Muslim traders from various regions, including Arabia, India, Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and China, began to dominate the trade routes previously controlled by Javanese Majapahit traders.

The Chinese Ming dynasty played a pivotal role, supporting Malacca and leading to the establishment of a Chinese Muslim settlement in Palembang and the northern coast of Java during the voyages of Zheng He (1405 to 1433). Malacca actively promoted the conversion to Islam, while the Ming fleet contributed to the formation of Chinese-Malay Muslim communities in the northern coastal regions of Java, creating a permanent contrast to the Hindu presence in Java.

By 1430, these expeditions had introduced Muslim Chinese, Arab, and Malay communities to northern ports in Java, such as Semarang, Demak, Tuban, and Ampel, marking the growing influence of Islam on the northern coast of Java. Malacca thrived under Chinese Ming protection, while the Majapahit Empire faced a steady decline. Notable Muslim kingdoms of this era included Samudera Pasai in northern Sumatra, Malacca Sultanate in eastern Sumatra, Demak Sultanate in central Java, Gowa Sultanate in southern Sulawesi, and the sultanates of Ternate and Tidore in the Maluku Islands to the east.

Singhasari Kingdom

Singhasari, a Javanese Hindu kingdom, thrived in eastern Java from 1222 to 1292, succeeding the Kingdom of Kediri as the dominant power in the region. The kingdom was founded by Ken Arok (1182–1227/1247), whose legend remains popular in Central and East Java.

In 1275, during the reign of King Kertanegara, the fifth ruler of Singhasari since 1254, a peaceful naval campaign was launched northward. This expedition aimed to counter continuous Ceylon pirate raids and the Chola kingdom’s invasion from India, which had conquered Srivijaya’s Kedah in 1025. Among the Malayan kingdoms, the most robust was Jambi, which had captured Srivijaya’s capital in 1088, followed by the Dharmasraya kingdom and the Temasek kingdom in Singapore.

The Pamalayu expedition spanning from 1275 to 1292, transitioning from Singhasari to Majapahit, is documented in the Javanese Nagarakrtagama scroll. This expanded Singhasari’s realm into Majapahit territory. In 1284, King Kertanegara led a military expedition to Bali, effectively integrating it into Singhasari’s domain. The king also dispatched troops, missions, and emissaries to neighboring kingdoms, including the Sunda-Galuh kingdom, Pahang kingdom, Balakana kingdom (Kalimantan/Borneo), and Gurun kingdom (Maluku). An alliance was established with the king of Champa (Vietnam).

In 1290, King Kertanegara eradicated any remaining Srivijayan influence from Java and Bali. However, the extensive campaigns depleted a significant portion of the kingdom’s military forces and eventually led to a treacherous conspiracy against the unsuspecting King Kertanegara. Situated at the heart of the Malayan peninsula trade routes, the growing power, influence, and wealth of the Javanese Singhasari empire came to the attention of Kublai Khan of the Mongol Yuan dynasty in China.

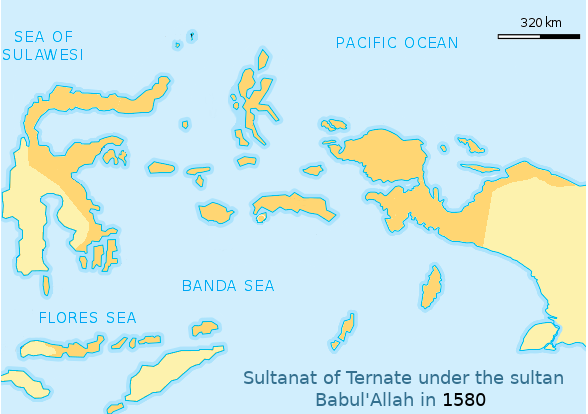

Sultanate Of Ternate

The Sultanate of Ternate, along with Tidore, Jailolo, and Bacan, is among Indonesia’s ancient Muslim kingdoms. Ternate’s origins trace back to 1257, when Momole Cico, bearing the title Baab Mashur Malamo, founded the kingdom. Its zenith came during the rule of Sultan Baabullah (1570–1583), a period when it held sway over a significant portion of eastern Indonesia and part of the southern Philippines. Ternate, known for its abundant clove production, held regional influence from the 15th to the 17th centuries.

Majapahit Empire

Majapahit, a Hindu-Buddhist thalassocratic empire situated on Java Island, thrived in Southeast Asia from 1293 to around 1527. Its zenith unfolded under the rule of Hayam Wuruk, reigning from 1350 to 1389, marked by far-reaching conquests across Southeast Asia. The credit for these achievements is often shared with his prime minister, Gajah Mada. The Nagarakretagama (Desawarñana) of 1365 described Majapahit as an empire with 98 tributaries, stretching from Sumatra to New Guinea, encompassing present-day Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, southern Thailand, Timor Leste, and the southwestern Philippines (especially the Sulu Archipelago). Nonetheless, the extent of Majapahit’s sphere of influence remains a topic of historical debate.

Majapahit stands as one of the last significant Hindu-Buddhist empires in the region and is renowned as one of the most formidable empires in the histories of Indonesia and Southeast Asia. It’s often viewed as a precursor to modern Indonesia’s boundaries, and its impact extended beyond the present-day borders, sparking numerous scholarly inquiries.

