During the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, the Maurya Empire conquered much of the Indian subcontinent. This era witnessed the flourishing of Prakrit and Pali literature in the north and the Tamil Sangam literature in the south. In 185 BCE, the Maurya Empire collapsed, leading to the rise of the Shunga Empire in the North and North East, while the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and Indo-Greek Kingdom claimed the North West. The Classical period saw diverse dynasties ruling various parts of India, with the Gupta Empire in the 4-6th centuries CE marking a “Golden Age of India.”

Between the 7th and 11th centuries, the Tripartite struggle centered on Kannauj involved the Pala Empire, Rashtrakuta Empire, and Gurjara-Pratihara Empire. Southern India saw the ascendancy of imperial powers like the Chalukya, Chola, Pallava, Chera, Pandyan, and Western Chalukya Empires. The Chola dynasty expanded into Southeast Asia in the 11th century, influencing mathematics and astronomy.

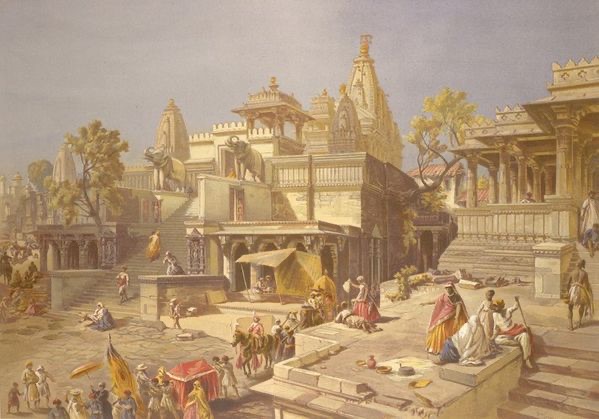

Islamic conquests started in the 8th century, and the Delhi Sultanate was established in 1206 CE. The Bengal Sultanate also emerged, while powerful Hindu states like Vijayanagara and Rajput states gained prominence. Sikhism emerged in the 15th century. The Mughal Empire dominated the 16th century, contributing to proto-industrialization and becoming a global economic power. The 18th century saw Mughal decline, paving the way for Marathas, Sikhs, Mysoreans, Nizams, and Nawabs.

From the mid-18th to mid-19th century, the East India Company gradually annexed large regions. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 led to the dissolution of the company, and India came under direct British Crown rule in the British Raj. Post-World War I, the Indian National Congress, led by Mahatma Gandhi, initiated a nonviolent struggle for independence. The British Indian Empire was partitioned in 1947, leading to the Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan gaining independence.

According to the consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans migrated to the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Despite this, the earliest human remains in South Asia date back to 30,000 years ago. Settled life, marked by the transition from foraging to farming and pastoralism, commenced around 7000 BCE in South Asia. At the Mehrgarh site, evidence reveals the early domestication of wheat, barley, goats, sheep, and cattle. By 4500 BCE, settled communities expanded, gradually evolving into the Indus Valley civilization, a contemporaneous society with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Flourishing between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE in present-day Pakistan and north-western India, this civilization was renowned for its urban planning, baked brick houses, sophisticated drainage, and water supply systems.

THE BRONZE AGE

The Indus Valley Civilisation

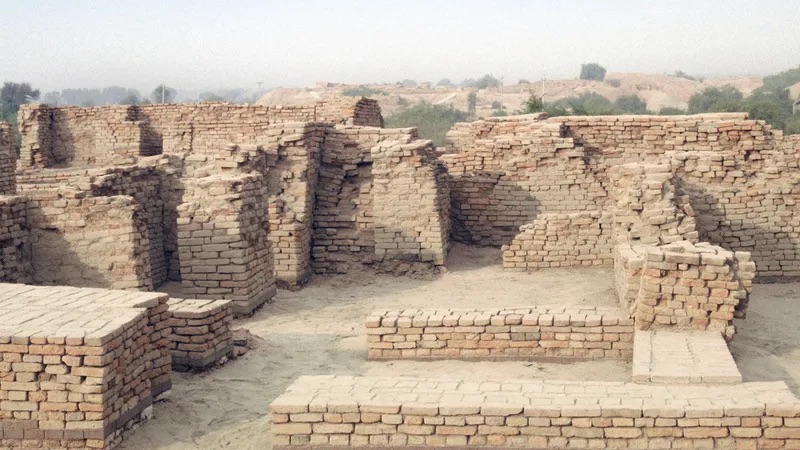

The Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization, thrived during the Bronze Age in the northwestern regions of South Asia, enduring from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, with its mature phase spanning 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. Alongside ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it stood as one of the early civilizations in the Near East and South Asia, surpassing the others in geographical extent. Encompassing vast areas from Pakistan to northeast Afghanistan and northwestern and western India, the civilization prospered in the alluvial plain of the Indus River and along monsoon-fed rivers near the Ghaggar-Hakra, a seasonal river in northwest India and eastern Pakistan.

The term “Harappan” is derived from its type site, Harappa, excavated early in the 20th century in what was once British India’s Punjab province and is now part of Punjab, Pakistan. The discovery of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro marked the culmination of archaeological efforts that began with the founding of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1861. The Early Harappan and Late Harappan cultures, alongside the renowned Mehrgarh, contributed to the civilization’s evolution.

Ancient Indus cities, like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, showcased advanced urban planning, baked brick houses, intricate drainage and water supply systems, large non-residential buildings, and sophisticated handicraft and metallurgy techniques. These cities likely housed 30,000 to 60,000 individuals each, with the entire civilization potentially numbering between one and five million people during its height. The gradual aridification of the region around the 3rd millennium BCE prompted urbanization but also contributed to a diminishing water supply, ultimately leading to the civilization’s decline and dispersal of its population to the east.

While over a thousand Mature Harappan sites have been reported, the major urban centers include Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Ganeriwala, Dholavira (a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2021), and Rakhigarhi.

The Iron Age

Following the Bronze Age, the Iron Age unfolded in the prehistory of the Indian subcontinent, aligning in part with the megalithic cultures. Among the notable Iron Age archaeological cultures were the Painted Grey Ware culture (1300–300 BCE) and the Northern Black Polished Ware (700–200 BCE). This period coincided with the transformation from the Janapadas or Vedic principalities to the sixteen Mahajanapadas or regional states in the early historic period, eventually leading to the rise of the Maurya Empire. Iron smelting, a precursor to the formal Iron Age, can be traced back several centuries before its recognized emergence.

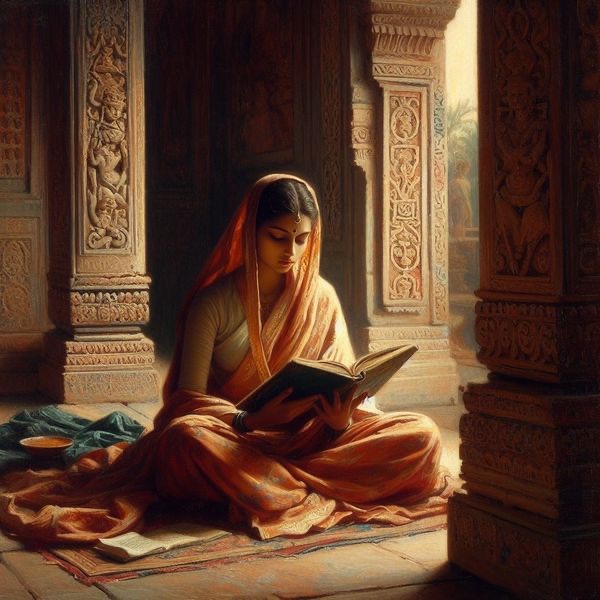

Rigveda

The Rigveda, meaning “praise” and “knowledge” in Vedic Sanskrit, stands as an ancient collection of hymns (sūktas) in Indian literature. As one of the four sacred Vedas, it holds a significant place in Hindu scriptures. Being the oldest known Vedic Sanskrit text, its early layers rank among the most ancient extant texts in any Indo-European language. The oral transmission of Rigveda’s sounds and texts dates back to the 2nd millennium BCE.

Philological and linguistic evidence suggests that the Rigveda Samhita, the core text, was likely composed in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, approximately between 1500 and 1000 BCE, although some scholars propose a broader timeframe of around 1900–1200 BCE. The text comprises the Samhita, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads. The Rigveda Samhita, consisting of 10 books (maṇḍalas) with 1,028 hymns (sūktas) totaling about 10,600 verses (ṛc), serves as the fundamental component.

