To the ancient Romans, the universe was filled with divine beings, ranging from well-known gods like Jupiter, the god of thunder, Mars, the god of war, and Venus, the goddess of love, to lesser-known deities overseeing every aspect of nature. Even inanimate objects such as trees, rivers, and door hinges were thought to be under the protection of their own gods and goddesses. Here are ten such deities you might consider honoring with a prayer.

10. Mutunus Tutunus

The first scholars to investigate the ruins of the Roman city of Pompeii were shocked by many of the objects they found. Expecting a dignified landscape adorned with elegant statues, they instead encountered numerous images and carvings of large phalluses almost everywhere they looked. The cult of the penis was unmistakable.

While the Greek god Priapus is well-known and popular on the internet for his depictions with an absurdly large phallus, the Romans also admired him. However, there was an earlier Roman god, Mutunus Tutunus, who was even more explicitly phallic. Some sources suggest that Mutunus Tutunus was represented solely by an enormous penis, with no body attached.

The temple dedicated to Mutunus Tutunus was located on the Velian Hill and is believed to be among the oldest religious practices in Rome. However, specific details about the worship methods are limited. Christian authors, who found the concept of penile worship repulsive, described the rituals in vivid terms. They alleged that on the eve of her marriage, a bride would visit the temple and sit astride the god’s phallus, symbolically losing her virginity to the statue. This act was likely intended to invoke fertility for the upcoming marriage.

9. Lares

In ancient Rome, each family had guardian deities called Lares, responsible for protecting the household and its members. These divine protectors were typically represented by small figurines made of bronze or clay, which were kept in a dedicated shrine within the home. Families would offer sacrifices to the Lares, and during meals, it was customary to place these statues at the table, symbolizing their constant vigilance over the family’s well-being.

The origins of the Lares are obscure, possibly tracing back to the earliest days of Roman civilization. Some theories suggest that the Lares evolved from ancestor worship, a practice where deceased family members were buried within the home to watch over the living. When Roman law later prohibited such burials, the Lares assumed the role of these ancestral spirits.

The veneration of the Lares was intended to prevent the extinction of the family line. When families moved to a new residence, they would take their Lares’ statues with them to ensure the continued protective presence in their new home.

The Lares were thought to significantly influence the daily lives of Roman families. According to one legend, Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome, was born under remarkable circumstances. While tending to the hearth, his mother saw a phallus emerge from the embers, which impregnated her. This phallus was believed to be associated with a Lares, indicating that these household gods could directly affect the lineage of Roman royalty.

8. Liber

Liber was a deity highly revered by Rome’s commoners, representing freedom, wine, and male fertility. During periods of oppressive aristocratic rule, the oppressed turned to Liber as a symbol of their right to resist the Senate’s commands. The Liberalia festival, a major event on the Roman calendar, was enthusiastically celebrated by the less fortunate.

It included a grand procession featuring a large phallus, accompanied by lively and irreverent songs, which culminated in the phallus being adorned with an ivy wreath. Liber’s influence extended beyond human fertility to the fertility of the earth itself. Over time, Libera, Liber’s female counterpart, was also honored during the Liberalia to invoke fertility for women.

In ancient Rome, young boys wore a protective amulet called a bulla around their necks to shield them from malevolent supernatural forces. Upon reaching adulthood and putting on their first toga, these boys would ceremoniously remove the bulla and present it at an altar during the Liberalia festival.

7. Mefitis

Roman deities covered a diverse array of attributes, many of which were unrelated to sexuality. For example, Mefitis was worshipped as the deity of harmful vapors rather than sexual health. She symbolized the dangerous gases from underground caverns and marshlands, believed to be sources of disease.

The ancient idea of miasma connected foul odors with illness, a concept partially valid as decaying organic matter and polluted environments can harbor pathogens. As a result, the Romans invoked Mefitis for protection against the harmful effects of these noxious fumes.

