Iraq, historically known as Mesopotamia, is recognized as one of the world’s oldest civilizations, with roots tracing back to 6000-5000 BCE during the Neolithic Ubaid period. This region served as the foundation for several ancient empires, including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Neo-Sumerians, Babylonians, Neo-Assyrians, and Neo-Babylonians. Often referred to as the cradle of early writing, literature, science, mathematics, law, and philosophy, Mesopotamia saw the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire to the Achaemenid Empire in 539 BCE.

Following this, Iraq came under the influence of Greek, Parthian, and Roman powers. The region experienced significant Arab migration and saw the establishment of the Lakhmid Kingdom around 300 CE, during which the Arabic name al-ʿIrāq began to take shape. The Sassanid Empire eventually fell to the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century. Baghdad, founded in 762, emerged as a pivotal Abbasid capital and a major cultural hub during the Islamic Golden Age.

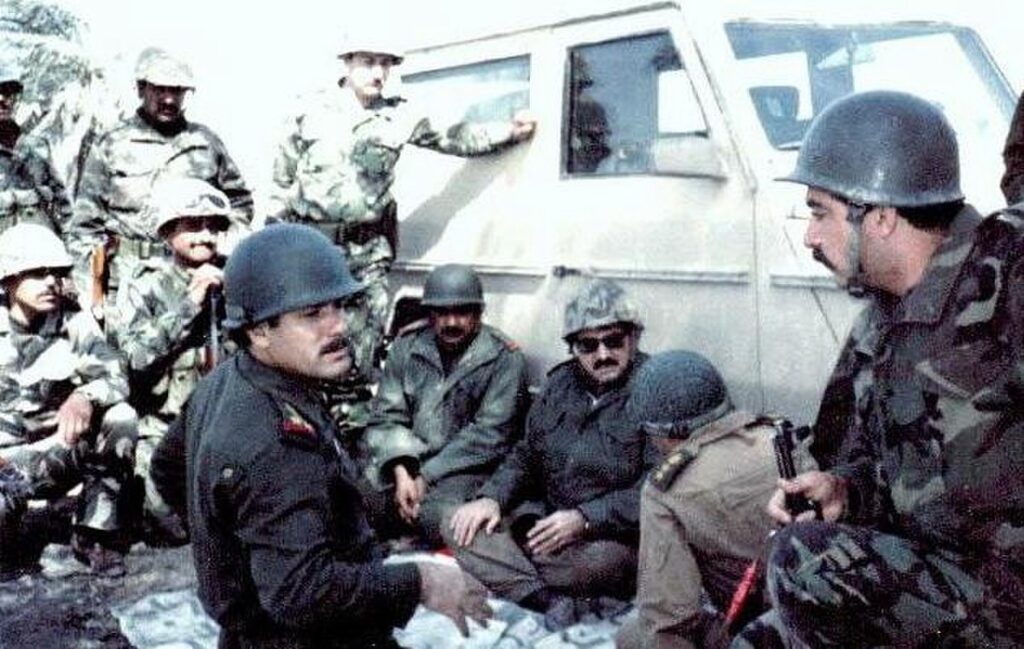

After the Mongol invasion in 1258, Iraq’s prominence diminished under various rulers until it became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. Following World War I, Iraq was placed under British mandate and later established as a kingdom in 1932. A republic was formed in 1958, leading to the rule of Saddam Hussein from 1968 to 2003. This period was marked by the Iran-Iraq War and the Gulf War, culminating in the 2003 U.S. invasion.

2000000 BCE – 5500 BCEPREHISTORY

17000 BCE JAN 1 – 10000 BCE

PALAEOLITHIC PERIOD OF MESOPOTAMIA

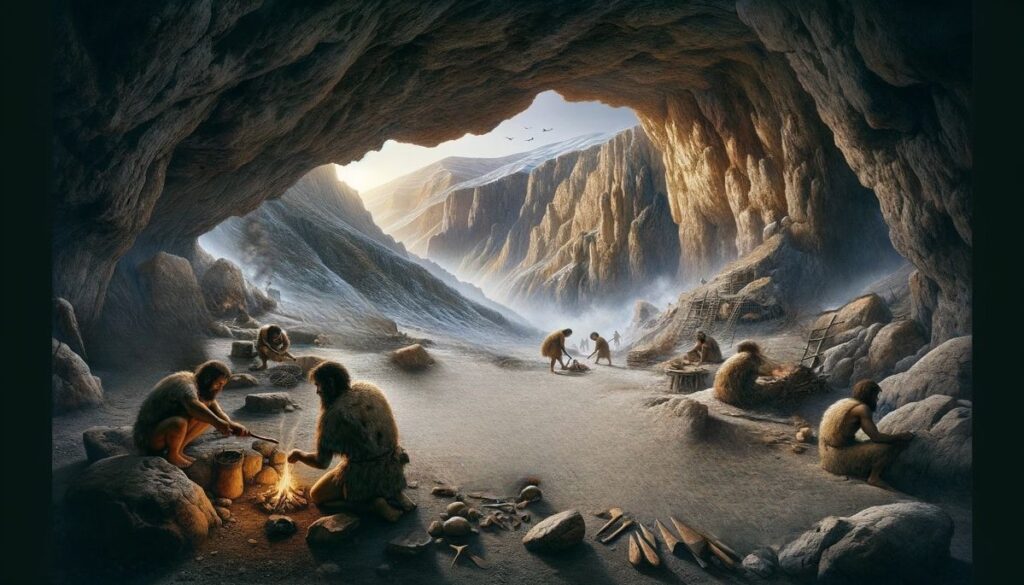

Shanidar Cave, Goratu, Iraq

The prehistory of Mesopotamia, extending from the Paleolithic era to the advent of writing in the Fertile Crescent, includes areas surrounding the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the Zagros foothills, southeastern Anatolia, and northwestern Syria. This era remains poorly documented, particularly in southern Mesopotamia before the 4th millennium BCE, primarily due to geological conditions that have buried many artifacts beneath alluvium or submerged them in the Persian Gulf.

During the Middle Paleolithic period, hunter-gatherers inhabited the Zagros caves and open-air sites, crafting Mousterian lithic tools. Notably, funerary remains discovered in Shanidar Cave reveal practices of solidarity and care among these communities.

In the Upper Paleolithic era, modern humans in the Zagros region employed bone and antler tools, a characteristic of the local Aurignacian culture referred to as “Baradostian.”

The late Epipaleolithic period, approximately 17,000-12,000 BCE, is marked by the Zarzian culture and the establishment of temporary villages featuring circular structures. The presence of fixed objects, such as millstones and pestles, indicates the early stages of sedentarization.

