The concept of the apocalypse has repeatedly surfaced throughout human history, with numerous predictions about when it will occur. While some forecasters offer vague signs and omens, others boldly specify exact dates and times for the world’s end. Despite the consistent failure of these predictions, the fascination with them endures, resulting in numerous forecasts over the centuries. Remarkably, many individuals continue to take these prophecies seriously.

This compilation reviews ten strange predictions of the apocalypse, each specifying an exact time for its occurrence. Naturally, all these predictions have been disproven, as evidenced by our continued existence and your reading of this text. However, it’s possible that a future prediction might be accurate. As the saying goes, “A broken clock is right twice a day.” Perhaps someday, someone will correctly predict the apocalypse at a specific time.

10. AD 400

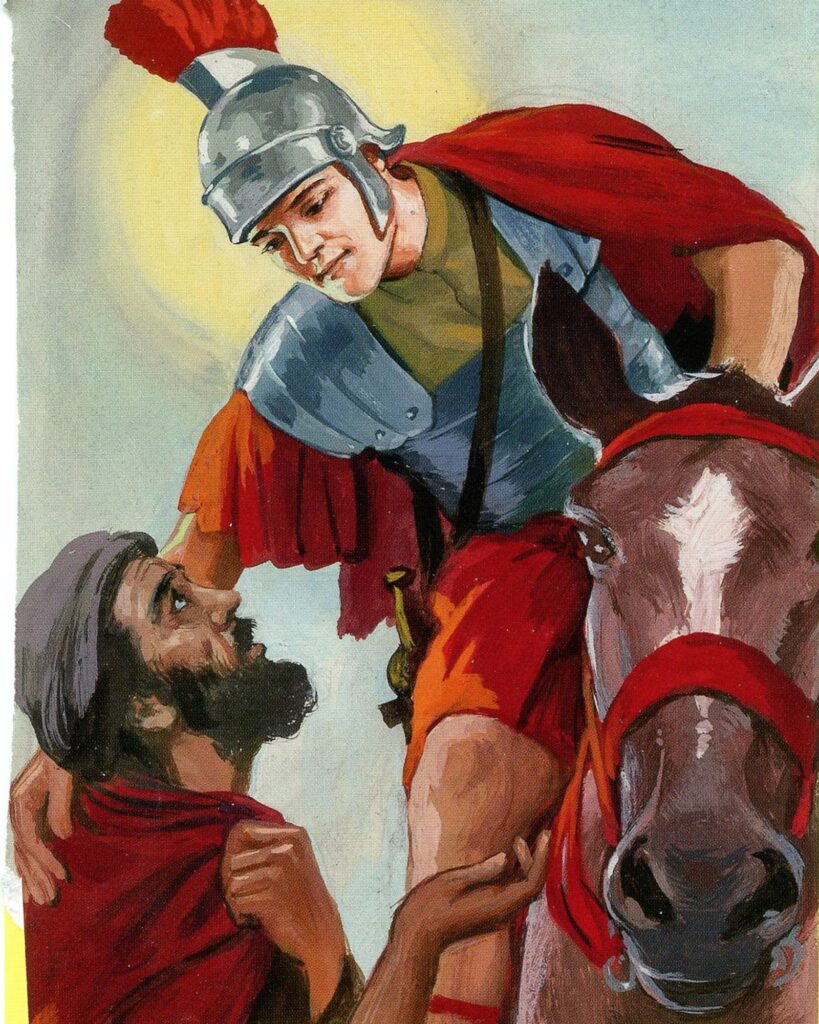

Martin of Tours, also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours in France, serving from approximately AD 316 until his death on November 8, AD 397. Initially a Roman cavalryman in Gaul, he converted to Christianity and became a dedicated bishop, especially in Tours.

He was renowned for his zealous efforts to eliminate Gallo-Roman pagan practices, often employing force against non-Christians. His legacy continues in France, where he is honored as the patron saint of the Third Republic and many other entities throughout Europe.

Martin of Tours, despite his nickname implying otherwise, was intensely focused on the apocalyptic end of the world. He was convinced that the apocalypse would happen around AD 400, coinciding with Jesus Christ’s return to battle evil.

He once wrote, “There is no doubt that the Antichrist has already been born,” predicting that this figure would rise to power upon reaching adulthood. However, this prophecy did not come true. Martin died just before AD 400, fulfilling his own prediction of meeting his maker around that time, but not the broader societal collapse he had anticipated.

9. April 6, 793

Beatus of Liébana, an 8th-century monk and theologian, lived in what is now Spain. Little is known about his early life, upbringing, and most of his adult life, leaving historians with limited information.

Despite this, his writings reveal that he was well-connected with influential religious figures throughout Spain and Europe. Beatus’s scholarly works indicate that he was a profound thinker on faith, society, and the afterlife, reflecting his deep contemplation on these subjects.