The earliest composed books (Books 2 through 9) predominantly explore cosmology, rites, rituals, and praise for deities, while the more recent books (Books 1 and 10) touch on philosophical questions, societal virtues like dāna (charity), inquiries into the universe’s origin, divine nature, and other metaphysical themes. Some of its verses continue to be recited during Hindu rites of passage and celebrations, making the Rigveda one of the world’s oldest religious texts still in use.

Vedic Period

The Vedic period, occurring in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of Indian history, encompasses the composition of Vedic literature, notably the Vedas (around 1300–900 BCE). This era unfolded in the northern Indian subcontinent, bridging the decline of the urban Indus Valley civilization and a subsequent urbanization beginning in the central Indo-Gangetic Plain around 600 BCE. The Vedas, serving as liturgical texts, laid the groundwork for the influential Brahmanical ideology, evolving within the Kuru Kingdom, a tribal union of multiple Indo-Aryan tribes. These texts, coupled with archaeological findings, provide vital insights into the historical and cultural dimensions of the period.

During the Vedic period, the Vedas were meticulously composed and orally transmitted by speakers of an Old Indo-Aryan language who migrated into the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. The society during this time exhibited a patriarchal and patrilineal structure, characterized by pastoral lifestyles organized into tribes rather than kingdoms.

Between 1200 and 1000 BCE, Aryan culture expanded eastward to the fertile western Ganges Plain. Adoption of iron tools facilitated forest clearing and a shift to a settled, agricultural existence. The latter part of the Vedic period witnessed the emergence of towns, kingdoms, and a unique social hierarchy in India, culminating in the Kuru Kingdom’s codification of orthodox sacrificial rituals. Concurrently, the central Ganges Plain featured a related non-Vedic Indo-Aryan culture, Greater Magadha. The Vedic period’s conclusion marked the rise of true cities, large states (mahajanapadas), and śramaṇa movements (e.g., Jainism and Buddhism) challenging Vedic orthodoxy.

This epoch established a lasting hierarchy of social classes. Vedic religion evolved into Brahmanical orthodoxy, eventually contributing to the “Hindu synthesis” around the beginning of the Common Era. The Vedic period’s legacies include the cultural and social foundations that shaped the subsequent trajectory of Indian civilization.

Pancala

Panchala, situated in the Ganges-Yamuna Doab of the Upper Gangetic plain, was an ancient kingdom in northern India. During the Late Vedic period (around 1100–500 BCE), Panchala emerged as one of the most influential states in ancient India, maintaining a close alliance with the Kuru Kingdom. Transitioning into a confederacy by the 5th century BCE, it secured a place among the solasa (sixteen) mahajanapadas (major states) of the Indian subcontinent. After integration into the Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE), Panchala regained independence only to be annexed by the Gupta Empire in the 4th century CE.

Videha

Cc: history-maps.com

Videha, an ancient Indo-Aryan tribe in northeastern South Asia, is documented during the Iron Age. The populace of Videha, known as the Vaidehas, initially operated under a monarchy but later transitioned into a gaṇasaṅgha, an aristocratic oligarchic republic, recognized today as the Videha Republic. This republic was a constituent of the broader Vajjika League.

Kingdom of Kosala

The ancient Indian Kingdom of Kosala, known for its rich culture, spanned the region from Awadh in present-day Uttar Pradesh to Western Odisha. Emerging as a small state during the late Vedic period and maintaining connections with the neighboring Videha realm, Kosala played a key role in the Northern Black Polished Ware culture (around 700–300 BCE). The Kosala region served as the cradle for Sramana movements, contributing to the development of Jainism and Buddhism. Culturally distinct from the Painted Grey Ware culture of the Vedic period in Kuru-Panchala to its west, Kosala independently progressed, embracing urbanization and the use of iron.

In the 5th century BCE, Kosala expanded to include the territory of the Shakya clan, to which Buddha belonged. Acknowledged as one of the Solasa (sixteen) Mahajanapadas (powerful realms) in the 6th to 5th centuries BCE, Kosala’s cultural and political influence elevated it to the status of a great power, as documented in texts such as the Buddhist Anguttara Nikaya and the Jaina Bhagavati Sutra. However, a series of wars with the neighboring kingdom of Magadha weakened Kosala, leading to its absorption by Magadha in the 5th century BCE. Following the decline of the Maurya Empire and preceding the expansion of the Kushan Empire, Kosala experienced rule under the Deva dynasty, the Datta dynasty, and the Mitra dynasty.

Second Urbanisation

Between 800 and 200 BCE, the Śramaṇa movement took shape, giving rise to Jainism and Buddhism. Concurrently, the first Upanishads were authored. The period post-500 BCE witnessed the onset of the “second urbanization,” marked by the emergence of new urban settlements, notably in the Ganges plain, especially the Central Ganges plain. The groundwork for this urbanization was laid before 600 BCE, seen in the Painted Grey Ware culture of the Ghaggar-Hakra and Upper Ganges Plain.

While most Painted Grey Ware sites started as small farming villages, several dozen evolved into relatively large settlements resembling towns. The largest among them featured fortifications with ditches, moats, and embankments made of piled earth and wooden palisades. Although simpler compared to the elaborate fortifications of the large cities that followed in the Northern Black Polished Ware culture after 600 BCE, these developments marked a crucial phase.

The Central Ganges Plain, a distinct cultural area where Magadha gained prominence and became the foundation of the Maurya Empire, experienced the “second urbanization” post-500 BCE. Influenced by Vedic culture but distinct from the Kuru-Panchala region, this area played a pivotal role in the early cultivation of rice in South Asia. By 1800 BCE, it hosted an advanced Neolithic population linked to sites like Chirand and Chechar. This region became a flourishing ground for the Śramaṇic movements, leading to the origin of Jainism and Buddhism.

The Buddha

Gautama Buddha, an ascetic and spiritual teacher of South Asia, lived in the latter half of the first millennium BCE. As the founder of Buddhism, he is esteemed by followers as a fully enlightened being who imparted teachings on the path to Nirvana—freedom from ignorance, craving, rebirth, and suffering.

According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha was born in Lumbini, now in Nepal, to highborn parents of the Shakya clan. Despite his noble origin, he relinquished his family to embrace a life as a wandering ascetic. Engaging in begging, ascetic practices, and meditation, he achieved Nirvana at Bodh Gaya. Subsequently, the Buddha roamed the lower Gangetic plain, disseminating teachings and establishing a monastic order. His philosophy advocated a middle way, balancing between s*nsual indulgence and extreme asceticism, emphasizing ethical training and meditative practices like effort, mindfulness, and jhana. The Buddha’s journey concluded with his passing in Kushinagar, attaining paranirvana. His profound influence is honored by diverse religions and communities across Asia.

Nanda Empire

The Nanda dynasty held sway in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent during the 4th century BCE, possibly extending into the 5th century BCE. Rising from Magadha in eastern India, the Nandas supplanted the Shaishunaga dynasty and expanded their dominion across a significant portion of northern India. Historical accounts vary concerning the Nanda kings’ names and the duration of their rule, but according to Buddhist tradition in the Mahavamsa, they likely governed from around 345 to 322 BCE, though some theories propose an earlier start in the 5th century BCE.

Building upon the achievements of their Haryanka and Shaishunaga predecessors, the Nandas implemented a more centralized administration. They are credited with accumulating considerable wealth, likely attributed to the introduction of a new currency and taxation system. However, ancient texts indicate that the Nandas faced unpopularity among their subjects due to their low-status birth, burdensome taxation, and general misconduct. The downfall of the last Nanda king occurred at the hands of Chandragupta Maurya, founder of the Maurya Empire, and his mentor Chanakya.

Modern historians commonly identify the ruler of the Gangaridai and the Prasii, as mentioned in ancient Greco-Roman accounts, as a Nanda king. In the narratives detailing Alexander the Great’s invasion of north-western India (327–325 BCE), this kingdom is portrayed as a formidable military power. The anticipation of a conflict with this potent kingdom, coupled with the soldiers’ fatigue after nearly a decade of campaigns, sparked a mutiny among Alexander’s homesick troops, bringing an end to his Indian expedition.

