Marie Curie’s remarkable career was defined by a series of groundbreaking achievements. She was a true trailblazer in the field of science, and her contributions to the study of radioactivity and the discovery of new elements continue to inspire researchers today.

Among her many firsts, Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win the prize twice, and the only woman to win two Nobel Prizes in different science fields, including Physics and Chemistry. She and her husband, Pierre Curie, were also the first couple to win a Nobel Prize together.

In addition to her achievements as a researcher, Marie Curie was also a trailblazer in academia. She was the first female professor at the University of Paris, and her groundbreaking research on radioactivity helped to pave the way for future generations of scientists.

Marie Curie’s most famous discoveries include the elements thorium, polonium, and radium, which have had a profound impact on the field of medicine. Her work in this area contributed to the discovery of the cure for cancer, and has given many patients and families a second chance at life.

Have you ever wondered how a woman from a humble background managed to break through gender barriers, shatter stereotypes, and pave the way for other women in a male-dominated field? This article aims to explore the fascinating journey of one such remarkable woman: Marie Curie.

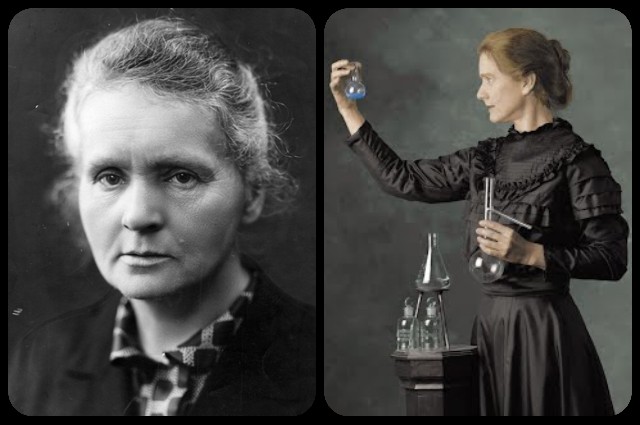

Marie Curie, born Marya Skłodowska in Warsaw, Congress Poland, in the Russian Empire on November 7, 1867, was the youngest of five children in a family of Polish parents. Her parents were both teachers, but the family lived in poverty, having lost their properties during the uprisings for Poland’s independence.

Marie’s father, Władysław Skłodowski, was a physics and mathematics teacher who brought home laboratory equipment after the removal of laboratories in Polish schools during the uprisings. It was here that Marie’s passion for science was ignited. However, her father eventually lost his job, and the family faced severe financial difficulties. To make ends meet, they turned their home into a boarding house for boys.

Despite these challenges, Marie Curie’s determination and love for science led her to become the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the first female professor at the University of Paris. Her story serves as an inspiration to many, as she overcame gender discrimination and poverty to make significant contributions to the field of science.

At the age of ten, tragedy struck Maria when her mother died of tuberculosis. Soon after, her eldest sister also passed away from typhus, a disease she had contracted from one of the boarders who had stayed in their house. These events deeply affected Maria’s faith and led her to become indifferent to religion. Despite her struggles, she excelled in school and graduated with honors from a gymnastics school. However, she also battled with depression and was sent to live with her father’s relatives on several occasions.