Initially, Mefitis may have been revered as a benevolent goddess associated with healing springs, often marked by a strong sulfur smell. Over time, she also became linked to these sulfuric odors. In areas with particularly strong smells, shrines were dedicated to Mefitis. In Rome, such shrines were found in places known for fevers and misfortune.

The discovery of numerous artifacts dedicated to Mefitis suggests her widespread appeal. In certain Italian regions, volcanic gases emerge from the earth, posing a lethal threat to animals that come too close. It is believed that offerings to Mefitis involved driving animals into these dangerous areas as a form of sacrifice.

6. Annona

In the early years of the Roman Empire, Rome was Europe’s most populous city, with an estimated one million inhabitants. The city’s survival depended on a continuous supply of food, as any disruption could lead to famine. Bread shortages often triggered riots. Juvenal famously remarked that the contentment of Romans was maintained through “bread and circuses.”

Emperors ensured Rome’s food supply by securing grain imports from Egypt, often at subsidized rates. To honor their crucial role in feeding the city, emperors personified the grain supply as the deity Annona, thereby giving their duty to nourish the people a divine significance.

Annona, the personification of Rome’s grain supply, often appeared on currency. She is shown holding a sheaf of grain in one hand and a cornucopia in the other, symbolizing abundance. Sometimes, she is depicted with a ship’s bow, signifying her blessing on the vessels that brought provisions to the city.

5. Summanus

The Roman pantheon was extensive, making it difficult to remember all the deities. Ovid referenced a temple in Rome dedicated to the mysterious god Summanus, whose identity he did not know. We now know that Summanus was the god of night-time lightning.

In ancient times, lightning was viewed as a powerful and mysterious act of the gods, primarily associated with Jupiter, who wielded thunderbolts against wrongdoers. Pliny the Elder noted that there were up to nine deities governing different aspects of lightning, with Summanus specifically overseeing nocturnal lightning strikes.

There are signs that Summanus was sometimes considered nearly equal in status to Jupiter. This is indicated by the construction of a temple for Summanus after a lightning strike decapitated a statue of Jupiter. Moreover, when a sacred grove was struck by lightning, sacrifices were made to Jupiter, but an identical number and type of black animals were also offered to Summanus.

4. Verminus

In the second century BC, a prominent family in Rome established an altar dedicated to the deity Verminus. Discovered in the 19th century, Verminus was a largely unknown figure with no previous records of worship.

His name suggests he presided over pests and vermin that afflicted agriculture and livestock. As a divine protector against such infestations, Verminus would have been frequently invoked by agrarian Romans to protect their crops and animals from diseases that could lead to food shortages and famine.

Recent studies suggest that the altar dedicated to Verminus may have been erected in response to an epidemic, likely involving worms, that was affecting both animals and humans in Rome at that time.

3. Laverna

Horace, the Roman poet, described a character known for his integrity who would openly invoke Apollo or Janus during sacrifices. However, in a whisper, he would secretly pray to Laverna, the goddess of trickery, saying:

“Good Laverna, hear my plea,

Help me deceive; let them see me as honest,

Let my deceit be hidden from the crowd,

And let my lies and forgeries remain obscure.”

Laverna, the goddess of thievery and nocturnal misdeeds, was also invoked by individuals who wanted to appear respectable while engaging in deceit. Although she is associated with secrecy and vice, little is known about her. An altar dedicated to her was located near a Roman gate, possibly serving as a discreet support for those involved in illicit activities.