Between the 11th and 10th millennia BCE, the first sedentary hunter-gatherer villages began to emerge in northern Iraq. These settlements included houses arranged around a central “hearth,” suggesting a form of family property. Evidence of preserved skulls and artistic depictions of birds of prey provide insights into the cultural practices of this time.

10000 BCE JAN 1 – 6500 BCE

PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC PERIOD OF MESOPOTAMIA

Dağeteği, Göbekli Tepe, Halili

The early Neolithic human settlement in Mesopotamia, similar to the preceding Epipaleolithic period, was primarily located in the foothill regions of the Taurus and Zagros Mountains, as well as the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) period, spanning from 10,000 to 8,700 BCE, marked the advent of agriculture, while the earliest evidence of animal domestication emerged during the transition from the PPNA to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) around the end of the 9th millennium BCE. This era, known as the cradle of civilization, witnessed the rise of agricultural practices, hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were interred beneath the floors of homes.

Agriculture became the cornerstone of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Mesopotamia. The domestication of crops like wheat and barley led to the establishment of permanent settlements. This shift is evidenced by sites such as Abu Hureyra and Mureybet, which were occupied from the Natufian period into the PPNB. Additionally, the earliest monumental sculptures and circular stone structures from Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, dating to the PPNA/Early PPNB, showcase the collaborative efforts of a large community of hunter-gatherers.

Jericho, a notable settlement from the PPNA period, is often considered the world’s first town, emerging around 9,000 BCE. It housed a population of 2,000 to 3,000 people, protected by a substantial stone wall and tower. The purpose of this wall remains a subject of debate, as there is no clear evidence of significant warfare during this time. Some theories suggest it was built to protect Jericho’s valuable salt resources, while others propose that the tower was aligned with the shadow of a nearby mountain during the summer solstice, symbolizing power and reinforcing the town’s ruling hierarchy.

6500 BCE JAN 1

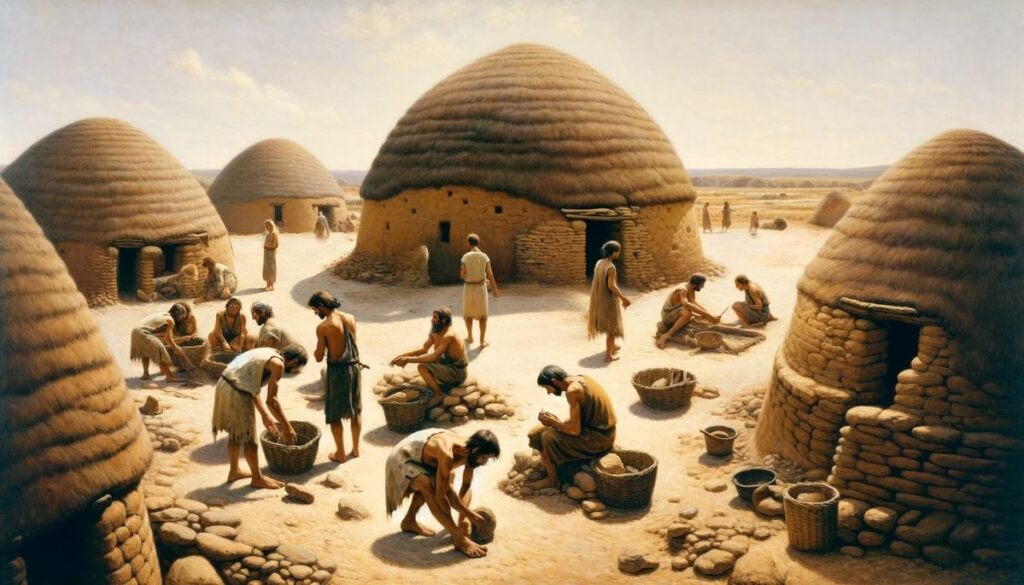

POTTERY NEOLITHIC PERIOD OF MESOPOTAMIA

Mesopotamia, Iraq

The 7th and 6th millennia BCE marked the rise of significant ceramic cultures in Mesopotamia, particularly the Hassuna, Samarra, and Halaf cultures. These societies were defined by the definitive adoption of agriculture and animal husbandry, fundamentally altering the economic landscape. Architecturally, there was a transition toward more complex structures, including large communal dwellings centered around collective granaries. The development of irrigation systems represented a major technological advancement essential for supporting agricultural practices. Cultural dynamics varied among these groups; the Samarra culture exhibited signs of social inequality, while the Halaf culture seemed to consist of smaller, less hierarchical communities.

Simultaneously, the Ubaid culture began to emerge in southern Mesopotamia toward the end of the 7th millennium BCE, with Tell el-’Oueili recognized as its oldest known site. The Ubaid culture is notable for its advanced architecture and the implementation of irrigation, a crucial innovation in a region where agriculture relied heavily on artificial water sources. This culture expanded significantly, likely assimilating the Halaf culture and spreading its influence peacefully across northern Mesopotamia, southeastern Anatolia, and northeastern Syria.

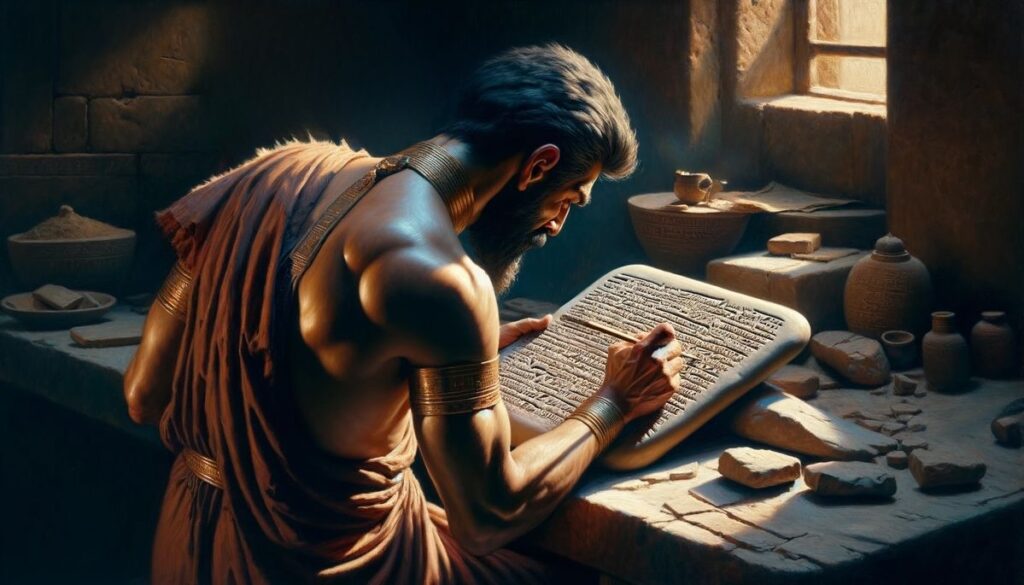

This period marked a transition from relatively non-hierarchical village societies to more complex urban centers. By the end of the 4th millennium BCE, these evolving social structures led to the emergence of a dominant elite class. Uruk and Tepe Gawra became two of the most influential centers in Mesopotamia, playing key roles in these societal changes. They were instrumental in the gradual development of writing and the concept of the state. This shift from prehistoric cultures to the edge of recorded history represents a significant epoch in human civilization, laying the groundwork for the historical periods that followed.