Beatus of Liébana is best known for his influential work “Commentary on the Apocalypse,” initially published in 776 and revised in 784 and 786. This text provides a vivid and enigmatic portrayal of the end times, describing the destinies of believers and non-believers and the criteria for entry into the Kingdom of Heaven.

Alongside his commentary, Beatus predicted that the apocalypse would occur on April 6, 793. When this date passed without incident, the reaction of his followers to the unfulfilled prophecy remains unknown.

8. 1368 (or 1370)

Jean de Roquetaillade, also known as John of Rupescissa, was a French Franciscan born around 1310 who lived for about sixty years during the Middle Ages. He started his education at an academy and then studied philosophy for five years in Toulouse.

Following this, he joined the Franciscan monastery in Aurillac, where he spent another five years studying theology and religious texts. His rigorous education led him to develop a critical perspective on the church’s practices and corruption. Confident in his intellectual abilities, he began making apocalyptic prophecies, which were disapproved of by church authorities.

John of Rupescissa, also known as Jean de Roquetaillade, was a French Franciscan who lived from around 1310 until the mid-14th century. He received his education at an academy and then studied philosophy for five years in Toulouse. After joining the Franciscan monastery at Aurillac, he dedicated another five years to studying theology and religious texts.

This education led him to criticize the church’s practices and corruption, resulting in his apocalyptic prophecies, which were poorly received by church leaders.

John was eventually imprisoned in various Franciscan convents across France, including one in Avignon, where he unsuccessfully appealed to Pope Clement VI for release.

While in captivity, he wrote “Visiones Seu Revelationes,” predicting the arrival of the Antichrist in 1366 and the world’s end followed by the Millennium in either 1368 or 1370. These predictions did not come true, and John likely died around that time in Avignon. His death marked the end of his apocalyptic visions, which ultimately did not impact the world as he had foreseen.

7. 1504

Sandro Botticelli, a leading figure of the Early Renaissance in Italy, is celebrated as a pioneer of the Italian Gothic period. His renowned works, including “The Birth of Venus” and “Primavera,” remain highly esteemed. Although he spent most of his life in Florence, Italy, Botticelli was deeply worried about the potential collapse of society.

In Botticelli’s “Mystical Nativity,” completed around 1500 or 1501, he offers a unique interpretation of the Nativity scene, distinguished by unconventional iconography. This painting, notable as Botticelli’s only signed work, includes text predicting that the apocalypse would occur three-and-a-half years after its completion, around 1504. This was a bold prediction for its time.

Botticelli’s “Mystical Nativity” includes a Greek inscription at the top, which translates to: “In the year 1500, amidst Italy’s turmoil, I, Alessandro, painted this during the second woe of the Apocalypse, as foretold in the eleventh chapter of Saint John. It depicts the devil’s release for three and a half years, followed by his binding in the twelfth chapter.

This is how he will be seen buried.” Botticelli believed he was living through the Great Tribulation, interpreting Europe’s hardships as signs that Christ’s Millennium was approaching, as described in Revelation. He predicted that 1504 would mark the end times, but this did not come to pass.

6. February 20, 1524 (Then, Uh, 1528)

Johannes Stöffler, an astronomer and astrologer from the late 15th and early 16th centuries, studied astronomy at a university and later became a parish priest in Justingen. While carrying out his clerical responsibilities, he also researched planetary movements and interacted with other astronomers and humanists. He notably corresponded actively with Johannes Reuchlin and even created horoscopes for him.

In 1499, while observing the stars, Stöffler noticed a rare alignment in the Pisces constellation. Known for combining his faith with contemporary scientific knowledge, he interpreted this celestial event as an omen and predicted a global flood would occur on February 20, 1524.

Despite making this prediction 25 years in advance, Stöffler was confident in its accuracy. However, when the date passed without incident, he revised his forecast to 1528, which also proved incorrect. Stöffler died in 1531, having seen two of his apocalyptic predictions fail.

5. 1555

Pierre d’Ailly, a French theologian from the late 14th and early 15th centuries, was renowned for his apocalyptic predictions. He estimated the duration of human existence on Earth to be 6,845 years by the year 1400. D’Ailly predicted that the 7,000th year, corresponding to 1555, would mark the end of the world, a belief he detailed in his writings.

Several aspects of d’Ailly’s predictions are intriguing. Firstly, the predicted apocalypse did not occur. Secondly, it is notable that d’Ailly predicted an event so far in the future that he would not be alive to see it; he died in 1420. Thirdly, d’Ailly later revised his prediction, suggesting that the Antichrist would appear in 1789, casting doubt on his earlier prophecy for 1555.

Lastly, d’Ailly’s ideas significantly influenced Christopher Columbus, who believed he was living in the end times and that d’Ailly’s predictions were accurate, even though the theologian had died 31 years before Columbus was born.