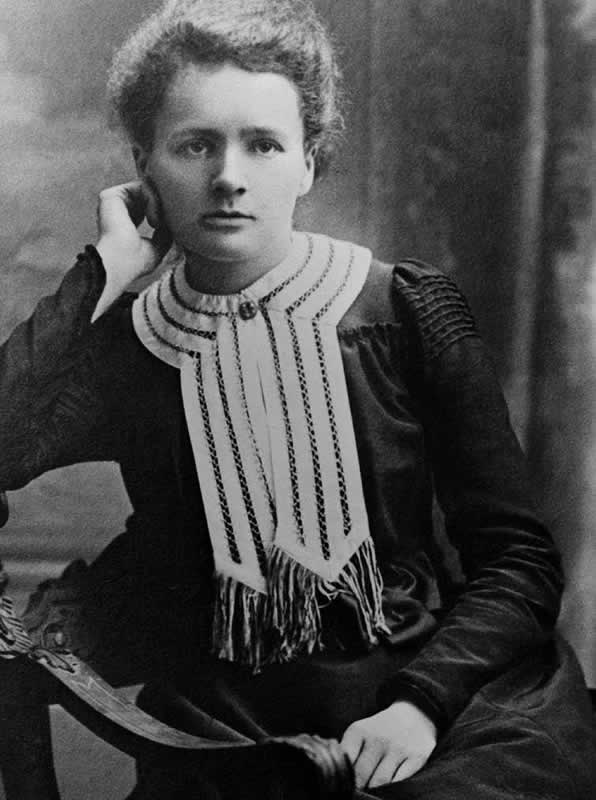

From a young age, Maria had a passion for science and was determined to pursue a career in the field. Unfortunately, at the time, women were not allowed to enroll in regular institutions of higher education. Undeterred, Marie and her older sister, Bronislawa, attended an institution in Poland that admitted female students, called The Flying University. However, they could not afford to attend tuition fees at the same time, so it was agreed that Bronislawa would go first. Despite the challenges, Marie continued to pursue her dreams and eventually became a trailblazing scientist.

To support her sister’s medical studies and receive the same in return two years later, Marie had to take up a job as a home tutor in Warsaw, and later as a governess with a wealthy family, the Żorawskis, who were also her father’s relatives. It was while working for the Żorawskis that she fell in love with their son, Kazimierz. However, the family vehemently opposed their relationship due to Marie’s family’s poverty, and the two were forced to separate.

Heartbroken, Marie continued to work and save money for her education. Her sister, Bronislawa, had married a Polish physician, Kazimierz Dluski, and invited Marie to join them in Paris. However, Marie declined, citing her inability to pay for tuition. Undeterred, Marie worked hard and eventually saved enough money to pursue her dreams of studying science in Paris.

Marie’s thirst for knowledge was unquenchable. Despite financial constraints, she continued to educate herself by reading scientific literature and attending The Flying University while working as a tutor. In 1891, she joined her sister and brother-in-law in Paris but soon moved to an apartment closer to the university campus. She began studying physics, mathematics, and chemistry at the University of Paris and adopted the French version of her name, “Marie.”

Living on a meager income, Marie endured a frugal lifestyle. During the winter season, she wore all her clothes to keep warm and often maintained irregular eating patterns to keep up with her studies. To make ends meet, she tutored in the evenings while attending school in the mornings. In 1893, she earned her certificate in Physics and began working in Gabriel Lippmann’s industrial laboratory. With the help of a fellowship, she continued her studies and obtained her second degree in the following year.