5500 BCE – 539

BCEANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

5500 BCE JAN 1 – 1800 BCE JAN

SUMER

Eridu, Sumeria, Iraq

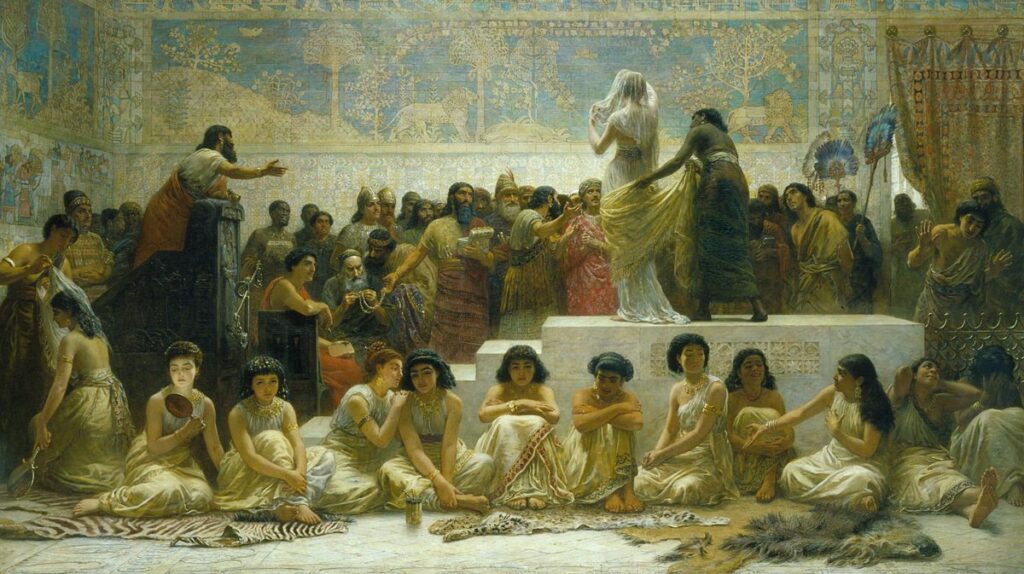

The settlement of Sumer, which began around 5500-3300 BCE, was founded by West Asian peoples who spoke Sumerian, a unique language that is neither Semitic nor Indo-European. This linguistic distinction is evident in the names of cities and rivers. The Sumerian civilization developed during the Uruk period in the 4th millennium BCE and continued to evolve through the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic periods. Eridu, a prominent Sumerian city, emerged as a cultural melting pot, integrating Ubaidian farmers, nomadic Semitic pastoralists, and marshland fisherfolk, who may have been among the ancestors of the Sumerians.

The preceding Ubaid period is notable for its distinctive pottery, which spread throughout Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. Ubaid culture, possibly influenced by the Samarran culture of northern Mesopotamia, is characterized by large settlements, mud-brick houses, and the construction of early public architecture in the form of temples. This period marked the onset of urbanization, with advancements in agriculture, animal domestication, and the introduction of ploughs from the north.

The transition to the Uruk period saw a shift toward mass-produced unpainted pottery. This era was characterized by significant urban growth, the use of slave labor, and extensive trade, which influenced surrounding regions. Sumerian cities were likely theocratic, governed by priest-kings and councils that included women. The Uruk period experienced limited organized warfare, with most cities remaining unwalled. The end of this period, around 3200-2900 BCE, coincided with the Piora oscillation, a climatic shift that marked the conclusion of the Holocene climatic optimum.

The subsequent dynastic period, generally dated to c. 2900 – c. 2350 BCE, witnessed a transition from temple-centered leadership to more secular governance and the emergence of historical figures like Gilgamesh. This era was marked by the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The Early Dynastic period featured multiple city-states—small states with relatively simple structures that evolved and solidified over time, ultimately leading to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite political fragmentation, the city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Notable Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur in Lower Mesopotamia were powerful and influential, while to the north and west, states centered around cities like Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla also emerged.

Eannatum of Lagash briefly established one of history’s first empires, encompassing much of Sumer and extending his influence beyond its borders. The Early Dynastic period was marked by the presence of multiple city-states, such as Uruk and Ur, which eventually unified under Sargon of the Akkadian Empire. Despite the political fragmentation, these city-states maintained a shared material culture.

2600 BCE JAN 1 – 2025 BCE

EARLY ASSYRIAN PERIOD

Ashur, Al-Shirqat،, Iraq

The Early Assyrian period (before 2025 BCE) marks the beginning of Assyrian history, preceding the Old Assyrian period. This era focuses on the history, people, and culture of Assur before it became an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I around 2025 BCE. Evidence from this period is scarce; however, archaeological findings at Assur date back to approximately 2600 BCE, during the Early Dynastic Period, suggesting that the city’s foundation may be older since the region has long been inhabited and nearby cities like Nineveh are significantly older.

Initially, the Hurrians likely inhabited Assur, which served as a center for a fertility cult dedicated to the goddess Ishtar. The name “Assur” is first recorded during the Akkadian Empire era in the 24th century BCE, although the city may have previously been known as Baltil. Before the rise of the Akkadian Empire, Semitic-speaking ancestors of the Assyrians settled in Assur, possibly displacing or assimilating the original inhabitants. Over time, Assur gradually became a deified city, ultimately personified as the god Ashur, the national deity of the Assyrians during Puzur-Ashur I’s reign.

During the Early Assyrian period, Assur was not an independent city but was controlled by various states and empires from southern Mesopotamia. It was significantly influenced by Sumerian culture during the Early Dynastic Period and even fell under the hegemony of Kish. Between the 24th and 22nd centuries BCE, Assur became part of the Akkadian Empire, serving as a northern administrative outpost. This period would later be regarded by Assyrian kings as a golden age. Before gaining independence, Assur existed as a peripheral city within the Third Dynasty of Ur’s Sumerian empire (c. 2112–2004 BCE).

2500 BCE JAN 1 – 1600 BCE

AMORITES

Mesopotamia, Iraq

The Amorites, a significant ancient people, are referenced in two Sumerian literary works from the Old Babylonian period: “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta” and “Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird.” These texts mention “the land of the mar.tu” and are linked to the Early Dynastic ruler of Uruk, Enmerkar, though the extent to which these references correspond to historical facts remains unclear.

