Japan’s history dates back to the Paleolithic period, around 38,000 to 39,000 years ago, with the Jōmon people, who were hunter-gatherers, being the first inhabitants. Around the 3rd century BCE, the Yayoi people migrated to Japan, introducing iron technology and agriculture, which led to rapid population growth and the eventual dominance over the Jōmon. The earliest written reference to Japan appears in the Chinese Book of Han in the first century CE. Between the 4th and 9th centuries, Japan transitioned from a collection of tribes and kingdoms to a unified state under the Emperor, a dynasty that continues today in a ceremonial role.

The Heian period (794-1185) was a peak of classical Japanese culture and saw the integration of Shinto practices with Buddhism. Over time, the power of the imperial house waned, giving rise to aristocratic clans like the Fujiwara and samurai military clans. The Minamoto clan’s victory in the Genpei War (1180–85) led to the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate, marking the start of military rule under the shōgun. After the Kamakura shogunate fell in 1333, the Muromachi period followed, characterized by the growing power of regional warlords (daimyō) and civil war.

By the late 16th century, Japan was reunified by Oda Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The Tokugawa shogunate took over in 1600, initiating the Edo period, known for internal peace, a strict social hierarchy, and isolation from the outside world. European contact began with the Portuguese in 1543, who introduced firearms, followed by the American Perry Expedition in 1853-54, which ended Japan’s isolation. The Edo period ended in 1868, leading to the Meiji period, during which Japan modernized along Western lines and emerged as a great power.

Japan’s militarization escalated in the early 20th century, beginning with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and China in 1937. The attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 resulted in war with the United States and its allies. Despite severe losses from Allied bombings and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan only surrendered after the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on August 15, 1945. Japan was occupied by Allied forces until 1952, during which a new constitution was enacted, transforming the country into a constitutional monarchy.

Following the occupation, Japan experienced rapid economic growth, particularly after 1955 under the Liberal Democratic Party’s leadership, becoming a global economic powerhouse. However, growth has slowed since the economic stagnation of the “Lost Decade” in the 1990s. Japan remains a significant global player, balancing its rich cultural heritage with modern achievements.

The Prehistoric Era of Japan

Hunter-gatherers first arrived in Japan during the Paleolithic period, around 38,000 to 40,000 years ago. Due to Japan’s acidic soils, which are not conducive to fossilization, little physical evidence of their presence remains. However, unique edge-ground axes dated to over 30,000 years ago suggest the arrival of the first Homo sapiens in the archipelago. Early humans are believed to have reached Japan by sea, using watercraft. Evidence of human habitation has been found at specific sites, including 32,000 years ago in Okinawa’s Yamashita Cave and 20,000 years ago in Ishigaki Island’s Shiraho Saonetabaru Cave.

Jōmon Era

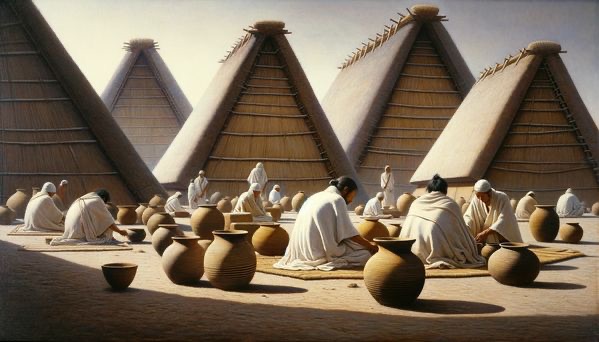

The Jōmon Period in Japan, spanning from around 14,000 to 300 BCE, was a significant era marked by a hunter-gatherer and early agriculturalist society, developing into a notably complex and sedentary culture. One of its most distinctive features is the “cord-marked” pottery, among the world’s oldest, discovered by American zoologist and orientalist Edward S. Morse in 1877.

The Jōmon Period is divided into several phases:

- Incipient Jōmon (13,750-8,500 BCE)

- Initial Jōmon (8,500-5,000 BCE)

- Early Jōmon (5,000-3,520 BCE)

- Middle Jōmon (3,520-2,470 BCE)

- Late Jōmon (2,470-1,250 BCE)

- Final Jōmon (1,250-500 BCE)

Each phase reflects significant regional and temporal diversity. During the early Jōmon Period, the Japanese archipelago was connected to continental Asia, but rising sea levels around 12,000 BCE led to its isolation. The Jōmon population primarily inhabited Honshu and Kyushu, areas rich in seafood and forest resources. The Early Jōmon saw a population surge due to the warm and humid Holocene climatic optimum, but by 1500 BCE, as the climate cooled, the population declined. Various forms of horticulture and small-scale agriculture existed throughout the Jōmon Period, though the extent remains debated.