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire, an influential ancient Indian Iron Age power in South Asia, emerged under Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE and endured until 185 BCE. Centralized through the conquest of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, its capital was situated in Pataliputra (modern Patna). Beyond this core, the empire’s reach relied on the allegiance of military commanders overseeing armed cities. During Ashoka’s rule (circa 268–232 BCE), the empire briefly held sway over major urban centers and thoroughfares in the Indian subcontinent, excluding the deep south. Following Ashoka’s era, a decline ensued for approximately 50 years, culminating in its dissolution in 185 BCE with Brihadratha’s assass!nation by Pushyamitra Shunga and the establishment of the Shunga Empire in Magadha.

Chandragupta Maurya, aided by Chanakya, author of Arthasastra, assembled an army and overthrew the Nanda Empire around 322 BCE. He swiftly expanded westward, conquering the satraps left by Alexander the Great, fully occupying northwestern India by 317 BCE. The Mauryan Empire also triumphed over Seleucus I, founder of the Seleucid Empire, in the Seleucid–Mauryan war, acquiring territory west of the Indus River.

Under the Mauryas, South Asia witnessed flourishing internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities, facilitated by an efficient system of finance, administration, and security. The dynasty, known for building a precursor of the Grand Trunk Road from Patliputra to Taxila, experienced a period of centralized rule under Ashoka after the Kalinga War. Ashoka’s embrace of Buddhism and support for Buddhist missionaries facilitated the faith’s expansion into Sri Lanka, northwest India, and Central Asia.

The Mauryan period, with an estimated population of 15 to 30 million in South Asia, was characterized by artistic creativity, architectural advancements, inscriptions, and significant literary contributions. However, it also saw the consolidation of caste in the Gangetic plain and the diminishing rights of women in the mainstream Indo-Aryan speaking regions of India. Key sources of information about the Mauryan times include the Arthashastra and the Edicts of Ashoka, with the Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath serving as the national emblem of the Republic of India.

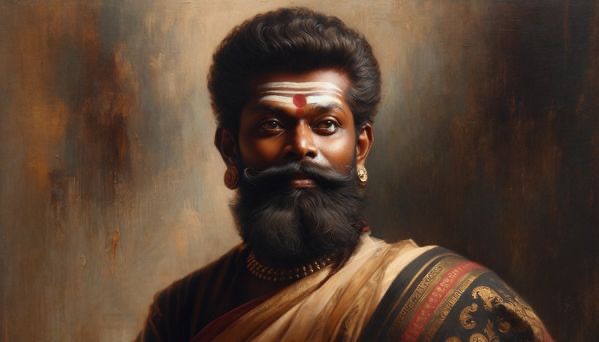

Pandya Dynasty

The Pandya dynasty, also known as the Pandyas of Madurai, stood as a prominent ancient South Indian dynasty, ranking among the triumvirate of Tamilakam’s great kingdoms alongside the Cholas and Cheras. With a lineage tracing back to at least the 4th to 3rd centuries BCE, the Pandyas experienced two imperial epochs—first from the 6th to 10th centuries CE and later during the 13th to 14th centuries CE. Their rule spanned vast territories, intermittently encompassing parts of present-day South India and northern Sri Lanka through vassal states aligned with Madurai.

The three Tamil dynasties’ rulers, including the Pandyas, were revered as the “three crowned rulers (the mu-ventar) of the Tamil country.” The dynasty’s origins and timeline present challenges for precise determination. Early Pandya chieftains governed from the ancient heartland of Madurai and the southern port of Korkai. Celebrated in Sangam literature, their historical continuity is hinted at by Graeco-Roman accounts from the 4th century BCE, Ashoka’s edicts, Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions, and coins with Tamil-Brahmi script.

From the 6th to the 9th century CE, the Pandyas shared the political landscape of south India with the Chalukyas of Badami, Rashtrakutas of the Deccan, Pallavas of Kanchi, and the Cholas. This period witnessed Pandyas asserting influence over territories like the Chola country, the ancient Chera region, Venadu, the Pallava territory, and Sri Lanka. However, their decline ensued with the ascendancy of the Cholas in the 9th century, leading to persistent conflicts.

The Pandyas enjoyed a golden age during the 13th century, particularly under Maravarman I and Jatavarman Sundara Pandya I. Maravarman I’s attempts to expand into the ancient Chola territory were thwarted by the Hoysalas. Jatavarman I successfully expanded the kingdom into the Telugu country, southern Kerala, and conquered northern Sri Lanka. Internal strife coupled with external threats, including the Khalji invasion in the early 14th century, saw the Pandyas losing territories and the establishment of the Madurai sultanate in 1334.

Traditionally associated with the legendary Sangams, held under Pandya patronage, the kingdom housed renowned temples, such as the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai. The revival of Pandya power by Kadungon in the 7th century coincided with the ascendancy of Shaivite nayanars and Vaishnavite alvars. Notably, the Pandya rulers briefly followed Jainism during a distinct period in their history.

Chola Dynasty

The Chola Dynasty, a Tamil thalassocratic empire of southern India, holds a place in history as one of the world’s longest-ruling dynasties. Dating back to the 3rd century BCE, with references found during Ashoka’s reign in the Maurya Empire, the Cholas, as one of the Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam, governed diverse territories until the 13th century CE. The rise of the “Chola Empire” began with the medieval Cholas in the mid-9th century CE, centered in the fertile valley of the Kaveri River.

The zenith of Chola power unfolded from the latter half of the 9th century to the early 13th century. Under notable rulers like Rajaraja I, Rajendra I, Rajadhiraja I, Rajendra II, Virarajendra, and Kulothunga Chola I, the dynasty became a formidable force in South and Southeast Asia. The Cholas showcased military prowess, economic strength, and cultural influence. Their expeditions to the Ganges, naval raids on Srivijaya’s cities in Sumatra, and diplomatic ties with China underscored their prominence.

From 1010 to 1153 CE, Chola territories stretched from the Maldives in the south to the banks of the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh. Rajaraja Chola conquered peninsular South India, annexed part of the Rajarata kingdom in present-day Sri Lanka, and occupied the Maldives. Rajendra Chola expanded Chola influence further, with expeditions touching the Ganges and successful campaigns in North India, Sri Lanka, and Srivijaya.

The Chola dynasty’s decline began in the early 13th century, coinciding with the ascent of the Pandyan dynasty. Despite their downfall, the Cholas left an enduring legacy with the creation of the greatest thalassocratic empire in Indian history. They introduced centralized governance, established a disciplined bureaucracy, and fostered Tamil literature and temple architecture. The Brihadisvara temple in Thanjavur, commissioned by Rajaraja Chola, exemplifies their architectural prowess. Their patronage to art, especially the development of the unique ‘Chola bronzes,’ influenced Southeast Asian art and architecture, solidifying the Cholas’ lasting impact.

CLASSICAL PERIOD

Shunger Empire

The Shunga dynasty, rooted in Magadha, governed portions of the central and eastern Indian subcontinent from approximately 187 to 78 BCE. Pushyamitra Shunga founded the dynasty by deposing the final Maurya emperor. While Pataliputra served as its initial capital, later emperors like Bhagabhadra held court in Vidisha, present-day Besnagar in Eastern Malwa.

Pushyamitra Shunga governed for 36 years, followed by his successor, his son Agnimitra. The Shunga dynasty comprised ten rulers. However, after Agnimitra’s demise, the empire swiftly fragmented. Inscriptions and coins suggest that much of northern and central India became a patchwork of independent small kingdoms and city-states, signaling the decline of Shunga influence. The empire is renowned for engaging in numerous wars against both foreign and local powers, including conflicts with the Mahameghavahana dynasty of Kalinga, the Satavahana dynasty of Deccan, the Indo-Greeks, and possibly the Panchalas and Mitras of Mathura.

During this era, art, education, philosophy, and various forms of learning thrived. The creative expressions ranged from small terracotta images to larger stone sculptures and monumental architectural wonders like the Bharhut Stupa and the renowned Great Stupa at Sanchi. The Shunga rulers notably contributed to establishing the tradition of royal patronage for learning and the arts. The script employed by the empire was a Brahmi variant, specifically used for writing Sanskrit. The Shunga Empire played a pivotal role in fostering Indian culture, particularly during a period marked by significant developments in Hindu thought. This cultural patronage significantly contributed to the empire’s prosperity and influence.