As the Third Dynasty of Ur declined, the Amorites rose to prominence, prompting kings like Shu-Sin to construct extensive defensive walls. Contemporary records depict the Amorites as nomadic tribes led by chiefs, who encroached on grazing lands necessary for their herds. Akkadian literature from this era often portrays the Amorites unfavorably, emphasizing their nomadic and primitive lifestyle, as illustrated in the Sumerian myth “Marriage of Martu.”

The Amorites founded several notable city-states, including Isin, Larsa, Mari, and Ebla, and later established Babylon, which led to the emergence of the Old Babylonian Empire in the south. In the east, the Amorite kingdom of Mari rose to prominence before being conquered by Hammurabi. Key figures from this period include Shamshi-Adad I, who conquered Assur and established the Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia, and Hammurabi of Babylon. The Amorites also played a role in the rise of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt under the Hyksos around 1650 BCE.

By the 16th century BCE, the Amorite era in Mesopotamia waned with the decline of Babylon and the rise of the Kassites and Mitanni. From the 15th century BCE onward, the term “Amurru” came to denote a region stretching from northern Canaan to northern Syria. Eventually, the Syrian Amorites fell under the control of the Hittites and Middle Assyrians, and by around 1200 BCE, they were absorbed or displaced by other West Semitic-speaking peoples, particularly the Arameans. Although they vanished from historical records, their name continued to be referenced in the Hebrew Bible.

2334 BCE JAN 1 – 2154 BCE

AKKADIAN EMPIRE

Mesopotamia, Iraq

The Akkadian Empire, founded by Sargon of Akkad around 2334-2279 BCE, marks a pivotal era in ancient Mesopotamian history. As the first empire in the world, it established key precedents in governance, culture, and military strategy. This essay examines the origins, expansion, achievements, and eventual decline of the Akkadian Empire, emphasizing its enduring influence on history.

Originating in Mesopotamia, primarily in present-day Iraq, the Akkadian Empire rose under Sargon, who began as a cupbearer to King Ur-Zababa of Kish. Through military might and strategic alliances, Sargon overthrew the Sumerian city-states, successfully unifying northern and southern Mesopotamia under a single rule.

During the reigns of Sargon and his successors, including Naram-Sin and Shar-Kali-Sharri, the empire saw significant territorial expansion, reaching from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea and encompassing parts of modern-day Iran, Syria, and Turkey. The Akkadians implemented innovative administrative practices, organizing the empire into regions governed by loyal officials, a system that influenced future empires.

Culturally, the Akkadian Empire was a rich amalgamation of Sumerian and Semitic traditions, which enhanced its art, literature, and religious practices. The Akkadian language emerged as the empire’s lingua franca, serving as the medium for official documents and diplomatic communications. This era also witnessed notable advancements in technology and architecture, particularly the construction of ziggurats.

The Akkadian military, recognized for its discipline and organization, was instrumental in the empire’s expansion. With the introduction of composite bows and improved weaponry, they gained a significant advantage over their enemies. Military campaigns, celebrated in royal inscriptions and reliefs, highlighted the empire’s strength and strategic prowess.

The decline of the Akkadian Empire began around 2154 BCE, driven by internal rebellions, economic challenges, and invasions by the Gutians, a nomadic group. The erosion of central authority led to fragmentation, allowing new powers, such as the Third Dynasty of Ur, to rise in prominence.

2212 BCE JAN 1 – 2004 BCE

NEO-SUMERIAN EMPIRE

Ur, Iraq

The Third Dynasty of Ur, which succeeded the Akkadian Dynasty, marks a significant chapter in Mesopotamian history. Following the fall of the Akkadian Dynasty, the region entered a period of obscurity characterized by a lack of documentation and artifacts—except for records pertaining to Dudu of Akkad. During this time, the Gutian invaders rose to power, ruling for a period estimated to range from 25 to 124 years, depending on the source. Their reign resulted in a decline in agriculture and record-keeping, leading to famine and rising grain prices.

Utu-hengal of Uruk eventually overthrew the Gutians and was succeeded by Ur-Nammu, the founder of the Ur III Dynasty, who likely served as Utu-hengal’s governor. Ur-Nammu gained prominence after defeating the ruler of Lagash and is renowned for establishing the Code of Ur-Nammu, one of the earliest legal codes in Mesopotamia.

Under King Shulgi, significant progress was made, including the centralization of administration, standardization of processes, and territorial expansion. His military campaigns captured Susa and subdued the Elamite king Kutik-Inshushinak. The Ur III Dynasty expanded considerably, stretching from southeastern Anatolia to the Persian Gulf, with the spoils of war primarily benefiting the kings and temples of Ur.

The dynasty frequently engaged in conflicts with highland tribes from the Zagros Mountains, such as the Simurrum and Lullubi, as well as with Elam. During this period, Semitic military leaders known as Shakkanakkus, such as Puzur-Ishtar in the Mari region, coexisted with or slightly preceded the Ur III Dynasty.

The decline of the dynasty began under Ibbi-Sin, who faced challenges in military campaigns against Elam. In 2004/1940 BCE, the Elamites, allied with Susa and led by Kindattu of the Shimashki dynasty, captured Ur and Ibbi-Sin, effectively marking the end of the Ur III Dynasty. The Elamites subsequently occupied the region for 21 years.

Following the Ur III period, the area came under the influence of the Amorites, leading to the Isin-Larsa period. The Amorites, originally nomadic tribes from the northern Levant, gradually adopted agriculture and established independent dynasties in various Mesopotamian cities, including Isin, Larsa, and eventually Babylon.

2025 BCE JAN 1 – 1763 BCE

ISIN-LARSA PERIOD OF MESAPOTAMIA

Larsa, Iraq

The Isin-Larsa period, spanning from around 2025 to 1763 BCE, was a vibrant era in Mesopotamian history following the decline of the Third Dynasty of Ur. During this time, the city-states of Isin and Larsa dominated southern Mesopotamia.

Isin rose to prominence under Ishbi-Erra, who established its dynasty around 2025 BCE by freeing Isin from the weakening Ur III dynasty. The city became notable for restoring cultural and religious traditions, particularly the worship of the moon god Nanna/Sin, a key figure in Sumerian religion.

Leaders like Lipit-Ishtar (1934-1924 BCE) played a crucial role in the development of legal and administrative practices. Lipit-Ishtar is known for creating an early law code, predating the famous Code of Hammurabi, which helped maintain social order and justice.

Simultaneously, Larsa gained prominence under the Amorite dynasty, especially during the reign of King Naplanum, who established its independence. King Gungunum (c. 1932-1906 BCE) furthered Larsa’s influence through territorial expansion and economic prosperity by controlling trade routes and agricultural resources.