The Final Jōmon phase marked a pivotal transition. Around 900 BCE, increased contact with the Korean Peninsula led to the emergence of new farming cultures, including the Yayoi period between 500 and 300 BCE. In Hokkaido, traditional Jōmon culture evolved into the Okhotsk and Epi-Jōmon cultures by the 7th century, signifying a gradual assimilation of new technologies and cultures, such as wet rice farming and metallurgy, into the Jōmon framework.

Yayoi Era

The Yayoi people arrived from the Asian mainland between 1,000 and 800 BCE, bringing significant changes to the Japanese archipelago. They introduced new technologies, such as rice cultivation and metallurgy, initially imported from China and the Korean Peninsula. Originating from northern Kyūshū, the Yayoi culture gradually replaced the indigenous Jōmon people, resulting in some genetic mixing between the two. This period also saw the introduction of weaving, silk production, new woodworking techniques, glassmaking, and new architectural styles.

Scholars continue to debate whether these changes were primarily due to migration or cultural diffusion, though genetic and linguistic evidence tends to support migration. Historian Hanihara Kazurō estimates that annual immigration ranged from 350 to 3,000 people. As a result, Japan’s population surged, possibly increasing tenfold compared to the Jōmon period, with estimates of the population reaching between 1 and 4 million by the end of the Yayoi period. Skeletal remains from the late Jōmon period indicate declining health standards, while Yayoi sites suggest improved nutrition and societal structures, including grain storehouses and military fortifications.

During the Yayoi era, tribes began to form various kingdoms. The Book of Han, published in 111 CE, mentions that Japan, referred to as Wa, was composed of one hundred kingdoms. By 240 CE, according to the Book of Wei, the kingdom of Yamatai, led by the female monarch Himiko, had gained prominence. The exact location of Yamatai and other details remain subjects of debate among historians.

Kofun Era

The Kofun period, spanning approximately 300 to 538 CE, represents a pivotal era in Japan’s historical and cultural evolution. This period is notable for its keyhole-shaped burial mounds, known as “kofun,” and is recognized as the earliest period of recorded history in Japan. The Yamato clan rose to prominence during this time, especially in southwestern Japan, where they centralized political authority and began to develop a structured administration influenced by Chinese models. While various local powers, such as Kibi and Izumo, maintained some autonomy, by the 6th century, the Yamato clans began to dominate southern Japan.

During the Kofun period, society was led by powerful clans (gōzoku), each headed by a patriarch who performed sacred rituals for the clan’s welfare. The Yamato court, controlled by the royal line, was at its peak, and clan leaders were granted “kabane,” hereditary titles indicating rank and political standing. The Yamato polity was not a singular rule, as other regional chieftainships, such as Kibi, were strong contenders for power during the first half of the Kofun period.

Cultural influences flowed between Japan, China, and the Korean Peninsula, evidenced by wall decorations and Japanese-style armor found in Korean burial mounds. Buddhism and the Chinese writing system were introduced to Japan from Baekje near the end of the Kofun period. Despite the Yamato’s centralizing efforts, other powerful clans like the Soga, Katsuragi, Heguri, and Koze played significant roles in governance and military activities.

The Yamato expanded their territorial influence during this period, with several frontiers being recognized. Legends, such as that of Prince Yamato Takeru, suggest the existence of rival entities and battlegrounds in regions like Kyūshū and Izumo. The period also saw an influx of immigrants from China and Korea, who made substantial contributions to Japan’s culture, governance, and economy. Clans like the Hata and Yamato-Aya, consisting of Chinese immigrants, held significant influence, particularly in financial and administrative roles.

CLASSICAL JAPAN

Asuka Era

The Asuka period in Japan began around 538 CE with the introduction of Buddhism from the Korean kingdom of Baekje. This era was named after its de facto imperial capital, Asuka. During this time, Buddhism coexisted with the native Shinto religion in a fusion known as Shinbutsu-shūgō. The Soga clan, who supported Buddhism, took control of the government in the 580s and ruled indirectly for about sixty years. Prince Shōtoku, serving as regent from 594 to 622, played a crucial role in the period’s development. He authored the Seventeen-article constitution, based on Confucian principles, and introduced a merit-based civil service system called the Cap and Rank System.