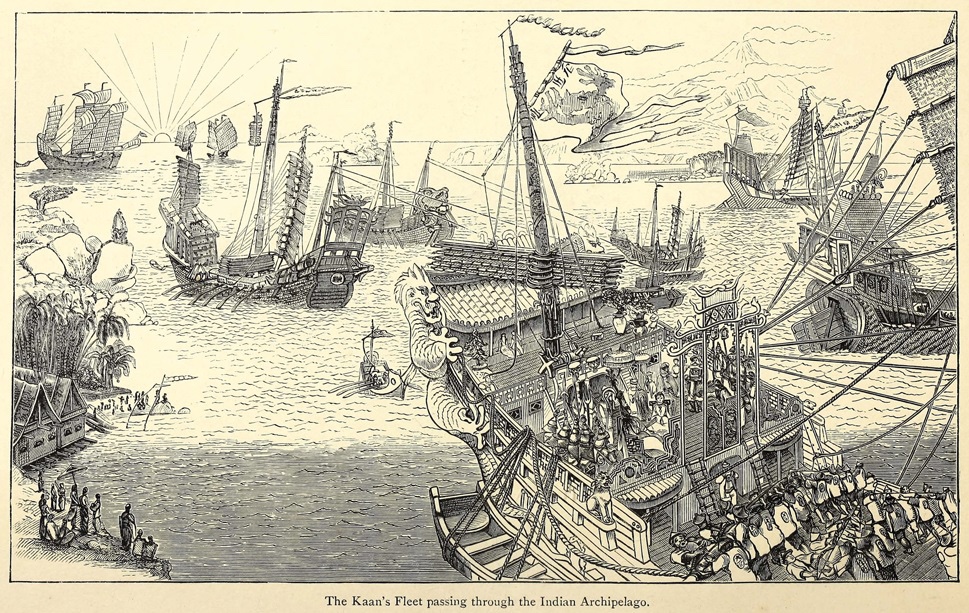

Mongol Invasion Of Java

In 1292, during the Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan, an ambitious campaign was launched to invade Java, an island in what is now Indonesia, with a formidable force of 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers. This expedition was a punitive response to Kertanegara of Singhasari, who had both refused to pay tribute to the Yuan and harmed one of their envoys. Kublai Khan’s strategy was to subdue Singhasari, believing that this victory would lead neighboring regions to submit to Yuan authority. The Yuan dynasty’s control over vital Asian sea trade routes would then be secured due to the strategic importance of the archipelago.

However, by the time the Yuan forces arrived in Java, a shift had occurred. Kertanegara had been assass!nated, and Singhasari had been taken over by Kediri. Consequently, the Yuan expedition’s objective shifted towards compelling the successor state, Kediri, to acknowledge Yuan dominance. Despite a hard-fought campaign, Kediri eventually capitulated, only to betray the Yuan forces through their former ally, Majapahit, led by Raden Wijaya. In the end, the invasion ended in failure for the Yuan dynasty and a triumph for the emerging power, Majapahit.

The Colonial Era

In 1511, the Capture of Malacca transpired when Afonso de Albuquerque, the governor of Portuguese India, successfully seized the city of Malacca. This pivotal port city held sway over the strategically vital Strait of Malacca, a narrow passage through which all maritime trade between China and India flowed.

The conquest of Malacca was the realization of a grand design crafted by King Manuel I of Portugal, who had sought to outpace the Castilians in reaching the Far East since 1505. Simultaneously, it aligned with Albuquerque’s vision of establishing enduring Portuguese influence in the Indian Ocean, alongside strongholds like Hormuz, Goa, and Aden. This comprehensive approach aimed to control trade routes and counter Muslim shipping.

Embarking on their expedition from Cochin in April 1511, the Portuguese faced the challenge of unfavorable monsoon winds. Should their mission falter, they would be stranded without the possibility of reinforcements and a return to their bases in India. This endeavor marked one of the most distant territorial conquests in human history up to that point.

In 1595, the Inaugural Dutch Expedition to the East Indies took place.

During the 16th century, the spice trade held immense profitability, yet the Portuguese Empire maintained a firm grip on the spice-rich source, Indonesia. Initially, Dutch merchants were content to purchase spices in Lisbon, Portugal, where they could still turn a decent profit by selling these spices throughout Europe. However, in the 1590s, the Netherlands found itself at odds with Spain, which was in a dynastic union with Portugal, rendering ongoing trade virtually impossible.

This situation was unacceptable to the Dutch, who sought to break free from the Portuguese monopoly and establish direct access to Indonesia. The First Dutch Expedition to the East Indies, spanning from 1595 to 1597, played a pivotal role in opening up the Indonesian spice trade to Dutch merchants, ultimately leading to the formation of the Dutch East India Company. It also signified the decline of Portuguese dominance in the region.

From January 1, 1610, to 1797, the Dutch East Indies witnessed a period of Company Rule under Dutch governance.

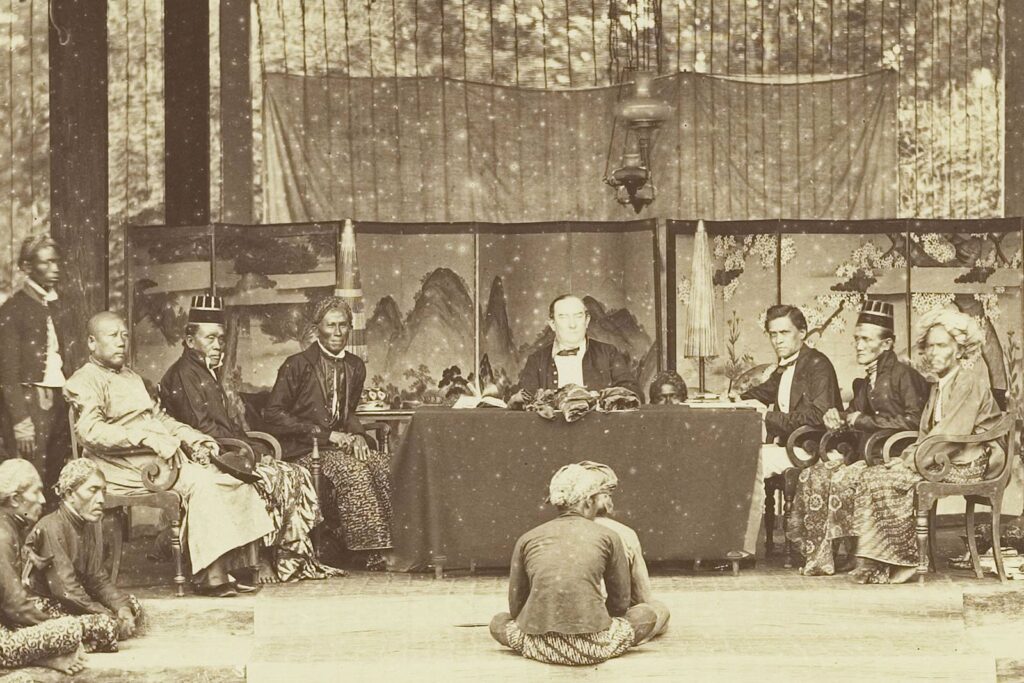

Company rule in the Dutch East Indies commenced with the Dutch East India Company appointing its inaugural governor-general in 1610 and drew to a close in 1800. It culminated with the company’s financial collapse and the subsequent nationalization of its holdings as the Dutch East Indies. During this time, the Dutch East India Company established firm territorial authority across much of the archipelago, most notably on Java.