The rivalry between Isin and Larsa shaped the period, with frequent conflicts and shifting alliances involving other city-states and powers like Elam. Eventually, the balance shifted in favor of Larsa under King Rim-Sin I (c. 1822-1763 BCE), whose military campaigns subdued many neighboring states, including Isin, ending its dynasty.

Culturally, this era saw significant advancements in art, literature, and architecture, with a revival of Sumerian language and literature and progress in astronomy and mathematics. Temples and ziggurats from this time showcase the architectural skill of the period.

The Isin-Larsa period concluded with the rise of Babylon under King Hammurabi, who conquered Larsa in 1763 BCE, unifying southern Mesopotamia and ushering in the Old Babylonian period. This marked not only a political shift but also a cultural transition, paving the way for the evolution of Mesopotamian civilization under Babylonian rule.

2025 BCE JAN 1 – 1363 BCE

OLD ASSYRIAN PERIOD OF MESOPOTAMIA

Ashur, Al Shirqat, Iraq

The Old Assyrian period (2025 – 1363 BCE) was pivotal in the development of Assyrian culture, which was distinct from that of southern Mesopotamia. This era began with the rise of Assur as an independent city-state under the leadership of Puzur-Ashur I and transitioned into the Middle Assyrian period with Ashur-uballit I, who established a larger territorial state.

For much of this time, Assur functioned as a minor city-state with limited political and military influence. Its leaders, known as Išši’ak Aššur (“governor of Ashur”), were integral to the city’s administration, called the Ālum. Despite its modest power, Assur emerged as an economic hub, particularly notable from the reign of Erishum I (c. 1974-1935 BCE) for its extensive trading network, which extended from the Zagros Mountains to central Anatolia.

The first Assyrian dynasty, established by Puzur-Ashur I, came to an end when the Amorite conqueror Shamshi-Adad I captured Assur around 1808 BCE, founding the short-lived Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia. Following Shamshi-Adad’s death in 1776 BCE, Assur experienced decades of conflict with the Old Babylonian Empire, Mari, Eshnunna, and various Assyrian factions. Around 1700 BCE, the city reemerged as an independent entity under the Adaside dynasty. Assur became a vassal of the Mitanni kingdom around 1430 BCE but later regained independence and expanded under warrior-kings.

The Old Assyrian trading colony at Kültepe yielded over 22,000 clay tablets, providing valuable insights into the culture, language, and society of the period. The Assyrians practiced slavery, though some individuals labeled as ‘slaves’ may have been free servants due to the ambiguous terminology used in the texts. Men and women enjoyed similar legal rights, including the ability to inherit property and engage in trade. The chief deity of the Assyrians was Ashur, who symbolized the city itself.

2004 BCE JAN 1

FALL OF UR

Ur, Iraq

The fall of Ur to the Elamites around 2004 BCE (middle chronology) or 1940 BCE (short chronology) marked a pivotal moment in Mesopotamian history, signaling the end of the Ur III dynasty and dramatically altering the region’s political landscape.

Under King Ibbi-Sin, the Ur III dynasty faced a multitude of challenges that ultimately led to its collapse. Once a formidable empire, it was weakened by internal discord, economic hardships, and external threats. A severe famine compounded Ur’s vulnerabilities, exacerbating administrative and economic difficulties.

Seizing the opportunity, the Elamites, led by King Kindattu of the Shimashki dynasty, launched a successful military campaign against Ur. The city’s fall was dramatic, culminating in a siege that resulted in its sacking and the capture of Ibbi-Sin, who was taken prisoner to Elam.

This conquest represented not just a military triumph but also a significant power shift from the Sumerians to the Elamites, who established control over large portions of southern Mesopotamia and left a lasting impact on the region’s culture and politics.

In the aftermath of Ur’s downfall, the region fragmented into smaller city-states and kingdoms, such as Isin, Larsa, and Eshnunna, each vying for dominance in the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Ur III dynasty. This era, known as the Isin-Larsa period, was characterized by political instability and frequent conflicts.

The fall of Ur also had profound cultural implications, marking the end of the Sumerian city-state governance model and paving the way for the rise of Amorite influence. The Amorites, a Semitic people, began establishing their own dynasties in various Mesopotamian city-states, reshaping the region’s political and cultural identity.

1894 BCE JAN 1 – 1595 BCE

OLD BABYLONIAN EMPIRE

Babylon, Iraq

The Old Babylonian Empire, flourishing from around 1894 to 1595 BCE, marks a significant transformative period in Mesopotamian history. This era is particularly notable for the rise of Hammurabi, one of history’s most famous rulers, who ascended to the throne in 1792 BCE (or 1728 BCE in short chronology). His reign, which lasted until 1750 BCE (or 1686 BCE), was characterized by substantial territorial expansion and cultural development in Babylon.

One of Hammurabi’s major accomplishments was liberating Babylon from Elamite control, a critical step in establishing the city’s independence and paving the way for its emergence as a regional power. Under his leadership, Babylon underwent extensive urban development, transforming from a small town into a major city.

Hammurabi’s military campaigns were instrumental in shaping the Old Babylonian Empire. He expanded Babylon’s territory across southern Mesopotamia, incorporating key cities such as Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, Kish, Lagash, Nippur, Borsippa, Ur, Uruk, Umma, Adab, Sippar, Rapiqum, and Eridu. These conquests brought stability to a previously fragmented region.

In addition to his military achievements, Hammurabi is best known for the Code of Hammurabi, a groundbreaking legal compilation that has had a lasting influence on future legal systems. Discovered in 1901 at Susa and now housed in the Louvre, this code is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length, showcasing advanced legal thought and an emphasis on justice.

Culturally and religiously, the Old Babylonian Empire thrived under Hammurabi’s rule. He elevated the god Marduk to the highest position in the southern Mesopotamian pantheon, further establishing Babylon as a cultural and spiritual hub.

However, the empire’s prosperity waned after Hammurabi’s death. His successor, Samsu-iluna (1749–1712 BCE), faced significant challenges, including the loss of southern Mesopotamia to the Sealand Dynasty. Subsequent rulers struggled to maintain the integrity of the empire.

The decline of the Old Babylonian Empire culminated with the Hittite sack of Babylon in 1595 BCE, led by King Mursili I. This event marked the end of the Amorite dynasty and significantly altered the geopolitical landscape of the ancient Near East. After the Hittites withdrew, the Kassite dynasty rose to power, signaling the conclusion of the Old Babylonian period and the beginning of a new chapter in Mesopotamian history.