In 645, Prince Naka no Ōe and Fujiwara no Kamatari overthrew the Soga clan in a coup, leading to significant administrative changes known as the Taika Reforms. These reforms, inspired by Confucian ideologies from China, aimed to nationalize all land for equitable distribution among cultivators and called for the creation of a household registry for taxation. The goal was to centralize power and strengthen the imperial court, drawing heavily from Chinese governmental structures. Envoys and students were sent to China to study various aspects including writing, politics, and art.

Following the Taika Reforms, the Jinshin War of 672 occurred, a conflict between Prince Ōama and his nephew Prince Ōtomo, both vying for the throne. This war led to further administrative changes, culminating in the Taihō Code. The Taihō Code consolidated existing laws and outlined the structure of central and local governments, leading to the establishment of the Ritsuryō State, a system of centralized government modeled after China that lasted for approximately five centuries.

Nara Period

The Nara period in Japan, lasting from 710 to 794 CE, was a transformative era. The capital was initially established in Heijō-kyō (now Nara) by Empress Genmei and remained the center of Japanese civilization until it moved to Nagaoka-kyō in 784 and then to Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto) in 794. This period saw the centralization and bureaucratization of governance, inspired by China’s Tang dynasty. Chinese influences were evident in various areas, including writing systems, art, and Buddhism. Japanese society during this time was primarily agrarian, centered around village life, and largely followed Shintō.

Significant developments occurred in government bureaucracy, economic systems, and culture, including the compilation of important works like the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki. Despite efforts to strengthen central governance, the period experienced factional strife within the imperial court, leading to notable decentralization by its end. External relations included complex interactions with the Chinese Tang dynasty, a strained relationship with the Korean kingdom of Silla, and the subjugation of the Hayato people in southern Kyushu. The Nara period laid the foundation for Japanese civilization but concluded with the capital’s shift to Heian-kyō in 794 CE, marking the beginning of the Heian period.

A key feature of this period was the establishment of the Taihō Code, which led to significant reforms and the creation of a permanent imperial capital in Nara. However, the capital moved several times due to rebellions and political instability before finally returning to Nara. The city flourished as Japan’s first true urban center, with a population of 200,000 and significant economic and administrative activities.

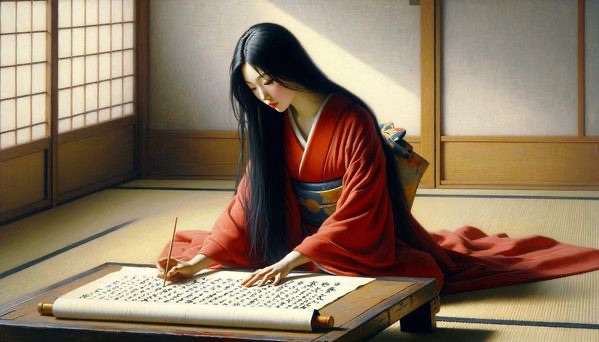

Culturally, the Nara period was rich and formative, seeing the production of Japan’s first significant literary works, such as the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, which served to justify and establish the supremacy of the emperors. Poetry also flourished, most notably with the compilation of the Man’yōshū, the largest and longest-lasting collection of Japanese poetry.

The period also saw the establishment of Buddhism as a significant religious and cultural force. Emperor Shōmu and his consort were fervent Buddhists who actively promoted the religion, building temples across the provinces. Buddhism began to wield considerable influence at court, especially during the reigns of Empress Kōken and later, Empress Shōtoku.

Despite its achievements, the Nara period faced challenges, including factional fighting and power struggles, leading to instability. Financial burdens prompted decentralization measures. In 784, the capital moved to Nagaoka-kyō to regain imperial control, and in 794, it moved again to Heian-kyō, marking the end of the Nara period and the beginning of a new chapter in Japanese history.

Heian Era

The Heian period in Japan, spanning from 794 to 1185 CE, commenced with the relocation of the capital to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). Political power initially shifted to the Fujiwara clan, who solidified their influence through strategic marriages with the imperial family. A smallpox epidemic from 812 to 814 CE drastically reduced the population, killing nearly half of the Japanese people. By the late 9th century, the Fujiwara clan had firmly established their control.