Columbus’s westward voyage, which resulted in the discovery of the New World, was inspired by d’Ailly’s teachings. Upon arriving in the Americas, Columbus believed he was triggering the apocalypse, fundamentally transforming the world as it was known in his time.

4. 1689

Pierre Jurieu was a prominent French Protestant leader in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, respected and admired by Protestants across France and Europe until his death in 1713. Witnessing the rise of Catholicism, Jurieu was deeply concerned about the rights of Protestant worshippers. As a prolific author and fervent, often controversial thinker, he gained notoriety for his works that stirred public debate. His approach to publicity elevated his status as a French Protestant during a time when Catholic influence was increasing.

From an apocalyptic perspective, Pierre Jurieu’s most famous work, “Accomplissement Des Propheties,” published in 1686, criticized the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the reduction of Protestant rights in France. He predicted that the apocalypse would occur three years later, in 1689, forecasting the overthrow of the Antichrist—whom Protestants identified as the Pope—and the revival of Protestantism.

Certainly, Jurieu’s predictions did not materialize. While it may be easy to criticize his beliefs or mock his mistakes, he was an important figure for French Protestants seeking comfort from persecution. His apocalyptic views went beyond mere consolation, influencing William of Orange’s 1688 invasion of England to defend Protestantism. Although the apocalypse did not occur in 1689 as Jurieu had predicted, his writings on the end times continued to have a significant impact.

3. 1831 (And Then 1847)

Harriet Livermore, an American preacher born just before the 19th century, emerged as one of the most prominent and prolific female preachers in U.S. history by the century’s end. She rose to prominence during the Great Awakening, promoting Protestant values like conversion, repentance, and salvation. Over time, her message incorporated radical apocalyptic themes, warning that the end times were near for America.

In 1831, Harriet Livermore started preaching about the imminent arrival of Christ’s Millennium, predicting the apocalypse would occur that year. She traveled across America and visited Jerusalem several times, proclaiming the nearness of the end times. When these predictions failed to materialize, Livermore moved westward in 1832 to avoid criticism, preaching to American Indian tribes at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and in their traditional territories. By the end of her journey, she and her followers had concluded that the apocalypse would happen in 1847.

Harriet Livermore’s prediction was notable because, during the 1830s, the Millerites had anticipated the end times in 1842, then 1843, and finally 1844. When these dates passed without incident, the Millerites faced ridicule. To avoid the same fate, Livermore set a new date for the apocalypse in 1847, diverging from their predictions. However, this prophecy also failed to materialize. Livermore lived for another two decades after her incorrect prediction and died in 1868.

2. 1873

Jonas Wendell, born in 1815 and a preacher from Pennsylvania, was a devoted follower of the Adventist movement. He drew inspiration from William Miller, the founder of the Millerites, who had predicted the world’s end in the 1840s. Despite Miller’s failed prophecies and the resulting ridicule, Wendell remained committed to Miller’s teachings. By the late 1860s, Wendell dedicated himself to biblical study and preaching, traveling through Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and New England. He often spoke at tent revivals and shows, emphasizing the imminent return of Christ. Wendell’s focus on the rapture and the Second Coming resonated with his followers, leading him to further emphasize these themes.

Jonas Wendell initially predicted Christ’s return in 1868 but later revised this date to 1873. By 1870, his predictions had gained attention and were widely reported by 1871. However, his reputation was tarnished when the Associated Press falsely reported his arrest for “improper intimacy” with a minor—a charge he denied and for which no evidence was found. Despite this controversy, Wendell’s 1873 prediction passed without incident, and he died that year. Notably, his teachings influenced Charles Taze Russell, a significant figure in Adventism and the founder of the Watchtower Movement.

1. 1977

William Branham was a prominent Christian minister in the early 20th century, renowned for his charismatic preaching that gained widespread popularity in America and Europe after World War II. He is recognized as a key figure in the second wave of Pentecostalism in the USA, which subsequently influenced the rise of modern televangelism. Branham’s dynamic sermons had a significant impact on many future religious leaders. Tragically, his life was cut short in a car accident caused by a drunk driver in 1965, but his influence continued to be felt until 1977.

Branham believed he was a prophet with the anointing of the biblical Elijah and claimed to have the foresight to predict the rapture and the imminent Second Coming of Christ. He asserted that he received an angelic visitation in rural Arizona in May 1946, during which the angel told him the rapture would occur no later than 1977. For the next twenty years until his untimely death, Branham preached this 1977 end-times date as a definitive fact to anyone who would listen.

He garnered a group of followers who began to see him as a Christ-like figure because of his prophecy. Although Branham did not seek worship for himself and preferred to focus on Jesus, his end-times prediction was too compelling for his followers to ignore. Of course, the predicted event never occurred, and Branham did not live to see his prophecy fail. This is another example, like many on this list, where time simply moved on regardless of the prediction.