1595 BCE JAN 1

SACK OF BABYLON

Babylon, Iraq

Before 1595 BCE, Southern Mesopotamia experienced significant decline and political instability during the Old Babylonian period. This downturn was largely attributed to Hammurabi’s successors’ inability to maintain control over the kingdom. A critical factor in this decline was the loss of control over essential trade routes between northern and southern Babylonia to the First Sealand Dynasty, which had severe economic consequences.

Around 1595 BCE, Hittite King Mursili I invaded Southern Mesopotamia after defeating Aleppo, a powerful neighboring kingdom. The Hittites subsequently sacked Babylon, effectively ending the Hammurabi dynasty and the Old Babylonian period, marking a pivotal moment in Mesopotamian history.

Despite their conquest, the Hittites did not establish a lasting rule over Babylon. Instead, they withdrew along the Euphrates River back to their homeland, known as “Hatti-land.” The motivations behind the Hittite invasion remain a topic of debate among historians. Some suggest that Hammurabi’s successors may have been allied with Aleppo, prompting Hittite intervention. Alternatively, the Hittites might have aimed to secure land, manpower, trade routes, and access to valuable resources, reflecting broader strategic objectives.

1595 BCE JAN 1 – 1155 BCE

MIDDLE BABYLONIAN PERIOD

Babylon, Iraq

The Middle Babylonian period, also known as the Kassite period, lasted from approximately 1595 to 1155 BCE in southern Mesopotamia, following the Hittite sack of Babylon. Established by Gandash of Mari, the Kassite Dynasty marked a significant era, enduring for 576 years—the longest dynasty in Babylonian history. During this time, the Kassites renamed Babylon Karduniaš. Originating from the Zagros Mountains in northwestern Iran, the Kassites were not native to Mesopotamia. Their language, possibly related to the Hurro-Urartian family, remains largely obscure due to limited textual evidence. While some Kassite leaders bore Indo-European names, suggesting an Indo-European elite, others had Semitic names. Under Kassite rule, the divine titles previously used by Amorite kings were abandoned, and the title “god” was never ascribed to a Kassite sovereign. Despite these changes, Babylon continued to be a major religious and cultural center.

During this period, Babylonia experienced fluctuations in power, often influenced by Assyria and Elam. Early Kassite rulers, such as Agum II, who came to power in 1595 BCE, maintained peaceful relations with regions like Assyria and resisted the Hittite Empire.

The Kassite rulers engaged in various diplomatic and military endeavors. Burnaburiash I established peace with Assyria, while Ulamburiash conquered parts of the Sealand Dynasty around 1450 BCE. Significant architectural projects were initiated, including a temple in Uruk by Karaindash and the establishment of a new capital, Dur-Kurigalzu, by Kurigalzu I.

The dynasty faced challenges from external powers like Elam. Kings such as Kadašman-Ḫarbe I and Kurigalzu I contended with Elamite invasions and internal threats from groups like the Suteans.

In the latter part of the Kassite Dynasty, conflicts with Assyria and Elam persisted. Rulers like Burna-Buriash II maintained diplomatic ties with Egypt and the Hittite Empire. However, the rise of the Middle Assyrian Empire posed new challenges, ultimately leading to the dynasty’s decline.

The Kassite period came to an end with Babylonia’s conquest by Elam under Shutruk-Nakhunte and later by Nebuchadnezzar I, coinciding with the broader Late Bronze Age collapse. Despite the military and cultural challenges it faced, the Kassite Dynasty’s long reign exemplifies its resilience and adaptability within the shifting landscape of ancient Mesopotamia.

1365 BCE JAN 1 – 912 BCE

MIDDLE ASSYRIAN EMPIRE

Ashur, Al Shirqat, Iraq

The Middle Assyrian Empire, which spanned from the ascension of Ashur-uballit I around 1365 BCE to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BCE, represents a significant period in Assyrian history. During this era, Assyria transformed from a city-state with trading colonies in Anatolia and influence in southern Mesopotamia—dating back to the 21st century BCE—into a major empire.

Under Ashur-uballit I, Assyria gained independence from the Mitanni kingdom and embarked on a path of expansion. Key rulers such as Adad-nirari I (circa 1305–1274 BCE), Shalmaneser I (circa 1273–1244 BCE), and Tukulti-Ninurta I (circa 1243–1207 BCE) played vital roles in establishing Assyrian dominance over Mesopotamia and the Near East, surpassing rival powers like the Hittites, Egyptians, Hurrians, Mitanni, Elamites, and Babylonians.

The reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I marked the zenith of the Middle Assyrian Empire, characterized by the subjugation of Babylonia and the establishment of the new capital, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta. However, his assassination around 1207 BCE sparked inter-dynastic conflicts and a decline in Assyrian power, although the empire managed to remain relatively resilient during the broader Late Bronze Age collapse.

Even amid this decline, rulers such as Ashur-dan I (circa 1178–1133 BCE) and Ashur-resh-ishi I (circa 1132–1115 BCE) continued military campaigns, particularly against Babylonia. A resurgence in Assyrian influence occurred under Tiglath-Pileser I (circa 1114–1076 BCE), who extended Assyrian power into the Mediterranean, the Caucasus, and the Arabian Peninsula. Following Tiglath-Pileser, however, the empire faced a more severe decline due to invasions by the Arameans.

The reign of Ashur-dan II (circa 934–912 BCE) marked a pivotal turning point, laying the groundwork for the Neo-Assyrian Empire through further territorial expansion.

Theologically, this period was crucial for the evolution of the deity Ashur. Initially a personification of the city of Assur, Ashur became associated with the Sumerian god Enlil and evolved into a military deity, reflecting the empire’s expansion and focus on warfare.

Politically and administratively, the Middle Assyrian Empire underwent significant transformations. The shift from a city-state to an expansive empire necessitated the development of sophisticated systems for administration, communication, and governance. Assyrian kings, once known as iššiak (“governor”) and ruling alongside a city assembly, evolved into autocratic rulers with the title šar (“king”), reflecting their elevated status similar to that of monarchs in other empires.

1200 BCE JAN 1 – 1150 BCE

LATE BRONZE AGE COLLAPSE

Babylon, Iraq

The Late Bronze Age collapse, occurring in the 12th century BCE, marked a period of profound upheaval across the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East, impacting regions such as Egypt, the Balkans, Anatolia, and the Aegean. This era was characterized by environmental changes, mass migrations, widespread destruction of cities, and the disintegration of major civilizations, resulting in a transition from the palace economies of the Bronze Age to smaller, isolated village cultures typical of the subsequent Greek Dark Ages.

Several prominent Bronze Age states fell during this collapse, including the disintegration of the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and parts of the Levant, as well as the decline of the Mycenaean civilization in Greece, which entered a period known as the Greek Dark Ages, lasting from around 1100 to 750 BCE. While some states, such as the Middle Assyrian Empire and the New Kingdom of Egypt, survived, they emerged significantly weakened. In contrast, cultures like the Phoenicians gained autonomy and influence due to the diminished military presence of dominant powers like Egypt and Assyria.