Fujiwara no Yoshifusa became sesshō (regent) to a young emperor in 858, and his son Fujiwara no Mototsune later created the office of kampaku, effectively ruling on behalf of adult emperors. The Fujiwara clan reached the peak of their power under Fujiwara no Michinaga, who became kampaku in 996 and arranged marriages between his daughters and the imperial family. This dominance lasted until 1086 when Emperor Shirakawa introduced the practice of cloistered rule.

As the Heian period progressed, the imperial court’s authority weakened. Focused on internal power struggles and artistic endeavors, the court neglected governance beyond the capital, leading to the decline of the ritsuryō state. Tax-exempt shōen manors, owned by noble families and religious orders, emerged and controlled more land than the central government by the 11th century, depriving it of revenue and fostering the creation of private samurai armies.

The early Heian period also saw efforts to consolidate control over the Emishi people in northern Honshu. The title of seii tai-shōgun was granted to military commanders who successfully subdued these indigenous groups. However, this control was challenged in the mid-11th century by the Abe clan, leading to wars and a temporary reassertion of central authority in the north.

In the late Heian period, around 1156, a succession dispute led to military involvement by the Taira and Minamoto clans. This conflict culminated in the Genpei War (1180–1185), resulting in the Taira clan’s defeat and the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate under Minamoto no Yoritomo, effectively shifting power away from the imperial court.

FEUDAL JAPAN

Kamakura Period

After the Genpei War and the consolidation of power by Minamoto no Yoritomo, the Kamakura Shogunate was established in 1192 when Yoritomo was declared seii tai-shōgun by the Imperial Court in Kyoto. This government, known as the bakufu, held power authorized by the Imperial court, which retained its bureaucratic and religious functions. The shogunate functioned as the de facto government of Japan while keeping Kyoto as the official capital. This collaborative power structure differed from the more straightforward warrior rule that characterized the later Muromachi period.

Family dynamics significantly influenced the governance of the shogunate. Yoritomo was suspicious of his brother Yoshitsune, who sought refuge in northern Honshu under the protection of Fujiwara no Hidehira. After Hidehira’s death in 1189, his successor Yasuhira attacked Yoshitsune to gain Yoritomo’s favor. Yoshitsune was killed, and Yoritomo subsequently conquered the Northern Fujiwara territories. Yoritomo’s death in 1199 led to a decline in the shogun’s office and a rise in power for his wife Hōjō Masako and her father Hōjō Tokimasa. By 1203, the Minamoto shoguns had effectively become puppets under the Hōjō regents.

The Kamakura regime was feudalistic and decentralized, contrasting with the earlier centralized ritsuryō state. Yoritomo selected provincial governors, known as shugo or jitō, from his close vassals, the gokenin. These vassals maintained their own armies and administered their provinces autonomously. However, in 1221, a failed rebellion known as the Jōkyū War, led by the retired Emperor Go-Toba, attempted to restore power to the imperial court but instead resulted in the shogunate consolidating even more power over the Kyoto aristocracy.