Kuninda Kingdom

The Kingdom of Kuninda, also known as Kulinda in ancient literature, was an ancient central Himalayan realm recorded from approximately the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE. It occupied the southern regions of modern Himachal Pradesh and the far western areas of Uttarakhand in northern India.

Chera Dynasty

The Chera dynasty played a significant role in the history of Kerala and the Kongu Nadu region of Western Tamil Nadu during the Sangam period. Alongside the Cholas of Uraiyur and the Pandyas of Madurai, the early Cheras were recognized as one of the three major powers (muventar) in ancient Tamilakam during the early centuries of the Common Era.

Situated advantageously for maritime trade through Indian Ocean networks, the Chera country engaged in the exchange of spices, particularly black pepper, with Middle Eastern and Graeco-Roman merchants. During the early historical period (c. 2nd century BCE – c. 3rd century CE), the Cheras centered their rule at Vanchi and Karur in Kongu Nadu, overseeing harbors at Muchiri (Muziris) and Thondi (Tyndis) on the Kerala coast. Their domain extended from Alappuzha in the south to Kasaragod in the north, covering the Malabar Coast, Palakkad Gap, Coimbatore, Dharapuram, Salem, and Kolli Hills. The southern region of present-day Kerala, from Thiruvananthapuram to southern Alappuzha, was under the Ay dynasty, more closely linked to the Pandya dynasty of Madurai.

These early historic pre-Pallava Tamil polities were shaped by kinship-based redistributive economies, pastoral-agrarian subsistence, and predatory politics. Inscriptions and Brahmi cave labels mention Chera rulers, including Ilam Kadungo, and portrait coins display Chera symbols like the bow and arrow. The anthologies of early Tamil texts, such as the Chilapathikaram, provide insights into the Cheras’ history. The decline of Chera power occurred around the 3rd-5th century CE.

In the early medieval period, Cheras of the Kongu country controlled western Tamil Nadu with an empire in central Kerala. The Chera Perumal kingdom and Kongu Chera kingdom detached around the 8th-9th century CE. By the 10th/11th century CE, Kongu Cheras seem to have been absorbed into the Pandya political system. Even after the dissolution of the Perumal kingdom, inscriptions and grants continued to refer to the country and its people as the “Cheras or Keralas.”

Venad Cheras, based in the port of Kollam in south Kerala, claimed ancestry from the Perumals. Cheranad, an erstwhile province in the Zamorin’s kingdom, included parts of present-day Tirurangadi and Tirur Taluks in Malappuram district. In the modern period, rulers of Cochin and Travancore in Kerala also claimed the title “Chera.”

Satavahana Dynasty

The Satavahanas, also known as the Andhras in the Puranas, were an ancient South Asian dynasty centered in the Deccan region. Scholars generally agree that Satavahana rule likely commenced in the late 2nd century BCE and persisted until the early 3rd century CE. Though some sources trace their beginnings as early as the 3rd century BCE based on Puranic accounts, this lacks archaeological corroboration. The Satavahana kingdom primarily encompassed present-day Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Maharashtra, with intermittent control over parts of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Karnataka. Notably, the dynasty had various capital cities, including Pratishthana (Paithan) and Amaravati (Dharanikota).

While the dynasty’s origin remains uncertain, Puranas suggest that their inaugural king overthrew the Kanva dynasty. In the post-Maurya period, the Satavahanas brought stability to the Deccan, resisting foreign invasions, notably from the Saka Western Satraps. The zenith of their rule occurred under Gautamiputra Satakarni and his successor Vasisthiputra Pulamavi. However, the kingdom fragmented into smaller states by the early 3rd century CE.

The Satavahanas were early issuers of Indian state coinage adorned with images of their rulers. Serving as a cultural bridge, they played a crucial role in facilitating trade and the exchange of ideas and culture between the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the southern tip of India. The dynasty supported Hinduism and Buddhism, actively patronizing Prakrit literature.

Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire, originating from the Yuezhi in Bactrian territories around the early 1st century, expanded to cover much of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India. Its reach extended at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi, evidenced by inscriptions from the era of Kushan Emperor Kanishka the Great.

The Kushans were likely one of five Yuezhi confederation branches, Indo-European nomads, possibly of Tocharian origin, migrating from northwestern China to settle in ancient Bactria. The dynasty’s founder, Kujula Kadphises, embraced Greek religious ideas in line with Greco-Bactrian tradition and also followed Hindu traditions, particularly as a devotee of the Hindu God Shiva. The Kushans, under Emperor Kanishka’s leadership, became significant patrons of Buddhism, playing a pivotal role in its spread to Central Asia and China. They incorporated elements of Zoroastrianism into their pantheon.

Initially using Greek for administrative purposes, the Kushans later adopted the Bactrian language. Emperor Kanishka expanded north of the Karakoram mountains, establishing direct routes from Gandhara to China that facilitated the spread of Mahayana Buddhism. The Kushan Empire engaged in diplomatic relations with the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, Aksumite Empire, and Han dynasty of China, becoming a focal point in major civilizations.

In the 3rd century CE, the Kushan Empire fragmented into semi-independent kingdoms, succumbing to Sasanians from the west, giving rise to the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom in Sogdiana, Bactria, and Gandhara. By the 4th century, the Guptas from the east pressed in, and eventually, the remaining Kushan and Kushano-Sasanian realms fell to northern invaders, first the Kidarites and then the Hephthalites.

Vakataka Dynasty

The Vakataka dynasty, emerging from the Deccan in the mid-3rd century CE, is believed to have held sway from the southern fringes of Malwa and Gujarat in the north to the Tungabhadra River in the south, and from the Arabian Sea in the west to the borders of Chhattisgarh in the east. As prominent successors to the Satavahanas in the Deccan, they coexisted with the Guptas in northern India, constituting a Brahmin dynasty.

The founder, Vindhyashakti (c. 250 – c. 270 CE), remains shrouded in mystery. Territorial expansion commenced during the reign of his son, Pravarasena I. The Vakataka dynasty is believed to have splintered into four branches after Pravarasena I, with two branches known and two remaining elusive. The identified branches are the Pravarapura-Nandivardhana and the Vatsagulma branches. In the 4th century CE, Gupta Emperor Chandragupta II, cementing ties with the Vakataka royal family through marriage, secured the annexation of Gujarat from the Saka Satraps. The Chalukyas of Badami succeeded the Vakataka power in the Deccan.

Renowned for their patronage of the arts, architecture, and literature, the Vakatakas undertook significant public works, leaving behind a tangible legacy. The Ajanta Caves, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, showcase their support for culture and learning, particularly the rock-cut Buddhist viharas and chaityas, constructed under the auspices of Vakataka Emperor Harishena.

Pallava Dynasty

The Pallava dynasty, reigning from 275 CE to 897 CE in the southern region of India known as Tondaimandalam, rose to prominence after the decline of the Satavahana dynasty, to which they were once feudatories.

Under the rule of Mahendravarman I (600–630 CE) and Narasimhavarman I (630–668 CE), the Pallavas emerged as a dominant force, exercising control over the southern Telugu Region and the northern parts of the Tamil region for nearly six centuries until the late 9th century. Throughout their long reign, they engaged in persistent conflicts with the Chalukyas of Badami to the north and the Tamil kingdoms of Chola and Pandyas to the south. In the 9th century, the Chola ruler Aditya I dealt the final blow to the Pallavas, marking the end of their era.

The Pallavas’ enduring legacy lies in their patronage of architecture, exemplified by the magnificent Shore Temple, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Mamallapuram. Kancheepuram served as the thriving capital of the Pallava kingdom. Renowned for their sculptural and temple-building prowess, the Pallavas laid the groundwork for medieval South Indian architecture. They developed the Pallava script, a precursor to Grantha, which later influenced various Southeast Asian scripts, including Khmer. The Chinese traveler Xuanzang praised the Pallavas for their benevolent rule during his visit to Kanchipuram.