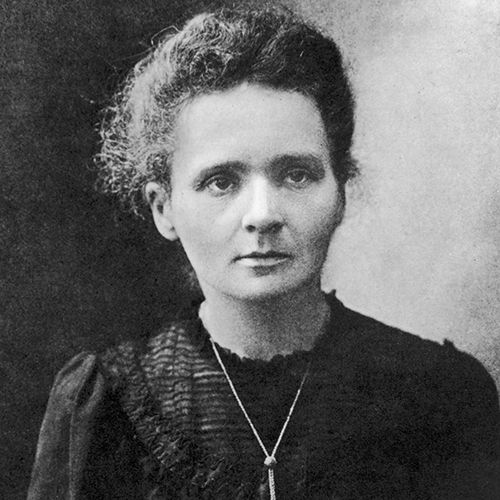

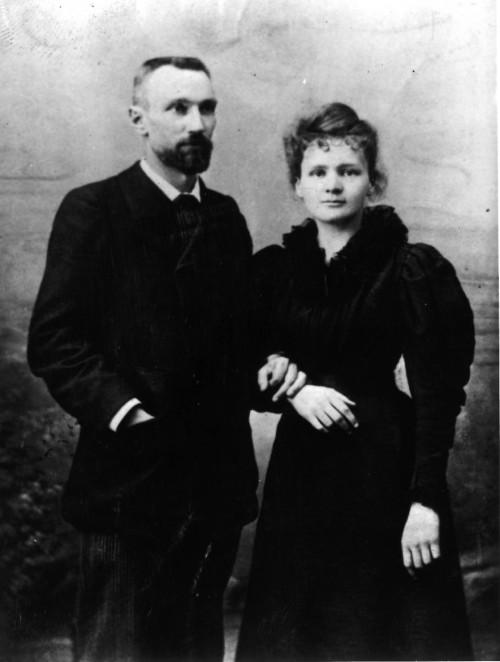

Marie Curie began her career in Paris by investigating the magnetic properties of different types of steel plates. It was during this time that she met Pierre Curie, who was an instructor at the ESPCI Paris, a higher educational institution for physics and chemistry. They shared a mutual interest in natural sciences, which led to a partnership that would later lead them to unprecedented achievements.

Marie’s need for a larger laboratory to conduct her experiments brought her into contact with Pierre. She was introduced to him by Józef Wierusz-Kowalski, a Polish physicist who believed that Pierre could help her gain access to the laboratory space she needed. Eventually, Pierre was able to secure a larger laboratory for Marie, and they began working together.

After being refused a position at Krakow University, Marie Curie was convinced by her future husband Pierre to return to Paris to pursue her PhD degree. Marie had earlier inspired Pierre to conduct research on magnetism which earned him a doctorate degree and a new position as a professor at the University. Pierre and Marie’s relationship soon turned romantic and they got married on July 26, 1895. This gave them the opportunity to not only share their love for each other but also their passion for science on a larger scale. In fact, Marie was once referred to as “Pierre’s biggest discovery”.

After the discovery of X-rays and uranium rays by Wilhelm Röntgen and Henri Becquerel, Marie Curie chose to focus her doctoral thesis on uranium rays. To conduct her research on radiation, Marie used the electrometer, a device that had been invented by Pierre and his brother 15 years earlier. Sadly, Marie’s extensive research on radiation eventually had a detrimental impact on her health and ultimately led to her death. In 1897, the Curies welcomed their first child, Irène, which increased their financial responsibilities. In order to make ends meet, Marie took on a teaching job at a school.

Cc: Nobel Prize

Due to their financial limitations, the couple did not have access to a proper laboratory and had to conduct most of their experiments in a shed near the ESPCI. The shed was poorly ventilated, which led to unknown and heightened levels of radiation exposure. Although the ESPCI did not provide any funding for Marie’s research, she received financial support from various mining companies, organizations, and governments.

Over the course of the next four years, Marie and Pierre published more than 30 papers, either individually or jointly. During this time, they discovered the destructive effects of radium on tumor cells, which is now a core concept used in chemotherapy. Despite their groundbreaking work, Marie faced constant challenges in the male-dominated scientific community. In 1903, the couple was invited by the Royal Institution to present on radioactivity. However, Marie was not allowed to speak because she was a woman. Pierre had to give the speech on her behalf. Moreover, this discrimination nearly cost Marie the Nobel Prize.

The tragedy occurred in 1906 when Pierre Curie was killed in a road accident. Marie was devastated by the loss, but she continued working, taking over her husband’s teaching position at the Sorbonne University. She became the first woman to teach at the university. In 1911, she won her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry for her discovery of radium and polonium. She was the first person to win two Nobel Prizes and the only woman to win in two different fields.

Despite the challenges she faced as a woman in science, Marie continued to make groundbreaking discoveries and pioneered new areas of research. She also established the Radium Institute in Paris, which focused on radiology and cancer treatment. Marie Curie died in 1934 from leukemia, likely caused by her long-term exposure to radiation during her research. Her legacy continues to inspire and empower women in science today.