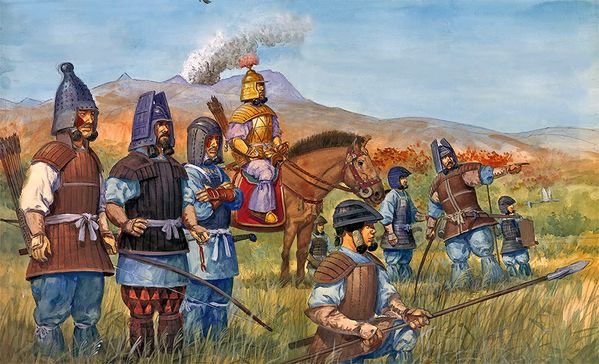

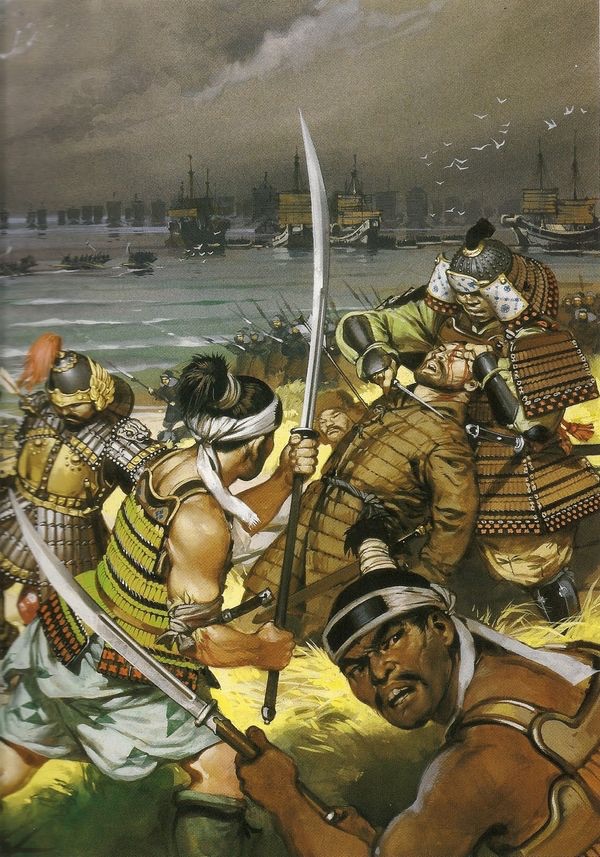

The Kamakura shogunate faced invasions from the Mongol Empire in 1274 and 1281. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the shogunate’s samurai armies resisted the Mongol invasions, aided by typhoons that destroyed the Mongol fleets. However, the financial strain of these defenses weakened the shogunate’s relationship with the samurai class, who felt inadequately rewarded for their contributions to the victories. This discontent among the samurai contributed to the overthrow of the Kamakura shogunate. In 1333, Emperor Go-Daigo launched a rebellion to restore full power to the imperial court. The shogunate sent General Ashikaga Takauji to quell the revolt, but Takauji and his men joined forces with Emperor Go-Daigo and overthrew the Kamakura shogunate.

Amid these military and political events, Japan experienced social and cultural growth starting around 1250. Advances in agriculture, improved irrigation techniques, and double-cropping led to population growth and the development of rural villages. Cities grew, and commerce boomed due to fewer famines and epidemics. Buddhism became more accessible to the common people, with the establishment of Pure Land Buddhism by Hōnen and Nichiren Buddhism by Nichiren. Zen Buddhism also gained popularity among the samurai class. Despite the turbulent politics and military challenges, the period was one of significant growth and transformation for Japan.

Muromachi Era

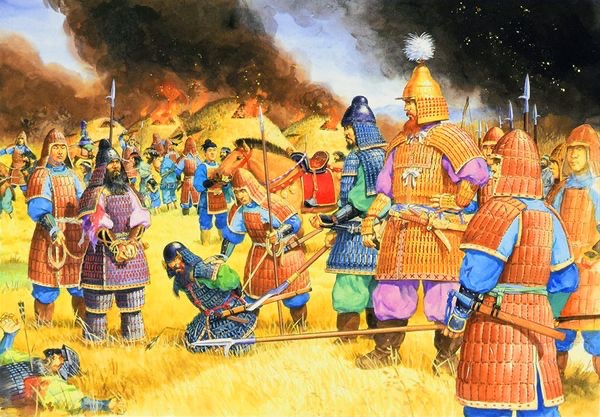

In 1333, Emperor Go-Daigo initiated a revolt to reclaim authority for the imperial court. Initially supported by General Ashikaga Takauji, their alliance fell apart when Go-Daigo refused to appoint Takauji as shōgun. Takauji turned against the Emperor in 1338, seized Kyoto, and installed a rival, Emperor Kōmyō, who appointed him shōgun. Go-Daigo fled to Yoshino, establishing a rival Southern Court, leading to a prolonged conflict with the Northern Court set up by Takauji in Kyoto. The Shogunate faced ongoing challenges from regional lords, called daimyōs, who became increasingly autonomous.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, Takauji’s grandson, took power in 1368 and successfully consolidated shogunate power, ending the civil war between the Northern and Southern Courts in 1392. However, by 1467, Japan entered another tumultuous period with the Ōnin War, stemming from a succession dispute. The country fragmented into hundreds of independent states ruled by daimyōs, diminishing the shogun’s power. Daimyōs battled each other for control over different parts of Japan, with prominent figures such as Uesugi Kenshin and Takeda Shingen. Insurrectionist peasants and “warrior monks” affiliated with Buddhist temples also formed their own military forces.