The foundation of the first enduring Dutch trading post in Indonesia dates back to 1603 in Banten, situated in northwest Java. Subsequently, Batavia was designated as the capital from 1619 onwards. Unfortunately, issues such as corruption, warfare, smuggl!ng, and mismanagement contributed to the company’s insolvency by the late 18th century. In 1800, the company was formally dissolved, and its colonial assets were taken over by the Batavian Republic, forming the Dutch East Indies.

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, comprising present-day Indonesia, emerged as a Dutch colony. It was forged from the trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which transitioned under Dutch government oversight in 1800.

Throughout the 19th century, Dutch influence and dominion expanded, culminating in its broadest territorial reach during the early 20th century. The Dutch East Indies held a position of immense value among European colonies, significantly contributing to the Netherlands’ global prominence in the spice and cash crop trade from the 19th to the early 20th centuries.

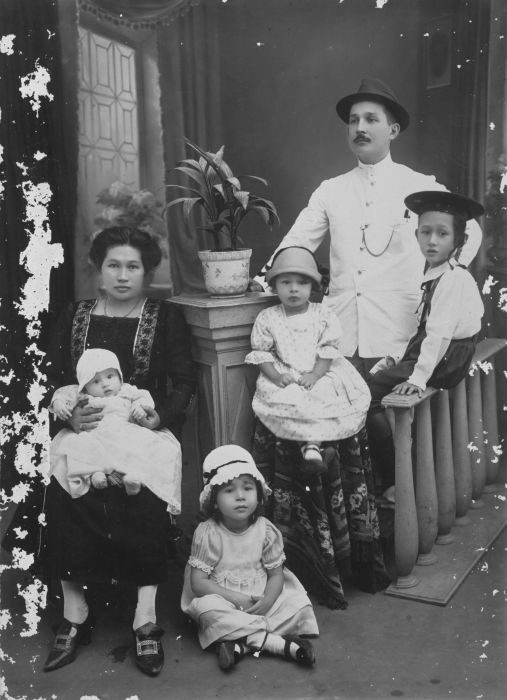

This colonial era was characterized by a rigid social order founded on racial and social hierarchies, with a Dutch elite residing separately yet interconnected with the indigenous population. The term “Indonesia” gained prominence for the geographical region after 1880. In the early 20th century, local intellectuals began to develop the idea of Indonesia as a nation-state, setting the groundwork for an independence movement.

Padri War

The Padri War raged on from 1803 to 1837 in West Sumatra, Indonesia, pitting the Padri against the Adat. The Padri were Muslim clerics hailing from Sumatra with the aim of instituting Sharia law in the Minangkabau region of West Sumatra. The Adat, on the other hand, encompassed the Minangkabau nobility and traditional leaders. Seeking assistance, the Adat sought the aid of the Dutch, who intervened in 1821 and supported the nobility in quelling the Padri faction.

Invasion Of Java

The 1811 Invasion of Java marked a victorious British amphibious operation against the Dutch East Indian island of Java, occurring between August and September 1811 amid the Napoleonic Wars. Initially established as a colony of the Dutch Republic, Java remained under Dutch control throughout the tumultuous period of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

During this time, the French had invaded the Dutch Republic, leading to the establishment of the Batavian Republic in 1795 and the Kingdom of Holland in 1806. Subsequently, in 1810, the Kingdom of Holland was absorbed into the First French Empire, rendering Java a nominally French colony while it continued to be primarily governed and defended by Dutch personnel.

Following the success of British campaigns against French colonies in the West Indies in 1809 and 1810, as well as their effective operations in Mauritius during the same period, attention shifted to the Dutch East Indies. In April 1811, an expedition was dispatched from India, and a small squadron of frigates patrolled off the island, conducting raids on shipping and launching amphibious assaults as opportunities arose. On August 4, troops were landed, and by August 8, the unguarded city of Batavia surrendered. The defending forces retreated to the fortified position of Fort Cornelis, which the British besieged and captured in the early hours of August 26.

The remaining defenders, a combination of Dutch and French regulars along with native militiamen, withdrew, with the British in pursuit. A series of amphibious and land-based assaults led to the capture of most remaining strongholds. On September 16, the city of Salatiga surrendered, followed by the official surrender of the entire island to the British on September 18.

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, inked in London on August 13, 1814, sealed the agreement between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. This treaty marked the return of numerous territories in the Moluccas and Java to Dutch control, which had been captured by Britain during the Napoleonic Wars. However, the treaty also affirmed British sovereignty over the Cape Colony at the southern tip of Africa and certain portions of South America. The signatories were Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, representing the British, and diplomat Hendrik Fagel, representing the Dutch.