Gupta Empire

The period from the decline of the Maurya Empire in the 3rd century BCE to the conclusion of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century CE is commonly known as the “Classical” period in India. This era can be subdivided based on various periodizations. The Classical period commences with the waning of the Maurya Empire and the simultaneous ascent of the Shunga and Satavahana dynasties. The Gupta Empire (4th–6th century) is often hailed as the “Golden Age” of Hinduism, although numerous kingdoms held sway over India during these centuries. The Southern Indian Sangam literature also flourished from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE. Throughout this period, India’s economy is estimated to have been the world’s largest, constituting between one-third and one-quarter of global wealth from 1 CE to 1000 CE.

Kadamba Dynasty

The Kadambas (345–540 CE) were an ancient royal dynasty in Karnataka, India, that held sway over northern Karnataka and the Konkan region from their capital in Banavasi, present-day Uttara Kannada district. Founded by Mayurasharma around 345 CE, the kingdom, over time, demonstrated the potential to expand into imperial dimensions. Signs of their imperial aspirations are evident in the titles and epithets adopted by its rulers, as well as in their marital alliances with other kingdoms and empires like the Vakatakas and Guptas in northern India. Mayurasharma, possibly with the assistance of local tribes, defeated the armies of the Pallavas of Kanchi, asserting sovereignty. The Kadamba influence reached its zenith during the reign of Kakusthavarma.

The Kadambas, alongside the Western Ganga Dynasty, were among the earliest indigenous kingdoms to assert autonomous rule over the land. Starting from the mid-6th century, the dynasty continued its governance, initially as vassals to larger Kannada empires like the Chalukyas and later the Rashtrakutas, spanning over five centuries. During this period, the Kadambas diversified into minor dynasties, with notable branches such as the Kadambas of Goa, Kadambas of Halasi, and Kadambas of Hangal. In the pre-Kadamba era, the dominant ruling families in the Karnataka region, the Mauryas and later the Satavahanas, were external to the region, with the center of power located beyond present-day Karnataka.

Kamarupa Kingdom

Kamarupa, an early state in the Classical period on the Indian subcontinent, served as the first recorded kingdom of Assam, along with Davaka.

Enduring from 350 CE to 1140 CE, Kamarupa absorbed Davaka in the 5th century CE. Governed by three dynasties with capitals in present-day Guwahati, North Guwahati, and Tezpur, Kamarupa reached its zenith, encompassing the entire Brahmaputra Valley, North Bengal, Bhutan, and the northern part of Bangladesh. At times, it also controlled portions of present-day West Bengal, Bihar, and Sylhet.

While the historical kingdom disintegrated by the 12th century, giving way to smaller political entities, the concept of Kamarupa persisted. Ancient and medieval chroniclers continued to refer to a section of this realm as Kamrup. In the 16th century, the Ahom kingdom rose to prominence, adopting the legacy of the ancient Kamarupa kingdom and aspiring to extend their dominion to the Karatoya River.

Chalukya Dynasty

The Chalukya Empire exerted its influence over extensive regions of southern and central India from the 6th to the 12th centuries, characterized by three interrelated yet distinct dynasties. The inaugural dynasty, recognized as the “Badami Chalukyas,” governed from Vatapi (modern Badami) starting in the mid-6th century. The emergence of the Badami Chalukyas coincided with the waning authority of the Kadamba kingdom of Banavasi, and their ascendancy accelerated notably under the rule of Pulakeshin II. This Chalukyan rule represents a pivotal juncture in South Indian history and stands as a golden era in Karnataka’s historical narrative. The political landscape of South India transitioned from fragmented kingdoms to substantial empires with the prominence of the Badami Chalukyas. Originating in Southern India, this kingdom seized control, unifying the entire expanse between the Kaveri and Narmada rivers. The ascendancy of this empire brought forth efficient governance, flourishing overseas trade and commerce, and the evolution of a distinctive architectural style known as “Chalukyan architecture.” The Chalukya dynasty held sway over southern and central India, initially from Badami in Karnataka between 550 and 750 and subsequently from Kalyani between 970 and 1190.

EARLY MEDIEVAL PERIOD

The onset of early medieval India unfolded subsequent to the demise of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century CE. This epoch encapsulates the “Late Classical Age” of Hinduism, commencing after the fall of the Gupta Empire and the dissolution of the Harsha Empire in the 7th century CE. It also marks the initiation of Imperial Kannauj, paving the way for the Tripartite struggle. The era concluded in the 13th century with the ascent of the Delhi Sultanate in Northern India and the culmination of the Later Cholas, culminating with the passing of Rajendra Chola III in 1279 in Southern India. Nevertheless, remnants of the Classical period persisted until the decline of the Vijayanagara Empire around the 17th century in the southern region.

From the 5th to the 13th century, Śrauta sacrifices witnessed a decline, while initiatory traditions of Buddhism, Jainism, and predominantly Shaivism, Vaishnavism, and Shaktism flourished in royal courts. This era bore witness to the creation of some of India’s most exquisite art, regarded as the pinnacle of classical development, and the evolution of prominent spiritual and philosophical systems that endured in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Pushyabhuti Dynasty

The Pushyabhuti dynasty, also recognized as the Vardhana dynasty, governed northern India during the 6th and 7th centuries. Its pinnacle was realized under the reign of its final ruler, Harsha Vardhana (c. 590–647 CE), and the Empire of Harsha encompassed a significant portion of north and north-western India, stretching from Kamarupa in the east to the Narmada River in the south. Initially seated in Sthanveshvara (in present-day Kurukshetra district, Haryana), Harsha later established Kanyakubja (modern Kannauj, Uttar Pradesh) as his capital, from where he governed until 647 CE.

Guhila Dynasty

The Guhilas of Medapata, commonly referred to as the Guhilas of Mewar, constituted a Rajput dynasty that held sway over the Medapata region in the present-day state of Rajasthan, India. Initially serving as Gurjara-Pratihara feudatories in the late 8th and 9th centuries, the Guhila kings later gained independence during the early 10th century, forming alliances with the Rashtrakutas. Their principal capitals included Nagahrada (Nagda) and Aghata (Ahar), leading to their identification as the Nagda-Ahar branch of the Guhilas.

The Guhilas asserted their independence following the waning influence of the Gurjara-Pratiharas in the 10th century, led by Rawal Bharttripatta II and Rawal Allata. Throughout the 10th to 13th centuries, they engaged in military conflicts with neighboring powers, including the Paramaras, Chahamanas, Delhi Sultanate, Chaulukyas, and Vaghelas. In the late 11th century, Paramara king Bhoja intervened in Guhila affairs, potentially deposing a ruler and installing another from the branch.

During the mid-12th century, the Guhila dynasty underwent a division into two branches. The senior branch, whose rulers were later referred to as Rawal, governed from Chitrakuta (modern Chittorgarh) and met its demise with Ratnasimha’s defeat during the 1303 Siege of Chittorgarh by the Delhi Sultanate. Simultaneously, the junior branch emerged from the village of Sisodia, adopting the title Rana, thus laying the foundation for the Sisodia Rajput dynasty.

Gurjara-Pratihara Dynasty

The Gurjara-Pratiharas played a crucial role in halting Arab armies advancing east of the Indus River. Nagabhata I achieved a significant victory against the Arab forces led by Junaid and Tamin during the Caliphate campaigns in India. Under Nagabhata II, the Gurjara-Pratiharas rose to prominence as the most influential dynasty in northern India. His successor, Ramabhadra, had a brief rule before passing the reins to his son, Mihira Bhoja. The Pratihara Empire witnessed its zenith of prosperity and power under the rule of Bhoja and his successor Mahendrapala I.

During Mahendrapala’s era, the Pratihara Empire expanded its territory significantly, rivalling the expanse of the Gupta Empire. Stretching from the western border of Sindh to Bihar in the east, and from the Himalayas in the north to areas beyond the Narmada in the south, the empire’s reach triggered a three-way power struggle with the Rashtrakuta and Pala empires for dominance over the Indian subcontinent. In this period, Imperial Pratihara adopted the prestigious title of Maharajadhiraja of Āryāvarta (Great King of Kings of India).

As the 10th century unfolded, various feudatories of the empire seized the opportunity presented by the Gurjara-Pratiharas’ temporary weakness, declaring their independence. Notable among these were the Paramaras of Malwa, the Chandelas of Bundelkhand, the Kalachuris of Mahakoshal, the Tomaras of Haryana, and the Chauhans of Rajputana.