During this Warring States period, the first Europeans, Portuguese traders, arrived in Japan in 1543, introducing firearms and Christianity. By 1556, daimyōs were using about 300,000 muskets, and Christianity gained a significant following. Portuguese trade was initially welcomed, with cities like Nagasaki becoming bustling trade hubs under the protection of Christian daimyōs. Warlord Oda Nobunaga capitalized on European technology to gain power, initiating the Azuchi–Momoyama period in 1573.

Despite the internal conflicts, Japan experienced economic prosperity that began during the Kamakura period. By 1450, Japan’s population reached ten million, and commerce flourished, including significant trade with China and Korea. This era also saw the development of iconic Japanese art forms such as ink wash painting, ikebana, bonsai, Noh theater, and the tea ceremony. Although plagued by ineffective leadership, the period was culturally rich, with landmarks like Kyoto’s Kinkaku-ji, the “Temple of the Golden Pavilion,” being built in 1397.

Azuchi Momoyama Era

During the latter part of the 16th century, Japan experienced significant changes towards unity led by two powerful warlords, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. This period, known as the Azuchi–Momoyama era, marked the final phase of the Sengoku Period from 1568 to 1600. Nobunaga, hailing from Owari, rose to prominence in 1560 after defeating Imagawa Yoshimoto at Okehazama. He was a strategic and ruthless leader who modernized his army, rewarded talent over social status, and adopted Christianity to forge alliances and provoke Buddhist adversaries.

Nobunaga’s efforts for unity were thwarted in 1582 when he was betrayed and killed by Akechi Mitsuhide. Hideyoshi, a former servant turned general under Nobunaga, avenged his master’s death and completed the unification by overcoming opposition in various regions. Hideyoshi implemented sweeping reforms like confiscating swords from peasants, restricting daimyōs, and categorizing cultivators as “commoners,” thereby freeing most slaves.

Hideyoshi’s ambitions extended beyond Japan to China, leading unsuccessful invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. Following his death in 1598, internal strife erupted in Japan, culminating in Tokugawa Ieyasu’s victory at Sekigahara in 1600, ending the Toyotomi rule and establishing the Tokugawa shogunate, which lasted until 1868. This transformative period also witnessed administrative changes to boost trade, stabilize society, and set the stage for the Edo Period.

Edo Era

The Edo Period, spanning from 1603 to 1868, characterized a time of stability, peace, and cultural advancement in Japan during the Tokugawa Shogunate. This era commenced with Emperor Go-Yōzei appointing Tokugawa Ieyasu as shōgun, centralizing power in Edo (now Tokyo) through policies like the Laws for the Military Houses and the alternate attendance system to govern the daimyōs. Despite these efforts, daimyōs maintained significant autonomy within their territories, while the shogunate enforced a strict social hierarchy with samurai at the apex as administrators and the emperor in Kyoto as a symbolic figure.

To curb unrest, the shogunate imposed severe penalties for minor infractions, particularly targeting Christians, culminating in the prohibition of Christianity after the Shimabara Rebellion in 1638. Embracing isolation through sakoku, Japan limited foreign interactions to the Dutch, Chinese, and Koreans, restricting Japanese citizens from overseas travel. This isolationist stance bolstered the Tokugawa’s authority but isolated Japan from external influences for over two centuries.

Notwithstanding isolation, the Edo era witnessed agricultural and commercial expansion, fueling a population surge as literacy and numeracy rates climbed. Government projects and currency standardization fostered economic growth, benefiting both rural and urban residents. While the majority lived in rural areas, cities like Edo experienced significant population growth.

Culturally, the period was a hotbed of creativity, with the emergence of the “floating world” concept, ukiyo-e prints, kabuki and bunraku theater, and haiku poetry. Neo-Confucianism influenced societal stratification into four classes, based on occupations. The shogunate’s decline from the late 18th century was catalyzed by economic woes, discontent among social classes, and challenges like the Tenpō famines. Encounters with Western powers, beginning with Commodore Perry in 1853, led to unequal treaties, internal unrest, and ultimately, the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868, ushering in the Meiji Restoration.