Java War

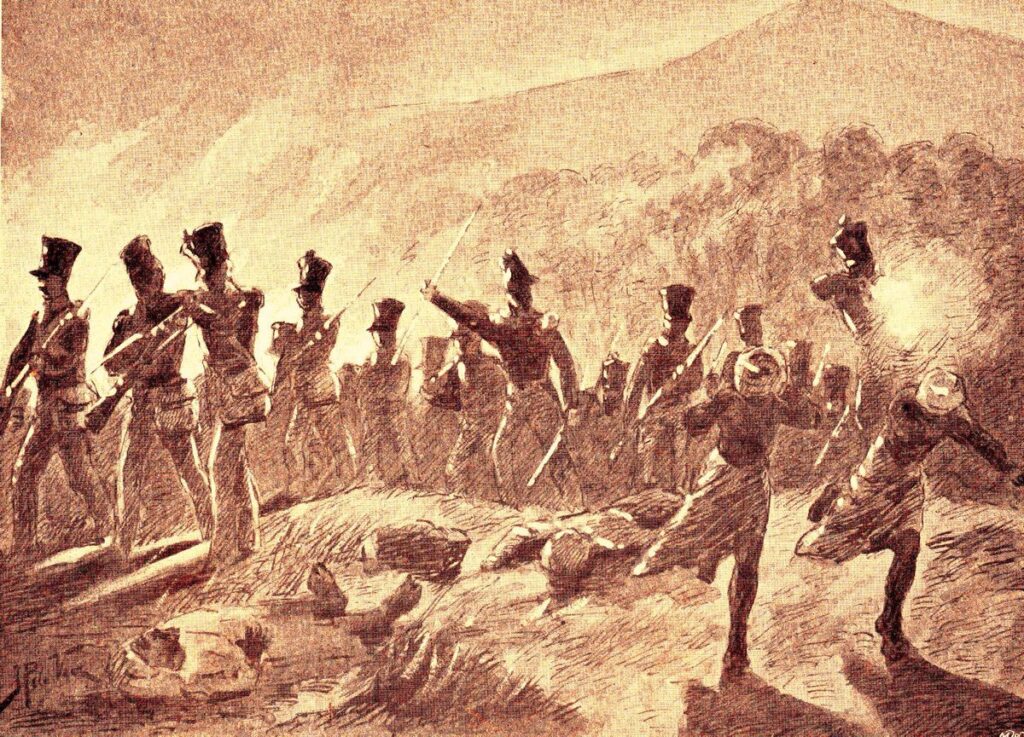

The Java War unfolded in central Java from 1825 to 1830, pitting the colonial Dutch Empire against indigenous Javanese insurgents. This conflict initially sprang from a rebellion led by Prince Diponegoro, a prominent figure in the Javanese aristocracy who had formerly collaborated with the Dutch.

The rebel forces laid siege to Yogyakarta, a strategic move that hindered a swift resolution. This respite allowed the Dutch to bolster their forces with colonial and European troops, ultimately lifting the siege in 1825. Subsequent to this setback, the rebels persisted in waging a guerrilla warfare campaign for five more years.

The culmination of the war saw a Dutch triumph, followed by an invitation for Prince Diponegoro to attend a peace conference. However, he was ultimately betrayed and captured. Given the extensive cost of the conflict, Dutch colonial authorities instated significant reforms throughout the Dutch East Indies to secure continued profitability in their colonies.

System of Cultivation

Despite the increasing returns from the Dutch land tax system, Dutch finances faced significant strains due to the costs incurred during the Java War and Padri Wars. The outbreak of the Belgian Revolution in 1830, coupled with the ongoing expenses associated with maintaining the Dutch army at a wartime footing until 1839, brought the Netherlands perilously close to financial collapse. In response to these challenges, in 1830, a new governor-general, Johannes van den Bosch, was appointed with the goal of intensifying the exploitation of the Dutch East Indies’ resources.

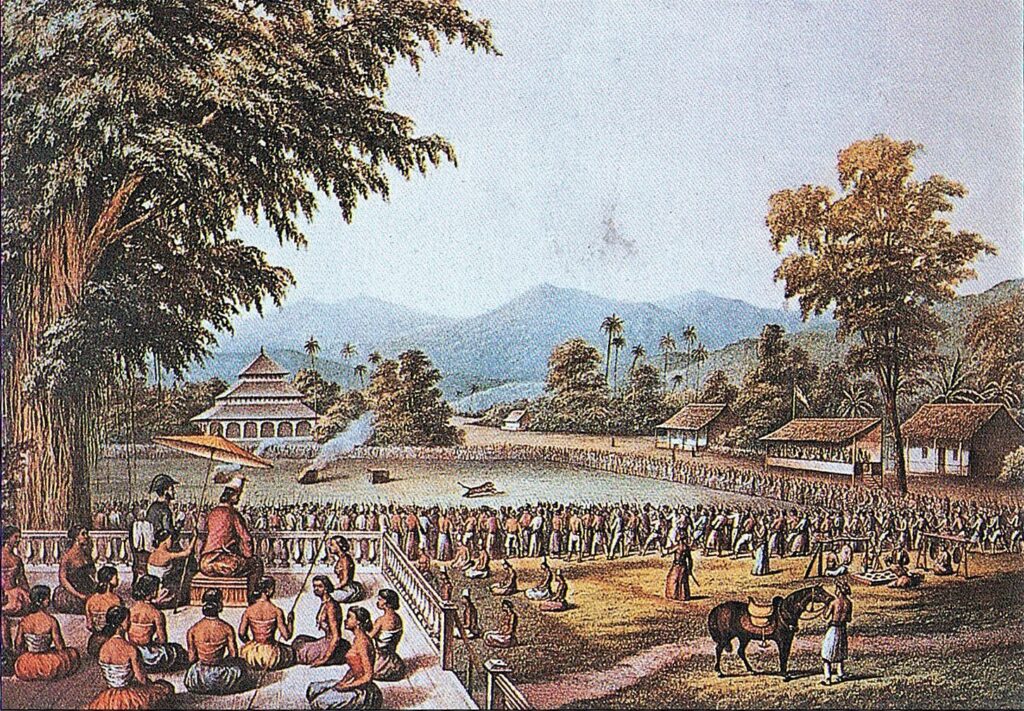

The cultivation system was predominantly implemented in Java, the core of the colonial administration. Instead of traditional land taxes, the government mandated that 20% of village land be dedicated to cultivating crops for export, or, alternatively, villagers were obligated to work on government-owned plantations for 60 days each year. These policies, however, led to more formal ties between Javanese villagers and their communities and, at times, restricted their ability to move freely around the island without permission. Consequently, much of Java was transformed into Dutch plantations. Although theoretically, only 20% of the land was designated for export crop plantations, in practice, a significantly larger portion was utilized (some sources suggest it approached 100%). This left native populations with limited land for planting food crops, resulting in famine in various regions, and in some instances, peasants were required to work more than the stipulated 60 days.

This policy brought substantial wealth to the Dutch through export growth, averaging around 14%. It not only averted Dutch bankruptcy but also rapidly made the Dutch East Indies financially self-sufficient and highly profitable. As early as 1831, this approach allowed for a balanced budget in the Dutch East Indies, and surplus revenues were used to pay off debts from the defunct VOC regime.

However, the cultivation system was associated with famines and epidemics in the 1840s, initially in Cirebon and then in Central Java, primarily because cash crops like indigo and sugar took precedence over rice production.

As political pressures in the Netherlands, influenced in part by these issues and rent-seeking independent merchants favoring free trade or local preference, mounted, the cultivation system was eventually abolished, giving way to a free-market Liberal Period that promoted private enterprise.

Rail transportation in Indonesia

Indonesia, known as the Dutch East Indies during this period, became the second Asian country to establish a rail transport system, following India. China and Japan would soon follow suit. The inception of Indonesia’s railway system dates back to June 7, 1864, when Governor General Baron Sloet van den Beele initiated the first railway line in Kemijen village, Semarang, Central Java.