Pala Empire

Founded by Gopala I, the Pala Empire, a Buddhist dynasty ruling from Bengal in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, emerged as a unifying force in Bengal after the decline of Shashanka’s Gauda Kingdom.

Devoted to the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism, the Palas also extended their patronage to Shaivism and Vaishnavism. The suffix “Pala,” signifying “protector,” adorned the names of all Pala monarchs. Under the leadership of Dharmapala and Devapala, the empire reached its zenith. Dharmapala is credited with the conquest of Kanauj and the expansion of his influence to the farthest reaches of India in the northwest.

The Pala Empire is often regarded as Bengal’s golden era. Dharmapala played a pivotal role in founding Vikramashila and revitalizing Nalanda, renowned as one of the earliest great universities in recorded history. Nalanda flourished under the generous patronage of the Pala Empire. Additionally, the Palas constructed numerous viharas and maintained robust cultural and commercial connections with Southeast Asian countries and Tibet. Sea trade significantly contributed to the prosperity of the Pala Empire, as noted by the Arab merchant Suleiman, who marveled at the magnitude of the Pala army in his memoirs.

Rashtrakuta Dynasty

Established by Dantidurga circa 753, the Rashtrakuta Empire held sway from its capital, Manyakheta, for nearly two centuries. At its zenith, the Rashtrakutas governed the region from the Ganges River and Yamuna River doab in the north to Cape Comorin in the south, a period marked by political expansion, architectural marvels, and significant literary contributions.

While the early rulers of the dynasty were Hindu, the later leaders embraced Jainism. Govinda III and Amoghavarsha emerged as notable administrators within this dynasty. Amoghavarsha, reigning for 64 years, not only excelled as a ruler but also authored the Kavirajamarga, the earliest known Kannada work on poetics. Architectural brilliance flourished in the Dravidian style, epitomized by the Kailasanath Temple at Ellora, along with notable structures like the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal in Karnataka.

The Rashtrakuta Empire earned acclaim from the Arab traveler Suleiman, who recognized it as one of the world’s four great empires. This era marked the onset of a golden age in southern Indian mathematics. Mahāvīra, a renowned south Indian mathematician, resided in the Rashtrakuta Empire, and his influential text significantly impacted subsequent medieval mathematicians in the region. The Rashtrakuta rulers were also patrons of literary figures who composed works in diverse languages, ranging from Sanskrit to the Apabhraṃśas.

Medieval Chola Dynasty

The Medieval Cholas ascended to prominence in the mid-9th century CE, establishing one of India’s most formidable empires. Successfully unifying South India under their governance, they wielded naval prowess to extend influence across Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka. Engaging in trade, they maintained contacts with the Arabs in the west and the Chinese in the east.

Persistent conflicts between the Medieval Cholas and Chalukyas for control of Vengi gradually depleted both empires, contributing to their eventual decline. Through a series of alliances spanning decades, the Chola dynasty eventually merged into the Eastern Chalukyan dynasty of Vengi, subsequently uniting under the Later Cholas.

Western Chalukya Empire

The Western Chalukya Empire exerted control over a vast expanse in the western Deccan and South India from the 10th to the 12th centuries. Encompassing regions between the Narmada River in the north and the Kaveri River in the south, the Chalukyas held sway over subordinate ruling families, including the Hoysalas, Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, Kakatiya dynasty, and Southern Kalachuris. The latter gained independence as the influence of the Western Chalukyas diminished in the latter half of the 12th century.

Renowned for their distinctive architectural style, a transitional blend bridging early Chalukya and later Hoysala influences, the Western Chalukyas left a mark on the landscape. Notable examples include the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi, the Mallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti, the Kallesvara Temple at Bagali, Siddhesvara Temple at Haveri, and the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi. This era played a pivotal role in the cultural development of Southern India, fostering literature in native languages like Kannada and Sanskrit. Influential figures such as the philosopher-statesman Basava and the mathematician Bhāskara II emerged under the patronage of the Western Chalukya kings.

Ghaznavid Campaigns

In 1001, Mahmud of Ghazni initiated his first invasion, targeting present-day Pakistan and subsequently extending into parts of India. During this campaign, Mahmud triumphed over the Hindu Shahi ruler Jayapala, who, having relocated his capital to Peshawar (modern Pakistan), was captured and later released. Jayapala took his own life, and his son Anandapala succeeded him.

In 1005, Mahmud of Ghazni launched an invasion of Bhatia (likely Bhera), and the following year, he targeted Multan. During this period, Anandapala’s forces engaged Mahmud’s army. In 1006, Mahmud dealt a decisive blow to Sukhapala, the ruler of Bathinda, who had rebelled against the Shahi kingdom.

The pivotal Battle of Chach took place in 1008-1009, resulting in Mahmud’s victory over the Hindu Shahis. Subsequently, in 1013, during Mahmud’s eighth expedition into eastern Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Shahi kingdom, then under Trilochanapala (Anandapala’s son), was toppled.

LATE MEDIEVAL PERIOD

Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate, an Islamic empire based in Delhi, spanned significant portions of South Asia for 320 years (1206–1526). Following the Ghurid dynasty’s invasion of the subcontinent, five dynasties successively ruled the Delhi Sultanate: the Mamluk dynasty (1206–1290), Khalji dynasty (1290–1320), Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414), Sayyid dynasty (1414–1451), and Lodi dynasty (1451–1526). Encompassing regions in present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and parts of southern Nepal, it was established by Ghurid conqueror Muhammad Ghori after defeating the Rajput Confederacy led by Prithviraj Chauhan in 1192 CE.

Originating from the Turkic slave-generals of Muhammad Ghori, such as Yildiz, Aibak, and Qubacha, who divided the Ghurid territories, the Delhi Sultanate saw the Mamluks overthrown in the Khalji revolution, transferring power to an Indo-Muslim nobility. The ensuing Khalji and Tughlaq dynasties witnessed rapid Muslim conquests in South India. Under Muhammad bin Tughluq, the sultanate reached its zenith but faced decline due to Hindu reconquests, asserting independence by Hindu kingdoms like Vijayanagara Empire and Mewar, and the emergence of new Muslim sultanates like the Bengal Sultanate. In 1526, it was conquered, marking the rise of the Mughal Empire.

The sultanate integrated the Indian subcontinent into a global cosmopolitan culture, contributed to Hindustani language development, and featured the reign of Razia Sultana, a notable female ruler. The era included desecration of Hindu and Buddhist temples by Bakhtiyar Khalji, leading to the decline of Buddhism in East India, and the establishment of Islamic culture through migration from Central Asia and West Asia.

Vijayanagara Empire

Established in 1336 on the Deccan Plateau of South India, the Vijayanagara Empire, also known as the Karnata Kingdom, emerged under the Sangama dynasty’s Harihara I and Bukka Raya I. Originating from a pastoralist cowherd community claiming Yadava lineage, it thwarted Turkic Islamic invasions by the late 13th century and reached its zenith, subjugating South India’s ruling families and expanding beyond the Tungabhadra-Krishna river doab, including annexing Odisha (ancient Kalinga) from the Gajapati Kingdom. The empire, named after its capital Vijayanagara near Hampi, persisted until 1646, though declining after the 1565 Battle of Talikota.

Noteworthy for Hampi’s ruins, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Karnataka, the Vijayanagara Empire influenced temple architecture, merging diverse traditions into its distinctive style. The empire’s legacy includes monuments, with Hampi being prominent, and innovations in Hindu temple construction. It facilitated technological advancements like water management for irrigation through efficient administration and extensive overseas trade. Vijayanagara’s patronage fostered cultural and literary peaks in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, and Sanskrit, exploring astronomy, mathematics, medicine, fiction, musicology, historiography, and theater. Carnatic music, Southern India’s classical music, flourished. The empire’s era transcended regionalism, promoting Hinduism as a unifying force, leaving an indelible mark on the history of Southern India.

Kingdom of Mysore

Established around 1399 near the modern city of Mysore, the Kingdom of Mysore, ruled predominantly by the Hindu Wodeyar family, began as a vassal state under the Vijayanagara Empire. In the 17th century, under Narasaraja Wodeyar I and Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar, it expanded its territory, annexing southern Karnataka and parts of Tamil Nadu, evolving into a powerful state in the southern Deccan. Muslim rule briefly altered its administrative style, adopting a Sultanate model and sparking conflicts with the Marathas, Nizam of Hyderabad, Kingdom of Travancore, and the British, leading to the four Anglo-Mysore Wars.