MODERN JAPAN

Meiji Era

The Meiji Restoration, commencing in 1868, marked a significant shift in Japanese history, propelling Japan towards modernization as a nation-state. Spearheaded by Meiji leaders such as Ōkubo Toshimichi and Saigō Takamori, the government aimed to emulate Western powers. Fundamental changes included replacing the feudal Edo class system with prefectures, integrating Western technologies like railways and telegraphs, and establishing a universal education system.

A comprehensive modernization initiative by the Meiji government transformed Japan into a Western-style nation-state. Key reforms encompassed the dissolution of the feudal class structure, the creation of a prefectural system, and extensive tax restructuring. Christianity bans were lifted, Western technologies like railways and telegraphs were adopted, and a universal education system was introduced. Western consultants were enlisted to modernize education, finance, and the military.

Advocates like Fukuzawa Yukichi championed Westernization, prompting societal shifts like adopting the Gregorian calendar and Western attire. Scientific advancements, notably in medical science, emerged during this era, with figures like Kitasato Shibasaburō founding the Institute for Infectious Diseases in 1893 and Hideyo Noguchi linking syphilis to paresis in 1913. Literary movements flourished with authors such as Natsume Sōseki and Ichiyō Higuchi blending European and Japanese literary styles.

The Meiji government encountered internal political obstacles, notably the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement demanding greater civic involvement. Itō Hirobumi drafted the Meiji Constitution in response, unveiled in 1889, establishing a partially elected House of Representatives. The emperor retained a central role, with direct military and cabinet reporting. Nationalism surged, with Shinto designated as the state religion and schools fostering allegiance to the emperor.

Japan’s military played a crucial role in fulfilling its foreign policy aims, engaging in conflicts like the Mudan Incident and the Satsuma Rebellion. Victories in the First Sino-Japanese War against China and the Russo-Japanese War against Russia bolstered Japan’s stature, leading to territorial gains and global recognition. Industrialization surged, with zaibatsus like Mitsubishi and Sumitomo dominating, driving urbanization and transforming Japan into a modern industrialized nation by the end of the Meiji era.

Taishō period

The Taishō period, spanning from 1912 to 1926, was characterized by significant political, social, and economic changes in Japan. Following the death of Emperor Meiji, Emperor Taishō ascended to the throne, and his reign was marked by Japan’s continued modernization and a shift towards more democratic governance.

During this era, Japan experienced the “Taishō democracy,” where political power began to shift from the oligarchs of the Meiji era to the elected members of the Diet. This period saw the rise of political parties and increased participation in government by the Japanese populace. The implementation of universal male suffrage in 1925 was a significant milestone, reflecting the period’s democratic aspirations.

Economically, the Taishō period witnessed substantial growth and industrialization. Japan emerged as a global economic power, benefiting from World War I’s economic boom and expanding its influence in Asia. The period also saw significant urbanization, with more people moving to cities for employment in the growing industrial sector.

Culturally, the Taishō period was marked by the flourishing of arts and literature. Western influences became more pronounced, and there was a blending of Western and traditional Japanese styles in various forms of artistic expression. This era also saw the rise of a more liberal and cosmopolitan urban culture, particularly in cities like Tokyo and Osaka.

However, the Taishō period was not without its challenges. Political instability, economic fluctuations, and social unrest were prevalent, culminating in events like the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, which devastated Tokyo and Yokohama. Despite these challenges, the Taishō period remains a significant chapter in Japan’s history, representing a time of transformation and modernization.

Shōwa Era

The Shōwa period, spanning from 1926 to 1989, was a time of profound transformation in Japan. It began with the ascension of Emperor Hirohito to the throne and encompassed some of the most turbulent and transformative years in Japanese history.

The early years of the Shōwa period were marked by militarization and imperial expansion. Japan’s aggressive military campaigns in Asia led to the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. These actions contributed to the outbreak of World War II, with Japan joining the Axis powers and attacking Pearl Harbor in 1941. The war ended in 1945 with Japan’s defeat and the devastating atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Post-war, Japan underwent significant reconstruction and reform under Allied occupation. The new constitution, enacted in 1947, transformed Japan into a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary government, renouncing war and emphasizing human rights. This period also saw the dismantling of Japan’s military-industrial complex and the establishment of democratic institutions.

Economically, the Shōwa period witnessed Japan’s remarkable recovery and growth. From the 1950s to the 1980s, Japan experienced rapid industrialization and became one of the world’s leading economic powers. This era, often referred to as the “Japanese economic miracle,” saw advancements in technology, manufacturing, and infrastructure. The Tokyo Olympics in 1964 symbolized Japan’s recovery and international re-emergence.