The causes of the Late Bronze Age collapse remain the subject of extensive debate among historians. Proposed theories include natural disasters, climatic changes, technological advancements, and societal shifts. Commonly cited factors include volcanic eruptions, severe droughts, diseases, and invasions by the enigmatic Sea Peoples. Economic disruptions, particularly the rise of ironworking and changes in military technology that rendered chariot warfare obsolete, also contributed to the decline. While earthquakes were once thought to play a significant role, recent research suggests their impact may have been overstated.

In the aftermath of the collapse, the region underwent transformative changes, notably the transition from Bronze Age to Iron Age metallurgy. This technological shift facilitated the emergence of new civilizations and reshaped the socio-political landscape across Eurasia and Africa, laying the groundwork for developments in the 1st millennium BCE.

Between 1200 and 1150 BCE, significant cultural collapses occurred throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East. The Mycenaean kingdoms, the Kassites in Babylonia, the Hittite Empire, and the New Kingdom of Egypt all fell, alongside the destruction of Ugarit and the Amorite states, fragmentation of the Luwian states in western Anatolia, and chaos in Canaan. These disruptions affected trade routes and contributed to a decline in literacy across the region.

Some states managed to survive the Bronze Age collapse, albeit in weakened forms. These included Assyria, the New Kingdom of Egypt, the Phoenician city-states, and Elam. However, by the late 12th century BCE, Elam experienced a decline following defeats by Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon, who briefly revitalized Babylonian power before suffering losses to the Assyrians. After the death of Ashur-bel-kala in 1056 BCE, Assyria entered a century-long decline, with its control receding to core regions. The Phoenician city-states regained independence from Egypt during the era of Wenamun.

Historically, it was believed that a widespread disaster struck the Eastern Mediterranean from Pylos to Gaza in the 13th and 12th centuries BCE, resulting in the violent destruction and abandonment of major cities such as Hattusa, Mycenae, and Ugarit. Robert Drews famously stated that almost every significant city was destroyed during this period, many never to be reoccupied. However, recent research by Ann Killebrew suggests that Drews may have overestimated the extent of this destruction. Killebrew’s findings indicate that while cities like Jerusalem were significant and fortified in earlier and later periods, they were smaller, unfortified, and less prominent during the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Age.

Various theories have been proposed to explain the collapse, including climate change, invasions by the Sea Peoples, the spread of iron metallurgy, advancements in military technology, and failures in political, social, and economic systems. It is likely that the collapse resulted from a combination of these factors.

The designation of 1200 BCE as the beginning of the Late Bronze Age decline was influenced by historian Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren, who associated this date with the fall of Troy in 1190 BCE and the end of Egypt’s 19th Dynasty. By 1896, this timeframe also marked significant events, including the invasion of the Sea Peoples, the Dorian invasion, and the collapse of Mycenaean Greece, shaping the scholarly narrative surrounding the Late Bronze Age collapse.

In the aftermath, remnants of the Hittite civilization formed small Syro-Hittite states in Cilicia and the Levant, characterized by a blend of Hittite and Aramean elements. By the mid-10th century BCE, small Aramean kingdoms emerged in the Levant, while the Philistines settled in southern Canaan. Canaanite speakers also formed polities such as Israel, Moab, Edom, and Ammon, marking a significant transformation in the region’s political landscape.

1155 BCE JAN 1 – 1026 BCE

SECOND DYNASTY OF ISIN

Babylon, Iraq

After the Elamite occupation of Babylonia, the region underwent significant political changes. Around 1155 BCE, Marduk-kabit-ahheshu established Babylon’s Dynasty IV, the first native Akkadian-speaking dynasty in South Mesopotamia. He expelled the Elamites and thwarted a potential Kassite revival. During his reign, he engaged in conflicts with Assyria, successfully capturing Ekallatum but ultimately facing defeat at the hands of Ashur-Dan I.

His successor, Itti-Marduk-balatu (1138 BCE), defended Babylonia against Elamite incursions during his eight-year reign but struggled to mount a successful offensive against Assyria. In 1127 BCE, Ninurta-nadin-shumi ascended to the throne and launched military campaigns against Assyria. However, his attempt to assault Arbela ended in defeat at the hands of Ashur-resh-ishi I, resulting in a treaty that favored Assyria.

The most notable ruler of this dynasty was Nebuchadnezzar I (1124–1103 BCE), who achieved significant victories against Elam, reclaiming territories and the sacred statue of Marduk. Despite his successes, he suffered defeats against Ashur-resh-ishi I while trying to expand into former Hittite territories. Following these military endeavors, he shifted his focus to constructing and fortifying Babylon’s defenses.

After Nebuchadnezzar I, Enlil-nadin-apli (1103–1100 BCE) and Marduk-nadin-ahhe (1098–1081 BCE) continued to confront Assyrian aggression. Marduk-nadin-ahhe initially enjoyed some successes, but his reign was marred by defeats against Tiglath-Pileser I, resulting in territorial losses and famine in Babylon.

Marduk-shapik-zeri (circa 1072 BCE) managed to negotiate a peace treaty with Assyria; however, his successor, Kadašman-Buriaš, faced renewed Assyrian hostility, which led to Assyrian domination until approximately 1050 BCE. Subsequent rulers, such as Marduk-ahhe-eriba and Marduk-zer-X, were effectively vassals of the Assyrians.

The decline of the Middle Assyrian Empire around 1050 BCE, caused by internal strife and external conflicts, provided Babylonia with a temporary respite from Assyrian control. However, this period also saw incursions by West Semitic nomadic groups, particularly the Arameans and Suteans, who settled in large areas of Babylonia, further exposing the region’s vulnerabilities.

1026 BCE JAN 1 – 911 BCE

PERIOD OF CHAOS IN BABYLON

Babylon, Iraq

Around 1026 BCE, Babylonia was engulfed in significant turmoil and political fragmentation. The Nabu-shum-libur dynasty was overthrown due to Aramean invasions, resulting in over two decades of anarchy that left Babylon without a ruler.

In southern Mesopotamia, particularly in the region previously ruled by the old Sealand Dynasty, a new independent state emerged under Dynasty V (1025–1004 BCE), led by Simbar-shipak from a Kassite clan. The chaos in Babylon created an opportunity for Assyrian intervention, with Ashur-nirari IV (1019–1013 BCE) invading in 1018 BCE and capturing the city of Atlila along with parts of south-central Mesopotamia.