The railway commenced operations on August 10, 1867, in Central Java, connecting the newly constructed Semarang station to Tanggung over a 25-kilometer route. By May 21, 1873, the railway had expanded to Solo, also located in Central Java, and later extended to Yogyakarta. This initial line was operated by a private company called Nederlandsch-Indische Spoorweg Maatschappij (NIS or NISM) and adhered to the standard gauge of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in). Subsequent railway construction, undertaken by both private and state railway companies, adopted the 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge.

During this era, the Dutch government displayed reluctance in constructing its own railway lines, favoring a policy that allowed private enterprises significant freedom in railway development.

The Liberal Period

The Cultivation System inflicted significant economic hardship on Javanese peasants, leading to famine and epidemics during the 1840s, which garnered widespread criticism in the Netherlands.

Before the late 19th-century economic downturn, the dominant policy-making force in the Netherlands had been the Liberal Party. Its commitment to a free-market philosophy extended to the Dutch East Indies, where the cultivation system was deregulated. Starting in 1870, agrarian reforms marked a significant shift as producers were no longer compelled to supply crops for export. Instead, the Dutch East Indies were opened up to private enterprise. Dutch entrepreneurs established large and profitable plantations. Between 1870 and 1885, sugar production doubled, and new crops like tea and cinchona flourished, while rubber cultivation was introduced, resulting in substantial Dutch profits.

These changes were not confined to Java or agriculture. Sumatra and Kalimantan became valuable sources of oil for industrializing Europe. Frontier plantations for tobacco and rubber led to deforestation in the Outer Islands. Dutch commercial interests expanded beyond Java to the outer islands, gradually bringing more territory under direct Dutch government control or dominance in the latter half of the 19th century. Tens of thousands of laborers, often referred to as coolies, were brought from China, India, and Java to work on these plantations, enduring harsh treatment and a high mortality rate.

Liberals argued that the benefits of this economic expansion would eventually benefit the local population. However, the resulting scarcity of land for rice production, combined with rapidly increasing populations, particularly in Java, led to further hardships. The global recession of the late 1880s and early 1890s caused a collapse in commodity prices upon which the Dutch East Indies depended. Journalists and civil servants observed that a significant portion of the Indonesian population fared no better than they had under the previous regulated Cultivation System economy, and tens of thousands suffered from starvation.

The Aceh War

The Aceh War emerged as an armed military confrontation between the Sultanate of Aceh and the Kingdom of the Netherlands, sparked by negotiations between Aceh representatives and the United States in Singapore in early 1873. This conflict was a component of a series of late 19th-century clashes that solidified Dutch dominance over what is now Indonesia. The campaign stirred controversy in the Netherlands, with reports of a significant death toll and photographic evidence.

Isolated and bl*ody insurgencies persisted as late as 1914, while less v!olent forms of Acehnese resistance endured until the era of World War II and the Japanese occupation.

Dutch Involvement in Bali

In 1906, Dutch forces conducted a military operation in Bali, which was a part of their colonial efforts to suppress resistance. This intervention resulted in the tragic loss of over 1,000 lives, predominantly civilians. The campaign targeted and eliminated the Balinese rulers of Badung and their families, while also devastating the southern Bali kingdoms of Badung and Tabanan and weakening the Klungkung kingdom. Remarkably, this marked the sixth instance of Dutch military intervention in Bali.

THE RISE OF INDONESIA

Budi Utomo

Budi Utomo is recognized as the earliest nationalist society in the Dutch East Indies. Founded by Wahidin Soerdirohoesodo, a retired government doctor, Budi Utomo aimed to harness the potential of native intellectuals for the betterment of public welfare through education and culture.

Initially, Budi Utomo’s focus was not political, but over time, its objectives gradually shifted towards political matters, including representation in the conservative Volksraad (the People’s Council) and provincial councils in Java. Budi Utomo officially disbanded in 1935, with some of its members joining the prominent political party of that era, the moderate Greater Indonesian Party (Parindra).

The use of Budi Utomo as a marker for the emergence of modern nationalism in Indonesia is a subject of debate. While many scholars concur that Budi Utomo was likely the first modern indigenous political organization, others question its significance as an indicator of Indonesian nationalism.

Muhammadiyah

On November 18, 1912, Ahmad Dahlan, a court official at the kraton of Yogyakarta and a well-educated Muslim scholar who had studied in Mecca, founded Muhammadiyah in Yogyakarta. Several compelling factors underpinned the establishment of this movement. Notably, these included the perceived societal stagnation among Muslims and the increasing influence of Christianity.

Ahmad Dahlan, deeply influenced by Egyptian reformist Muhammad Abduh, believed that the modernization and purification of religion, free from syncretic practices, were crucial for the reform of Islam. Therefore, from its inception, Muhammadiyah has been strongly committed to upholding the concept of tawhid (monotheism) and the refinement of monotheistic beliefs within society.

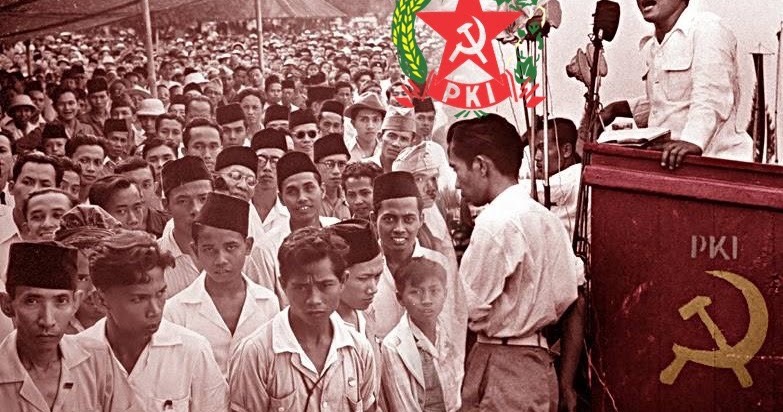

The Communist Party Of Indonesia

In 1914, the Indies Social Democratic Association (ISDV) was founded by Dutch socialist Henk Sneevliet in collaboration with another socialist from the Dutch East Indies. This organization, comprised of 85 members, marked a merger between two Dutch socialist parties, the SDAP and the Socialist Party of the Netherlands. Eventually, this would evolve into the Communist Party of the Netherlands under the leadership of Dutch East Indies representatives. The Dutch members of the ISDV introduced communist ideologies to educated Indonesians seeking avenues to challenge colonial rule.