While the First Anglo-Mysore War saw success and the Second ended in a stalemate, the Third and Fourth resulted in defeat. Tipu Sultan’s death in the Siege of Seringapatam (1799) led to the annexation of significant portions by the British, marking the conclusion of Mysorean hegemony over South India. Through a subsidiary alliance, the British reinstated the Wodeyars to power, transforming Mysore into a princely state. The Wodeyars continued their rule until India gained independence in 1947, and Mysore joined the Union of India.

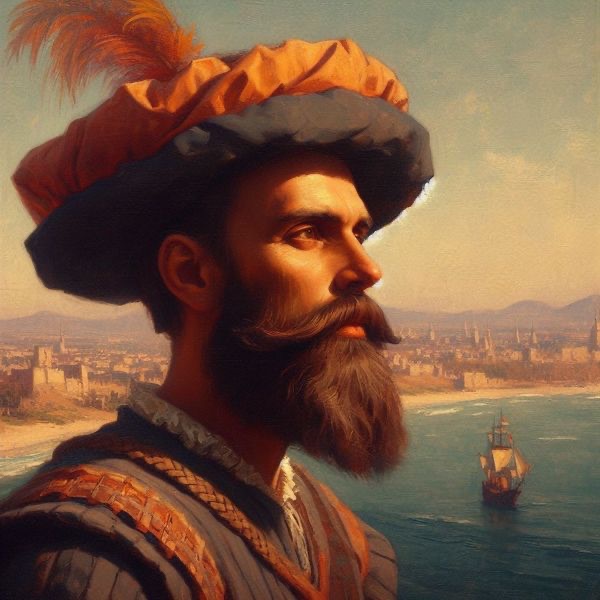

First Europeans Reach India

In 1498, Vasco de Gama’s fleet reached Kappadu near Kozhikode on the Malabar Coast (present-day Kerala, India). The King of Calicut, the Zamorin, returned from Ponnani to Calicut upon hearing of the foreign fleet’s arrival. Despite a grand procession and traditional hospitality, an audience with the Zamorin yielded no concrete results. When asked about their purpose, da Gama’s fleet stated they came “in search of Christians and spices.” Gifts from Dom Manuel, including scarlet cloth, hats, corals, almasares, brass vessels, sugar, oil, and honey, failed to impress. The absence of gold or silver puzzled officials, and Muslim merchants considered da Gama a mere pirate. The King rejected da Gama’s request to leave a factor in charge, insisting on customs duty in gold, straining relations. Irritated, da Gama forcibly took some Nairs and sixteen fishermen with him.

Portuguese India

The Portuguese State of India, established six years after Vasco da Gama’s sea route discovery to the Indian subcontinent, was a territory within the Portuguese Empire. The capital of Portuguese India functioned as the administrative hub overseeing a network of military forts and trade posts across the Indian Ocean.

EARLY MODERN PERIOD

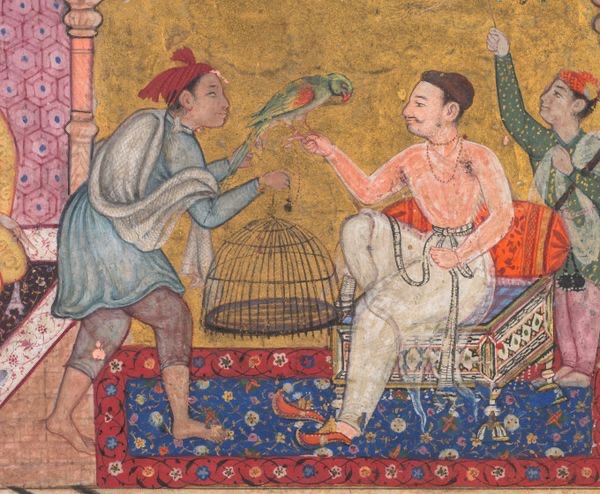

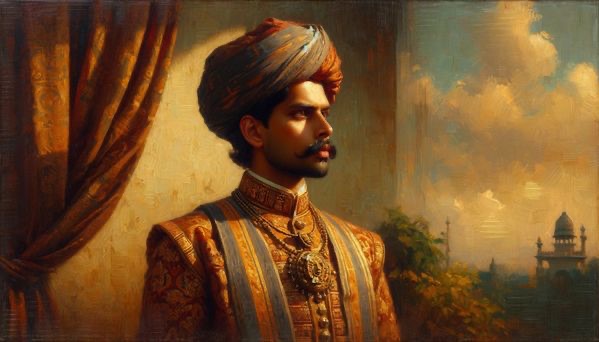

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire, spanning the 16th to 19th centuries, governed vast regions of South Asia from the Indus River basin in the west to Assam and Bangladesh in the east. Initially established in 1526 by Babur, a warrior chieftain from present-day Uzbekistan, the Mughal imperial structure evolved under Akbar in 1600 and reached its peak under Aurangzeb by 1720. After Aurangzeb’s reign, the empire contracted and was formally dissolved by the British Raj post the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Despite its military origins, the Mughal Empire adopted inclusive administrative practices, fostering cultural diversity and contributing to India’s economic growth through agricultural taxes and trade.

East Company India

The East India Company, established in 1600 and disbanded in 1874, originated as an English joint-stock company trading in the Indian Ocean region, first with the East Indies and later with East Asia. It expanded its influence, seizing control of significant portions of the Indian subcontinent and colonizing parts of Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. At its zenith, the company ranked as the world’s largest corporation, possessing its own formidable armed forces known as the Presidency armies. With a profound impact on global trade, the East India Company reversed the historical westward flow of Western bullion.

Initially chartered as the “Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East-Indies,” the company dominated half of the world’s trade in the mid-1700s and early 1800s, dealing in commodities like cotton, silk, indigo dye, sugar, spices, tea, and opium. It played a pivotal role in establishing the foundations of the British Empire in India.

Taking military and administrative control, the company governed vast regions in India from 1757, following the Battle of Plassey, until 1858, when direct British Crown rule was instituted after the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Persistent financial challenges and government intervention led to the company’s dissolution in 1874, rendered obsolete by the British Raj’s assumption of its functions and absorption of its armies.

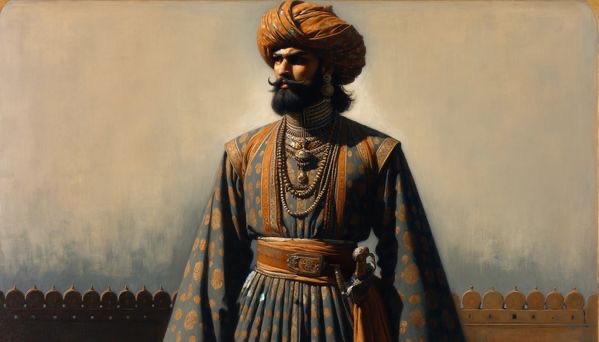

Maratha Confederacy

Founded by Chatrapati Shivaji, the Maratha Confederacy gained prominence under Peshwa Bajirao I in the early 18th century, consolidating its rule over much of South Asia. The Marathas played a pivotal role in ending Mughal dominance, defeating them in the Battle of Delhi in 1737. Military campaigns against the Mughals, Nizam, Nawab of Bengal, and the Durrani Empire expanded their territory significantly by 1760. They even contemplated placing Vishwasrao Peshwa on Delhi’s throne.

At its zenith, the Maratha empire spanned from Tamil Nadu to Peshawar and Bengal. The northwestern expansion was halted after the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761, but Peshwa Madhavrao I reestablished Maratha authority in the north within a decade. Madhavrao I granted semi-autonomy to strong knights, forming a confederacy of United Maratha states under various leaders.

Intervention by the East India Company in a Peshwa family succession struggle led to the First Anglo-Maratha War in 1775, resulting in a Maratha victory. Despite their triumph, the Marathas faced defeat in the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars (1805–1818), ultimately leading to East India Company control over most of India.

Company Rule in India

Company rule in India, stemming from the British East India Company’s dominance over the Indian subcontinent, is often considered to have started around 1757 after the Battle of Plassey. The period saw significant milestones, such as the Company being granted the right to collect revenue (diwani) in Bengal and Bihar in 1765. Another pivotal moment was in 1773 when the Company established a capital in Calcutta, appointed its first Governor-General, Warren Hastings, and took a direct role in governance. This rule endured until 1858, when the British government took over after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, instituting the new British Raj through the Government of India Act 1858.