After the tragic loss of her husband Pierre in a road accident, Marie Curie and her children were left devastated. In the aftermath, the University of Paris offered Marie her husband’s former position as a professor and chair of physics, making her the first female professor at the university. Despite this honor, Marie still faced the challenge of not having a proper laboratory to conduct her research. She even considered leaving the university for the Pasteur Institute. However, the University of Paris and the Pasteur Institute eventually collaborated to build the Curie Pavilion, a radium institute that she led.

Marie Curie faced persistent gender discrimination despite her numerous accomplishments. Detractors labeled her a foreigner and atheist. When she was up for election to the French Academy of Sciences, she was voted down solely because she was a woman, with members stating, “Women cannot be part of the Institute of France.”

A rumored year-long affair with Paul Langevin, a former student of her late husband who was divorced, led to a scandal that threatened to destroy her career. Furious mobs gathered outside her home, forcing her to relocate with her daughters to a friend’s home for safety.

However, despite the opposition and scandal, Marie was awarded a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911 for “her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the elements radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable element.”

Despite facing opposition, Marie Curie remained firm in her resolve to separate her personal life from her scientific work. In 1911, she was diagnosed with a kidney ailment and had to withdraw from the public eye for two years.

Despite her health struggles, Marie Curie continued to make groundbreaking contributions to science. She became the first woman to head a laboratory when she was appointed Director of the Curie Laboratory at the Radium Institute of the University of Paris. During the First World War, she established radiological centers to aid wounded soldiers. With the help of her daughter Iréne and a military doctor, she developed mobile x-ray units for locating fractures and shrapnel in soldiers’ bodies. These units helped over a million soldiers, but Marie and her team received no official recognition from the French government.

Marie Curie’s later years were marked by international recognition of her groundbreaking work. She traveled extensively to different countries, including the United States, Spain, Brazil, Belgium, and Czechoslovakia. During her visit to the United States, donations were made to provide her with a sample of radium for continued research.

The Curie Institute, which she co-founded, became one of the world’s leading research laboratories on radioactivity. The institute produced four more Nobel laureates, including her daughter Irène Joliot-Curie and son-in-law Frédéric Joliot-Curie.

Marie Curie’s legacy lives on, and she has continued to inspire women in science worldwide. She served on various committees, making a tremendous impact wherever she found herself. Her sister, Bronislawa, eventually served as a director at the Warsaw Radium Institute to which Marie had made significant contributions. In 1920, Marie Curie became the first female member of The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, further demonstrating her far-reaching impact on the scientific community.

At the age of 66, Marie Curie passed away on July 4, 1934. She is believed to have died from aplastic anemia, a bone marrow disease that was caused by her prolonged exposure to radiation. Her final resting place was beside her husband at a cemetery in Sceaux.

Almost 60 years after her death, in recognition of their groundbreaking contributions to science, both Marie Curie and her husband’s remains were transferred to the Paris Panthéon, a revered burial ground for France’s most distinguished individuals. Marie Curie became the first woman to be posthumously interred at the Panthéon based on her own merits.

To protect against the radioactivity present in their bodies, their remains were encased in lead lining. Similarly, their papers and journals were preserved in lead-lined boxes and were to be handled only while wearing protective clothing.

Marie Curie’s extraordinary achievements in science and her enduring legacy have been commemorated in various ways. Monuments, paintings, and institutions have been named in her honour, and biographies and movies have been produced about her life. She has even been featured on currencies and postage stamps, and an asteroid has been named after her (7000 Curie).

The unit of radioactivity known as the ‘curie’ was named after Marie Curie and her husband, Pierre. The element ‘curium’ was also named after them, and the radioactive minerals ‘curite,’ ‘sklodowskite,’ and ‘cuprosklodowskite’ were named in their honour as well. In 2011, the United Nations declared the year as “The International Year of Chemistry” in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Marie Curie’s second Nobel Prize.

Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, the only woman to win in two fields, and the only person to win in multiple sciences (Physics and Chemistry). Her contributions to science have left an indelible mark and continue to inspire generations of scientists and researchers to this day.