Subsequently, the ISDV found inspiration in the October Revolution in Russia, envisioning a similar uprising in Indonesia. The organization gained momentum, particularly among Dutch settlers in the archipelago. The formation of Red Guards, totaling 3,000 members in just three months, was a significant development. In late 1917, there was a revolt by soldiers and sailors at the Surabaya naval base, which led to the establishment of soviets. Colonial authorities responded by suppressing the Surabaya soviets and dismantling the ISDV, resulting in the deportation of its Dutch leaders, including Sneevliet, back to the Netherlands.

Around the same period, ISDV and sympathizers with communist ideologies began infiltrating other political groups in the Dutch East Indies, employing a tactic known as the “block within” strategy. The most noticeable impact was the infiltration of the nationalist-religious organization Sarekat Islam (Islamic Union), which advocated a pan-Islamic stance and freedom from colonial rule. Several members, including Semaun and Darsono, were influenced by radical leftist ideas. Consequently, communist ideas and ISDV agents were effectively embedded within the largest Islamic organization in Indonesia. As a result of the involuntary departure of various Dutch cadres, coupled with these infiltration efforts, the composition of the membership shifted from being predominantly Dutch to predominantly Indonesian.

Nahdlatul Ulama

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) is a prominent Islamic organization in Indonesia. Its membership has been estimated to range from 40 million in 2013 to over 95 million in 2021, solidifying its position as the largest Islamic organization globally. NU serves as a charitable institution, supporting educational institutions and healthcare facilities, while also mobilizing communities to combat poverty.

Established in 1926 by religious scholars and merchants, NU’s primary objectives are to uphold traditional Islamic practices, particularly those aligned with the Shafi’i school of thought, and safeguard the economic interests of its members. NU’s religious perspectives are often described as “traditionalist,” emphasizing the coexistence of local culture with Islamic principles, as long as they do not contradict the teachings of Islam. In contrast, Indonesia’s second-largest Islamic organization, Muhammadiyah, is seen as “reformist” for its more literal interpretation of the Quran and Sunnah.

Some leaders within Nahdlatul Ulama ardently support Islam Nusantara, a unique form of Islam that has evolved through interaction, contextualization, indigenization, interpretation, and adaptation to Indonesia’s socio-cultural context. Islam Nusantara promotes moderation, opposes fundamentalism, advocates pluralism, and, to some extent, embraces syncretism. However, it’s important to note that many NU elders, leaders, and religious scholars opt for a more conservative approach and reject the principles of Islam Nusantara.

The period when Japan occupied the Dutch East Indies.

During World War II, the Empire of Japan occupied the Dutch East Indies, which is now Indonesia, from March 1942 until September 1945, marking a pivotal period in Indonesian history. The occupation was prompted by the Netherlands falling under German occupation in May 1940, leading to martial law being declared in the Dutch East Indies. Failed negotiations between the Dutch authorities and the Japanese resulted in the freezing of Japanese assets in the archipelago.

The Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies commenced on January 10, 1942, and within three months, the Imperial Japanese Army had taken control of the entire colony, with the Dutch surrendering on March 8. Initially, many Indonesians welcomed the Japanese as liberators from Dutch colonial rule, but sentiment shifted as millions of Indonesians were conscripted as forced laborers (romusha) for various development and defense projects in Java, and hundreds of thousands were sent to distant locations, including Burma and Siam.

During 1944-1945, Allied forces largely bypassed the Dutch East Indies, leaving most of the territory under Japanese occupation at the time of Japan’s surrender in August 1945. This occupation marked a significant challenge to Dutch colonial rule and led to numerous extraordinary changes that set the stage for the subsequent Indonesian National Revolution. Unlike the Dutch, the Japanese facilitated the political awakening of Indonesians at the local level, providing education, training, and arms to young Indonesians and giving nationalist leaders a political platform. Consequently, the Japanese occupation laid the groundwork for the declaration of Indonesian independence shortly after Japan’s surrender in the Pacific.

The Indonesian National Revolution

The Indonesian National Revolution encompassed both armed conflict and diplomatic negotiations between the Republic of Indonesia and the Dutch Empire, accompanied by a concurrent internal social revolution in postwar and postcolonial Indonesia. This period extended from Indonesia’s declaration of independence in 1945 to the transfer of sovereignty over the Dutch East Indies from the Netherlands to the Republic of the United States of Indonesia by the close of 1949.

This four-year struggle included sporadic yet fierce armed confrontations, internal political and social upheavals within Indonesia, and two significant international diplomatic interventions. Dutch military forces, supported for a time by World War II allies, were able to maintain control over major urban centers, cities, and industrial assets in the Republican strongholds of Java and Sumatra. However, they struggled to exert authority over the rural areas. By 1949, mounting international pressure on the Netherlands, with the United States threatening to cease economic aid for post-World War II reconstruction, combined with a military stalemate, led to the transfer of sovereignty over the Dutch East Indies to the Republic of the United States of Indonesia.

This revolution marked the conclusion of Dutch colonial rule in the East Indies, excluding New Guinea. It brought about significant changes in societal hierarchies and reduced the authority of local rulers (raja). Despite these transformations, the revolution did not substantially improve the economic or political prospects of the majority of the population, though a select few Indonesians gained more prominent roles in commerce.

The Liberal Democratic Period

The era of Liberal Democracy in Indonesia was a significant chapter in the nation’s political history. It commenced on August 17, 1950, shortly after the dissolution of the federal United States of Indonesia, and concluded with the imposition of martial law and President Sukarno’s decree on July 5, 1959, ushering in the Guided Democracy period.

This period followed over four years of intense conflict during the Indonesian National Revolution, culminating in the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference and the transfer of sovereignty to the United States of Indonesia (RIS). Nevertheless, the RIS government faced internal divisions and opposition from many republicans.

On August 17, 1950, the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (RIS) was officially dissolved, transitioning to a parliamentary democracy based on the Provisional Constitution of 1950. However, Indonesia experienced growing societal divisions driven by regional disparities in customs, morals, tradition, religion, the influence of Christianity and Marxism, and concerns about Javanese political dominance.

The nation grappled with poverty, low education levels, and authoritarian traditions, along with the emergence of separatist movements like Darul Islam, which sought an “Islamic State of Indonesia,” and rebels in regions such as Maluku, Sulawesi, and West Sumatra.

The economy was in disarray due to Japanese occupation and subsequent conflict with the Dutch, compounded by the government’s lack of experience. Illiteracy, unskilled labor, and a lack of management expertise were widespread. Inflation, smuggling, and the destruction of plantations during the occupation and war further strained the nation.