2. The Emperors

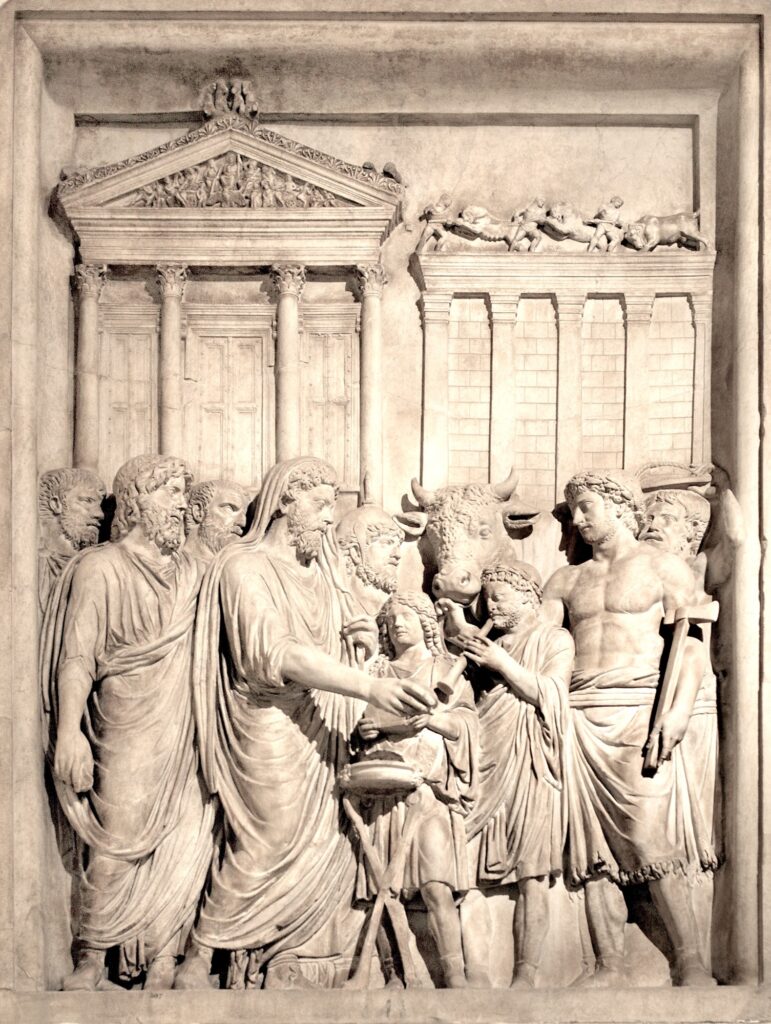

In ancient times, the line between mortals and deities was much more blurred than it is today. It was common for individuals to be deified if they received significant veneration. For the imperial family and their close associates, deification was almost guaranteed. The Roman Imperial cult traces back to the city’s founding, with early heroes and founders often revered as both historical figures and divine offspring.

After their deaths, they were worshipped as gods. Julius Caesar claimed descent from Venus, and after his assassination, his heir Augustus ensured Caesar’s deification, conveniently positioning Augustus as “the son of a god.” Upon Augustus’s death, he was also declared divine.

The practice of deifying emperors after their deaths became customary. Emperor Vespasian, while gravely ill, wittily told his companions that he was about to become a god. However, not all emperors were satisfied with posthumous worship; Caligula, known for his erratic behavior, sought to be acknowledged as a god during his lifetime.

1. Cloacina

The Romans acknowledged the vulnerability of humans while using the toilet, which might explain their reverence for Cloacina, the goddess associated with the Cloaca Maxima, Rome’s main sewer system. Cloacina wasn’t exactly a sanitation deity; rather, her name was linked to the grand sewer known as the Cloaca Maxima or “Greatest Sewer.”

This engineering marvel, which efficiently directed the city’s waste and floodwaters into the River Tiber, was a source of pride for the Roman state. The Romans held the Cloaca Maxima in high regard; even the historian Livy considered it unmatched in his time. To protect this essential infrastructure, a shrine was dedicated to Cloacina.

Classical writers in later periods often adorned their lavatories with verses honoring Cloacina. Jonathan Swift wrote a poem for a friend’s bathroom:

“Here, kind goddess Cloacina,

Receives all tributes at your altar.

In separate rooms, the males and females

Kneel here and pledge their devotion.”