Company expansion manifested through the annexation of Indian states, leading to direct governance. The North-Western Provinces, Delhi, Assam, and Sindh were annexed, while Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, and Kashmir followed after the Anglo-Sikh Wars (1849–56). Berar and the state of Oudh were annexed in 1854 and 1856, respectively. Simultaneously, treaties were negotiated where Indian rulers recognized the Company’s hegemony in exchange for limited autonomy. The company, constrained financially, sought political alliances, with subsidiary alliances being crucial during the initial 75 years of rule, covering territories that constituted a significant portion of India. These alliances provided a cost-effective method of indirect rule, avoiding the expenses and challenges of direct administration.

Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire, governed by adherents of the Sikh religion, held sway over the Northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent from 1799 to 1849. Established on the Khalsa foundation, the empire, centered around Punjab, emerged under Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780–1839), uniting various Punjabi Misls of the Sikh Confederacy.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh adeptly consolidated northern India using his Sikh Khalsa Army, trained in European military tactics and equipped with modern technologies. With strategic prowess, he defeated Afghan forces, concluding the Afghan-Sikh Wars. Expanding gradually, he incorporated central Punjab, Multan, Kashmir, and the Peshawar Valley into his realm.

At its zenith in the 19th century, the empire spanned from the Khyber Pass in the west to Kashmir in the north, extending to Sindh in the south and along the Sutlej River to Himachal in the east. Following Ranjit Singh’s demise, internal strife weakened the empire, leading to conflicts with the British East India Company. The challenging First Anglo-Sikh War and Second Anglo-Sikh War marked the decline of the Sikh Empire, ultimately making it one of the last regions in the Indian subcontinent to succumb to British conquest.

MODERN PERIOD

Indian Independence Movement

Rewrite The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947. The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged from Bengal. It later took root in the newly formed Indian National Congress with prominent moderate leaders seeking the right to appear for Indian Civil Service examinations in British India, as well as more economic rights for natives. The first half of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards self-rule by the Lal Bal Pal triumvirate, Aurobindo Ghosh and V. O. Chidambaram Pillai.

The last stages of the self-rule struggle from the 1920s was characterized by Congress’ adoption of Gandhi’s policy of non-violence and civil disobedience. Intellectuals such as Rabindranath Tagore, Subramania Bharati, and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay spread patriotic awareness. Female leaders like Sarojini Naidu, Pritilata Waddedar, and Kasturba Gandhi promoted the emancipation of Indian women and their participation in the freedom struggle. B. R. Ambedkar championed the cause of the disadvantaged sections of Indian society.

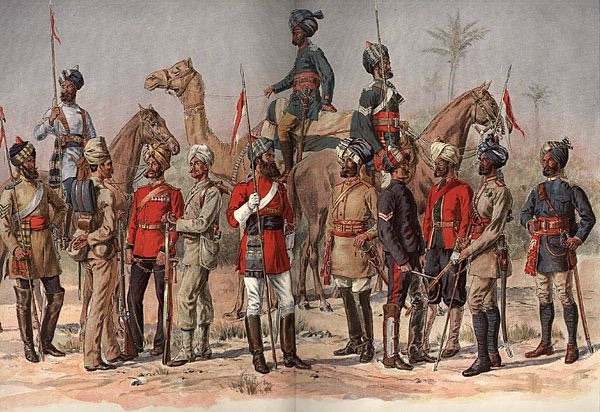

Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 marked a significant uprising by soldiers in the employ of the British East India Company across northern and central India against the company’s rule. The catalyst for the mut!ny was the introduction of new g*npowder cartridges for the Enfield rifle, which disregarded local religious prohibitions. The pivotal figure in the mut!ny was Mangal Pandey. The rebellion was fueled by underlying grievances related to British taxation, cultural divides between British officers and Indian troops, and territorial annexations.

Following Pandey’s mut!ny, numerous units of the Indian army swiftly joined peasant armies in a widespread revolt. The rebel forces, later joined by Indian nobility affected by the Doctrine of Lapse, saw the company as an intrusion into their traditional inheritance systems. Leaders like Nana Sahib and the Rani of Jhansi emerged from this group.

The rebellion, originating in Meerut, rapidly reached Delhi, capturing substantial portions of the North-Western Provinces and Awadh. In Awadh, the revolt assumed the character of a patriotic resistance against British presence. Despite the swift mobilization of the British East India Company, aided by friendly Princely states, it took until the end of 1858 to quell the rebellion. The poorly-equipped rebels, lacking external support, succumbed to br*tal suppression by the British.

Post-rebellion, authority shifted from the British East India Company to the British Crown. The Crown directly administered most of India as separate provinces. The British-controlled the company’s lands and exerted substantial indirect influence over the remaining territories, consisting of Princely states governed by local royal families. In 1947, during the nation’s independence, these princely states were absorbed into the newly formed nation, with only a few retaining state governments, including Mysore, Hyderabad, and Kashmir.

British Raj

The British Raj denotes the period of British Crown rule on the Indian subcontinent, also known as Crown rule in India or Direct rule in India, spanning from 1858 to 1947. In contemporary terms, the British-controlled region was referred to as India, encompassing territories directly administered by the United Kingdom, collectively termed British India, and regions ruled by native leaders under British paramountcy, known as the princely states. Although unofficially named the Indian Empire, it wasn’t the official designation.

Under the label “India,” the region played a significant role in international organizations, being a founding member of the League of Nations and actively participating in multiple Summer Olympics and the establishment of the United Nations in 1945.

Established on 28 June 1858, this governance system emerged after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, marking the transfer of authority from the British East India Company to the Crown, represented by Queen Victoria. This period continued until 1947, culminating in the partition of the British Raj into two independent dominion states: the Union of India, later becoming the Republic of India, and the Dominion of Pakistan, which eventually split into the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. The British Raj initially included Lower Burma, with Upper Burma added in 1886. In 1937, Burma became an autonomous province and gained independence in 1948, later renaming itself Myanmar in 1989.

Partition of India

The partition of India in 1947 marked the division of British India into two independent dominions: India, which is now the Republic of India, and Pakistan, comprising the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. This division was based on religious majorities in the provinces of Bengal and Punjab, resulting in significant demographic shifts. The partition affected various institutions, including the military, navy, air force, civil service, railways, and the central treasury, as outlined in the Indian Independence Act 1947. This event led to the end of the British Raj, or Crown rule in India, with the official establishment of the independent Dominions of India and Pakistan at midnight on 15 August 1947.

The partition caused a massive displacement of 10 to 20 million people along religious lines, constituting one of the largest refugee crises in history. The accompanying violence led to substantial loss of life, with estimates ranging from several hundred thousand to two million. The traumatic events during the partition generated a lasting atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan, impacting their relationship to the present day.

Republic of India

The history of independent India commenced on 15 August 1947 when the nation gained independence and became a sovereign nation within the British Commonwealth. British direct administration, initiated in 1858, contributed to the political and economic integration of the subcontinent. The conclusion of British rule in 1947 led to the partition of the subcontinent along religious lines, forming two distinct nations—India, predominantly Hindu, and Pakistan, predominantly Muslim. The partition triggered a significant population transfer, affecting over 10 million people between India and Pakistan and resulting in the tragic loss of about one million lives.

Jawaharlal Nehru, a leader of the Indian National Congress, assumed the role of the first Prime Minister of India, while Mahatma Gandhi, a pivotal figure in the independence struggle, chose not to hold any official position. The adoption of the constitution in 1950 established India as a democratic nation, a characteristic that has been maintained ever since. India’s enduring commitment to democratic principles stands out among the newly independent states worldwide.

India has grappled with challenges such as religious v!olence, c*steism, n*xalism, terror!sm, and regional separatist insurgenc!es. Territorial disputes persist, notably with China, leading to the Sino-Indian War in 1962, and with Pakistan, resulting in conflicts in 1947, 1965, 1971, and 1999. During the Cold War, India maintained neutrality and played a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement. However, a loose alliance was formed with the Soviet Union from 1971, a period when Pakistan aligned itself with the United States and the People’s Republic of China.