A team of archaeologists, led by British researchers, has discovered a vast collection of ancient art featuring mythical beings and gigantic creatures.

Located in a remote area of South America, the team has uncovered over a thousand ancient carvings, some of which are the largest examples of prehistoric rock art ever found. The archaeologists believe these findings represent only a small portion of what remains hidden, estimating that there could be up to 10,000 more engravings in the region, which covers an area of a thousand square miles—the size of Dorset.

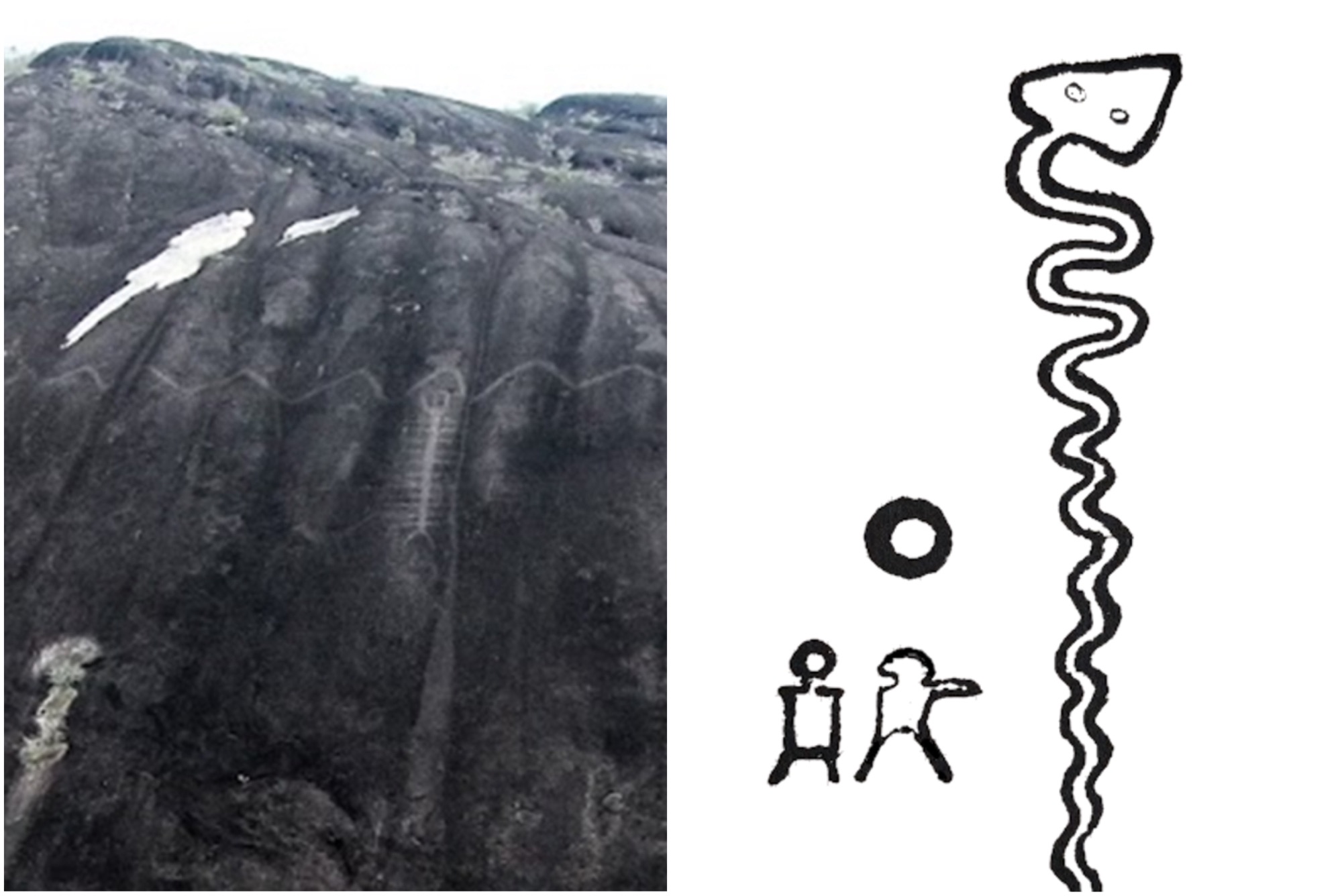

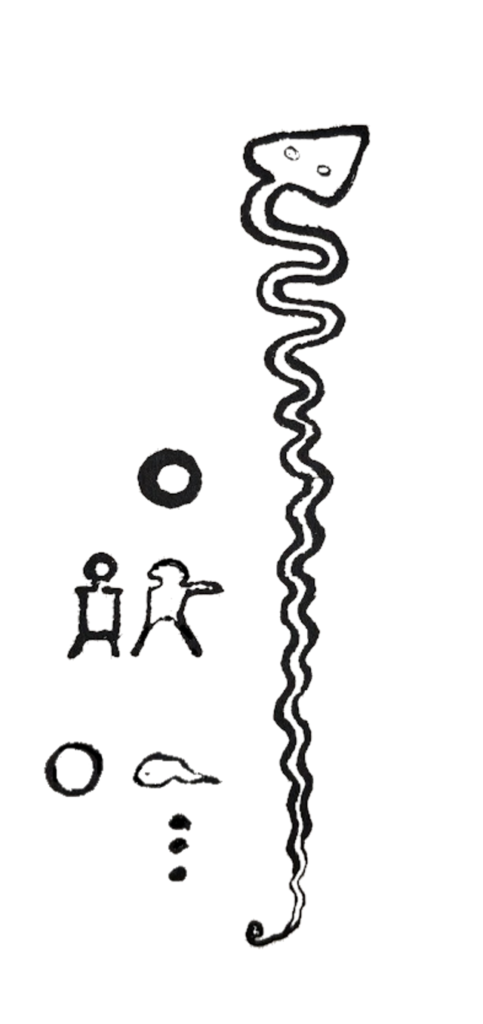

Among the most notable discoveries is a 43-meter-long depiction of a giant snake. Other carvings include oversized centipedes, massive animals, and towering human-like figures up to 10 meters tall.

These artworks, found near the Colombia-Venezuela border, depict a wide range of creatures, including stingrays, vultures, monkeys, crocodiles, dogs, jaguars, turtles, and frogs.

The site also includes numerous geometric carvings, such as concentric circles, grid patterns, and triangles filled with dots, whose meanings remain unknown. This site is one of the world’s largest collections of rock art, rivaling famous areas like France’s Dordogne, Italy’s Alpine north, Western Australia, and South Africa.

What distinguishes these engravings is their exceptional size; approximately 60 of the 1,000 discovered are over 10 meters in length. Notable examples include a 43-meter serpent, two 10-meter humanoid figures that may represent deities or shamans, an 11-meter centipede, and a likely four-meter insect, possibly depicting a butterfly.

Dr. Philip Riris from Bournemouth University’s archaeology and anthropology department has announced a significant discovery by his team in Colombia and Venezuela, revealing an ancient culture that had largely remained undocumented. This finding is expected to illuminate the artistic abilities and other achievements of a civilization that existed long before European colonization.

The discovery of seven massive snake engravings, ranging from 16 to 43 meters, is particularly notable as they may represent a global “mega-serpent” motif. Research suggests that serpent worship, or ophiolatry, was a prominent religious practice worldwide. This tradition is reflected in the mythologies and religious beliefs of various cultures, including those in ancient Europe, Egypt, Aboriginal Australia, and the Americas.

Mythologies from classical Greece to regions like the Middle East, Europe, Mexico, Africa, and Asia are rich with stories of serpentine deities and creatures, highlighting the widespread nature of snake worship in ancient times.