Culturally, the Shōwa period was a time of significant change and modernization. Western influences permeated Japanese society, blending with traditional customs. The period saw the rise of a consumer culture, advancements in education, and developments in arts and entertainment. Japanese cinema, literature, and popular culture gained international acclaim, with figures like Akira Kurosawa and Haruki Murakami becoming prominent.

However, the Shōwa period also faced challenges such as political instability, economic bubbles, and social changes. The 1970s and 1980s saw economic challenges that culminated in the burst of the asset price bubble in the early 1990s, leading to a prolonged economic stagnation known as the “Lost Decade.”

Overall, the Shōwa period was a defining era for Japan, characterized by its dramatic shifts from militarism to democracy, economic hardship to prosperity, and traditionalism to modernity.

Heisei Era

The Heisei period, lasting from 1989 to 2019, marked significant transitions and challenges for Japan. It began with the ascension of Emperor Akihito to the throne following the death of Emperor Hirohito.

The early Heisei years were characterized by the burst of Japan’s economic bubble in the early 1990s, leading to a prolonged period of economic stagnation known as the “Lost Decade.” This era saw Japan struggling with deflation, a banking crisis, and slow economic growth, affecting its previously robust economy.

Despite economic challenges, the Heisei period also witnessed advancements in technology and infrastructure. Japan continued to be a global leader in electronics, automotive manufacturing, and robotics. The country also hosted significant international events, including the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano.

Socially, the Heisei period experienced significant changes. Japan faced an aging population and low birth rates, leading to concerns about the sustainability of its social welfare systems. The government implemented various reforms to address these issues, including efforts to increase women’s participation in the workforce and improve childcare support.

Natural disasters marked the Heisei period as well. The 1995 Kobe earthquake caused extensive damage and loss of life, prompting improvements in disaster preparedness and response. The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, followed by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, were particularly devastating, leading to widespread destruction and a re-evaluation of Japan’s energy policies.

Culturally, the Heisei period saw Japan maintaining its rich traditions while also embracing modern influences. Japanese pop culture, including anime, manga, and video games, gained global popularity. The period also saw advancements in arts and literature, with Japanese authors and filmmakers receiving international recognition.

Politically, Japan navigated through several changes in leadership and policies. The government focused on economic reforms, international trade agreements, and strengthening diplomatic relationships. Japan also played a significant role in global organizations and peacekeeping missions.

Overall, the Heisei period was a time of economic recovery, social change, and resilience in the face of natural disasters. It laid the groundwork for future developments as Japan entered the Reiwa era with Emperor Naruhito’s ascension in 2019.

Reiwa Era

The Reiwa period began in 2019 with the ascension of Emperor Naruhito to the throne, following the abdication of his father, Emperor Akihito. This era marks a new chapter for Japan, focusing on harmony and new beginnings.

Economically, the Reiwa period has been characterized by efforts to revive Japan’s economy amidst global challenges, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The government has implemented measures to stimulate growth, support businesses, and manage public health. The pandemic has also accelerated digital transformation and highlighted the need for innovation in various sectors.

Socially, Japan continues to address issues such as an aging population and declining birth rates. Efforts to increase women’s participation in the workforce and improve work-life balance remain priorities. The government is also focusing on enhancing social welfare systems and healthcare to support the elderly population.

Environmentally, Japan is making strides towards sustainability and renewable energy. The country has committed to reducing carbon emissions and investing in green technologies to combat climate change. The aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster continues to influence Japan’s energy policies, with a shift towards safer and more sustainable energy sources.

Culturally, the Reiwa period embraces both tradition and modernity. Japan continues to promote its cultural heritage while fostering contemporary arts, literature, and technology. The global popularity of Japanese pop culture, including anime, manga, and video games, remains strong.

Politically, Japan is navigating through domestic and international challenges. The government is working on economic reforms, international trade agreements, and strengthening diplomatic relationships. Japan aims to play an active role in global organizations and contribute to international peace and stability.

Overall, the Reiwa period is marked by a focus on harmony, resilience, and innovation. Japan is striving to address its socio-economic challenges, promote sustainability, and maintain its cultural heritage while adapting to a rapidly changing world.