The Liberal Democracy era was marked by the proliferation of political parties and the establishment of a parliamentary system. It witnessed Indonesia’s first genuinely free and fair elections, although this period was also characterized by considerable political instability, with frequent changes of government.

Guided Democracy

The period of liberal democracy in Indonesia, which spanned from the re-establishment of a unitary republic in 1950 until the declaration of martial law in 1957, witnessed the emergence and subsequent fall of six cabinets, with the most enduring lasting just under two years. Even the inaugural national elections in 1955 failed to bring about political stability.

Guided Democracy, in place in Indonesia from 1959 until the onset of the New Order in 1966, was conceived by President Sukarno as an attempt to instill political stability. Sukarno was dissatisfied with the parliamentary system implemented during the liberal democracy era, given the divisive political climate. He aimed to establish a system based on the traditional village model of discussion and consensus, guided by village elders. With the declaration of martial law and the introduction of this system, Indonesia reverted to a presidential system, with Sukarno resuming his role as the head of government.

Sukarno proposed a tripartite blend of nationalism, religion, and communism into a cooperative Nas-A-Kom or Nasakom governance concept. The intention was to appease the four primary political factions in Indonesia: the military, secular nationalists, Islamic groups, and the communists. With the backing of the military, he instituted Guided Democracy in 1959 and suggested a cabinet inclusive of all major political parties, including the Communist Party of Indonesia, though the latter never actually assumed functional cabinet positions.

The New Order

The 30th September Movement

Starting in the late 1950s, President Sukarno found himself in a delicate position, tasked with balancing the increasingly antagonistic forces of the army and the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). His “anti-imperialist” ideology led Indonesia to become more reliant on the Soviet Union and, notably, China. As of 1965, during the height of the Cold War, the PKI had deeply infiltrated all levels of government. With Sukarno’s support and the backing of the air force, the PKI gained influence at the expense of the army, thereby intensifying the enmity between the two.

By the late 1965, the army was divided into a left-wing faction aligned with the PKI and a right-wing faction courted by the United States, which sought Indonesian allies in its Cold War confrontation with the Soviet Union. This division was fostered by exchanges and arms deals orchestrated by the United States and other nations, further deepening the rift within the military.

The Thirtieth of September Movement, a self-declared organization comprising members of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, orchestrated an unsuccessful coup d’état in the early hours of October 1, 1965, during which six Indonesian Army generals were assassinated. Following the coup attempt, the organization claimed control over media and communication outlets and took President Sukarno under its protection. However, the coup failed in Jakarta by the end of the day. Simultaneously, an effort was made in central Java to seize control of an army division and several cities, resulting in the death of two more senior officers before the rebellion was quelled.

The 1965 Indonesian Mass K!llings

From 1965 to 1966, Indonesia experienced large-scale k!llings and civil unrest primarily aimed at members of the Communist Party (PKI) and various other groups, including communist sympathizers, Gerwani women, ethnic Chinese, atheists, alleged “unbelievers,” and supposed leftists. During the main period of v!olence from October 1965 to March 1966, it is estimated that between 500,000 to 1,000,000 people lost their lives. These atrocities were orchestrated by the Indonesian Army under Suharto, with evidence suggesting support from foreign countries like the United States and the United Kingdom.

This wave of v!olence originated as an anti-communist purge in response to a contentious attempted coup d’état by the 30 September Movement. Widely reported estimates suggest that at least 500,000 to 1.2 million individuals perished, with some projections going as high as two to three million. This purge was a pivotal moment in the transition to the “New Order” and the dismantling of the PKI as a political force, influencing the global Cold War dynamics. These upheavals led to the downfall of President Sukarno and the commencement of Suharto’s authoritarian presidency, which would last for three decades.

The failed coup attempt unleashed long-standing communal an!mosities within Indonesia, which were further exacerbated by the Indonesian Army’s swift attribution of blame to the PKI. Furthermore, intelligence agencies from the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia engaged in disinformation campaigns against Indonesian communists. During the Cold War, the United States and its Western allies were motivated by the objective of halting the spread of communism and expanding Western Bloc influence. Britain had an additional incentive for wanting to remove Sukarno due to his government’s involvement in a covert conflict with the neighboring Federation of Malaya.

The purge resulted in the expulsion of communists from political, social, and military spheres, with the PKI being disbanded and outlawed. Mass k!llings began in October 1965, soon after the coup attempt, reaching their peak over the following year before gradually subsiding in early 1966. These atrocities initiated in the capital, Jakarta, and later spread to Central and East Java, and eventually Bali. Thousands of local vigilante groups and Army units were involved in the k!lling of both confirmed and suspected PKI members. These events occurred nationwide, with the most intense incidents concentrated in PKI strongholds like Central Java, East Java, Bali, and northern Sumatra.

By March 1967, Indonesia’s provisional parliament stripped Sukarno of his remaining authority, naming Suharto as Acting President. In March 1968, Suharto was formally elected president.

Despite a shared consensus at the highest levels of the U.S. and British governments that it was necessary “to liquidate Sukarno,” as revealed in a 1962 CIA memorandum, and the existence of extensive contacts between anti-communist army officers and the U.S. military establishment, the CIA denied active involvement in the k!llings. However, declassified U.S. documents in 2017 unveiled that the U.S. government had extensive knowledge of the mass k!llings from the outset and supported the actions of the Indonesian Army. U.S. complicity in the k!llings, including providing extensive lists of PKI officials to Indonesian death squads, had been previously established by historians and journalists.

A highly classified CIA report from 1968 asserted that these massacres “rank as one of the worst mass m*rders of the 20th century, along with the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the Nazi mass m*rders during the Second World War, and the Maoist blo•*odbath of the early 1950s.”

The Transition into the New Order

The term “New Order” was coined by Indonesia’s second President, Suharto, to define his leadership from 1966 until his resignation in 1998. Suharto used this label to distinguish his presidency from that of his predecessor, Sukarno.