Throughout history, serpents have been venerated for their symbolic connections to human creation, immortality, and healing. Cultures worldwide have viewed them with a mix of reverence and fear, often attributing royal symbolism to them.

The widespread presence of serpent iconography in global mythology suggests that its origins are deeply rooted in human history, possibly dating back tens of thousands of years. This reverence is likely due to the significant threat snakes have posed to humans, second only to disease-carrying insects.

Annually, venomous snake bites cause approximately 20,000 deaths, far exceeding those caused by lions or crocodiles. Additionally, around 400,000 people suffer non-fatal snake bites each year. In the past, when human interaction with nature was more direct and constant, snakes represented a more pronounced danger, leading to their worship and placation.

This is evident in ancient depictions of serpents as immense beings, such as the monumental serpent carvings found in Colombia and Venezuela, and other massive serpent representations worldwide, including a 411-meter-long earthwork in southern Ohio that is around 900 years old.

The recent discovery of ancient engravings in Colombia, created by Native American artists around 700 to 1000 AD, represents some of the most challenging-to-access outdoor prehistoric art. These artists took on the dangerous task of carving into nearly vertical cliff faces, often located high above the ground.

For instance, a massive 43-meter serpent engraving is located on a cliff about 150 meters above the ground. It is believed that these and similar carvings served as oracles, allowing shamans to facilitate communication between the serpent and the local people, similar to the oracular traditions of ancient Greece and Egypt.

These engravings, numbering over a thousand, are distributed across 157 sites along a 177-kilometer stretch of the Orinoco River. The region was first explored by 16th-century European treasure hunters, including Sir Walter Raleigh, who sought the mythical gold of El Dorado but returned empty-handed. In contrast, contemporary archaeologists have uncovered a wealth of ancient art that promises to revolutionize our understanding of this long-forgotten culture.

Dr. Philip Riris hopes their research will help preserve the artistic legacy of the Orinoco valley and involve local communities in its protection. An article detailing these significant findings, authored by the project’s lead archaeologists, will be published in the journal Antiquity and available online for free.