In the aftermath of the 1965 attempted coup, Indonesia faced a precarious political landscape. Suharto’s New Order garnered substantial support from those seeking a departure from the issues plaguing the nation since its independence. The “generation of ’66” symbolized a new wave of youthful leaders and fresh intellectual thinking. Following Indonesia’s period of communal and political strife, along with economic turmoil and societal disarray from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, the “New Order” aimed to establish and maintain political stability, foster economic development, and reduce widespread involvement in the political process. Key elements of the “New Order” established in the late 1960s included a prominent military role in politics, the institutionalization and commercialization of political and social groups, and the selective yet harsh suppression of dissent. A strong stance against communism, socialism, and Islamist ideologies remained a defining characteristic of the presidency for the next three decades.

However, within a few years, many of its initial supporters became disinterested or opposed to the New Order, which was essentially a military-backed faction with limited civilian backing. Among those in the pro-democracy movement that compelled Suharto to step down during the 1998 Indonesian Revolution and subsequently assumed power, the term “New Order” is now used pejoratively. It is often employed to describe individuals associated with the Suharto era or those who continued the practices of his authoritarian regime, such as corruption, collusion, and nepotism.

The Indonesian Invasion Of East Timor

East Timor’s unique territorial distinction from the rest of Timor and the Indonesian archipelago results from its history as a Portuguese colony, as opposed to Dutch colonial rule. An agreement dividing the island between these two colonial powers was established in 1915. During World War II, East Timor experienced Japanese occupation, leading to the emergence of a resistance movement that tragically claimed the lives of 60,000 people, constituting 13 percent of the population at the time. After the war, the Dutch East Indies gained independence as the Republic of Indonesia, while the Portuguese resumed their control over East Timor.

In 1974, Indonesian nationalists and military hardliners, particularly figures within the intelligence agency Kopkamtib and the special operations unit Opsus, viewed the Portuguese coup as an opportunity for the annexation of East Timor by Indonesia. Major General Ali Murtopo, the head of Opsus and a close adviser to Indonesian President Suharto, along with his protege Brigadier General Benny Murdani, directed military intelligence operations and spearheaded the Indonesian push for annexation.

The Indonesian invasion of East Timor commenced on December 7, 1975, when the Indonesian military (ABRI/TNI) entered East Timor under the pretext of opposing colonialism and communism, with the goal of overthrowing the emerging Fretilin regime of 1974. The removal of the popular, albeit brief, Fretilin-led government triggered a violent occupation that persisted for a quarter-century, resulting in the estimated loss of approximately 100,000 to 180,000 lives, including both soldiers and civilians who were killed or succumbed to starvation.

The Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation in East Timor documented a minimum estimate of 102,000 conflict-related deaths in East Timor from 1974 to 1999, encompassing 18,600 violent killings and 84,200 deaths due to disease and starvation. Indonesian forces and their auxiliaries were responsible for 70% of these killings.

In the initial months of the occupation, the Indonesian military faced fierce resistance from insurgents in the mountainous interior of the island. However, from 1977 to 1978, the military acquired advanced weaponry from the United States and other nations to dismantle Fretilin’s framework. The final two decades of the century were marked by persistent confrontations between Indonesian and East Timorese factions over East Timor’s status. In 1999, the majority of East Timorese voted decisively for independence, rejecting the alternative option of “special autonomy” while remaining part of Indonesia. Following two and a half years of transition facilitated by various United Nations missions, East Timor finally achieved independence on May 20, 2002.

The Free Aceh Movement

The Free Aceh Movement was a separatist organization that aimed for the independence of the Aceh region in Sumatra, Indonesia. From 1976 to 2005, GAM engaged in an insurgency against Indonesian government forces, resulting in a tragic loss of over 15,000 lives. In 2005, following a peace agreement with the Indonesian government, the organization abandoned its separatist aspirations and disbanded its armed wing. Subsequently, it transformed into the Aceh Transition Committee.

Jemaah Islamiyah’s Establishment

Jemaah Islamiyah, a Southeast Asian Islamist militant organization rooted in Indonesia, is committed to establishing an Islamic state in Southeast Asia. Following the Bali bombing attributed to JI, the UN Security Council Resolution 1267 designated it as a terrorist group associated with Al-Qaeda or the Taliban on October 25, 2002.

JI operates transnationally, with cells in Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Besides its links to Al-Qaeda, it’s believed to have connections with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and Jamaah Ansharut Tauhid, a splinter group formed by Abu Bakar Baasyir in 2008. The United Nations, Australia, Canada, China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States have designated JI as a terror!st organization.

On November 16, 2021, the Indonesian National Police uncovered that JI had been operating covertly under the guise of a political party, the Indonesian People’s Da’wah Party. This revelation shocked many as it marked the first instance in Indonesia where a terror!st organization masqueraded as a political party, attempting to interfere in the country’s political system.

THE REFORM ERA

The 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake

Indonesia bore the initial brunt of the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, which struck on December 26, 2004. The disaster inundated the northern and western coastal regions of Sumatra, as well as the smaller outlying islands surrounding Sumatra. The province of Aceh suffered the most extensive loss of life and destruction. The tsunami surged ashore within 15 to 30 minutes following the catastrophic earthquake. By April 7, 2005, the estimated count of missing individuals was lowered by over 50,000, resulting in a final toll of 167,540 individuals lost or unaccounted for.

Joko Widodo

Jokowi hails from a riverside slum in Surakarta, where he was born and raised. He completed his education at Gadjah Mada University in 1985 and tied the knot with his wife, Iriana, a year later. Prior to becoming mayor of Surakarta in 2005, he earned his living as a carpenter and engaged in furniture exporting.

His tenure as mayor brought him national recognition, leading to his election as Jakarta’s governor in 2012, with Basuki Tjahaja Purnama as his deputy. While governing Jakarta, he revitalized local politics, introduced high-profile unannounced spot checks (blusukan visits), streamlined the city’s bureaucracy, and made significant strides in reducing corruption. Jokowi also implemented long-awaited programs to enhance the quality of life, including universal healthcare, river dredging to mitigate flooding, and the commencement of the city’s subway system construction.

In 2014, he secured the PDI-P nomination for that year’s presidential election, selecting Jusuf Kalla as his running mate. Jokowi emerged victorious against his opponent, Prabowo Subianto, despite election disputes, and he assumed office on October 20, 2014. During his presidency, he concentrated on economic growth, infrastructure development, and an ambitious health and education agenda. In foreign policy, his administration prioritized “protecting Indonesia’s sovereignty,” sinking illegal foreign fishing vessels, and maintaining a strict stance on capital punishment for drug smugglers, despite intense objections from foreign powers like Australia and France.

He secured re-election in 2019 for a second five-year term, once again defeating Prabowo Subianto.