Following Dynasty V, another Kassite dynasty (Dynasty VI; 1003–984 BCE) briefly restored control over Babylon. However, this resurgence was short-lived, as the Elamites, under the leadership of Mar-biti-apla-usur, swiftly overthrew the Kassite rulers to establish Dynasty VII (984–977 BCE), which also succumbed to further Aramean invasions.

In 977 BCE, Nabû-mukin-apli reestablished Babylonian sovereignty and founded Dynasty VIII. This was followed by Dynasty IX, which began with Ninurta-kudurri-usur II in 941 BCE. Throughout this period, Babylonia remained weak, with significant portions of the region under the control of Aramean and Sutean populations. Babylonian rulers often found themselves influenced by, or in conflict with, more powerful regional powers such as Assyria and Elam, both of which annexed parts of Babylonian territory.

911 BCE JAN 1 – 605 BCE

NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE

Nineveh Governorate, Iraq

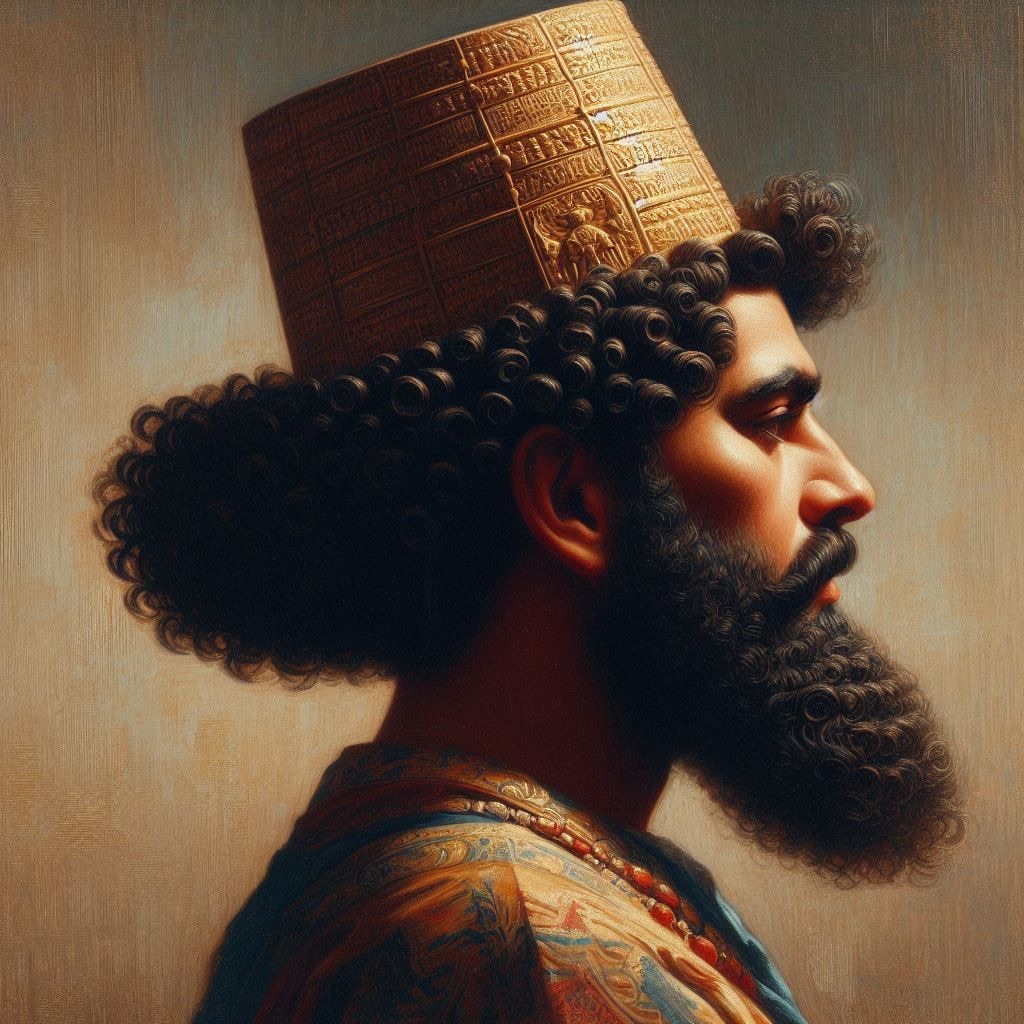

The Neo-Assyrian Empire, spanning from Adad-nirari II’s accession in 911 BCE to the late 7th century BCE, marks a crucial chapter in ancient Assyrian history. Often regarded as the first true world empire, it exerted unprecedented geopolitical dominance and pursued an ideology of world domination. This empire significantly influenced various ancient cultures, including the Babylonians, Achaemenids, and Seleucids, and emerged as the strongest military power of its era, extending its reach across Mesopotamia, the Levant, Egypt, parts of Anatolia, Arabia, Iran, and Armenia.

Early Neo-Assyrian kings focused on reclaiming control over northern Mesopotamia and Syria. Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE) reestablished Assyria as the dominant Near Eastern power through military campaigns that reached the Mediterranean, relocating the capital from Assur to Nimrud. His successor, Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE), further expanded the empire, although it experienced stagnation after his death, entering a period known as the “age of the magnates.”

The empire regained momentum under Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BCE), who significantly expanded its territory, incorporating Babylonia and parts of the Levant. During the Sargonid dynasty (722 BCE until the empire’s fall), Assyria reached its zenith, with notable achievements including Sennacherib’s (705–681 BCE) establishment of Nineveh as the capital and Esarhaddon’s (681–669 BCE) conquest of Egypt. Despite its peak, the empire fell rapidly in the late 7th century BCE due to a Babylonian uprising and a Median invasion, with the reasons for this collapse remaining a topic of debate among historians.

The success of the Neo-Assyrian Empire can be attributed to its expansionist policies and administrative efficiency. Military innovations, such as the extensive use of cavalry and advanced siege techniques, influenced warfare for generations. The empire also established a sophisticated communication network with relay stations and well-maintained roads, unmatched in speed across the Middle East until the 19th century. Additionally, its resettlement policies integrated conquered territories and promoted Assyrian agricultural techniques, leading to a dilution of cultural diversity and the emergence of Aramaic as the lingua franca.

The legacy of the Neo-Assyrian Empire profoundly impacted later empires and cultural traditions. Its political structures served as models for future rulers, and its concept of universal rule inspired subsequent empires. The empire’s influence was significant in shaping early Jewish theology, impacting Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Moreover, its folklore and literary traditions continued to resonate in northern Mesopotamia long after its decline. Contrary to perceptions of excessive brutality, the actions of the Assyrian military were not uniquely harsh compared to those of other civilizations in history.

626 BCE JAN 1 – 539 BCE

NEO-BABYLONIAN EMPIRE

Babylon, Iraq

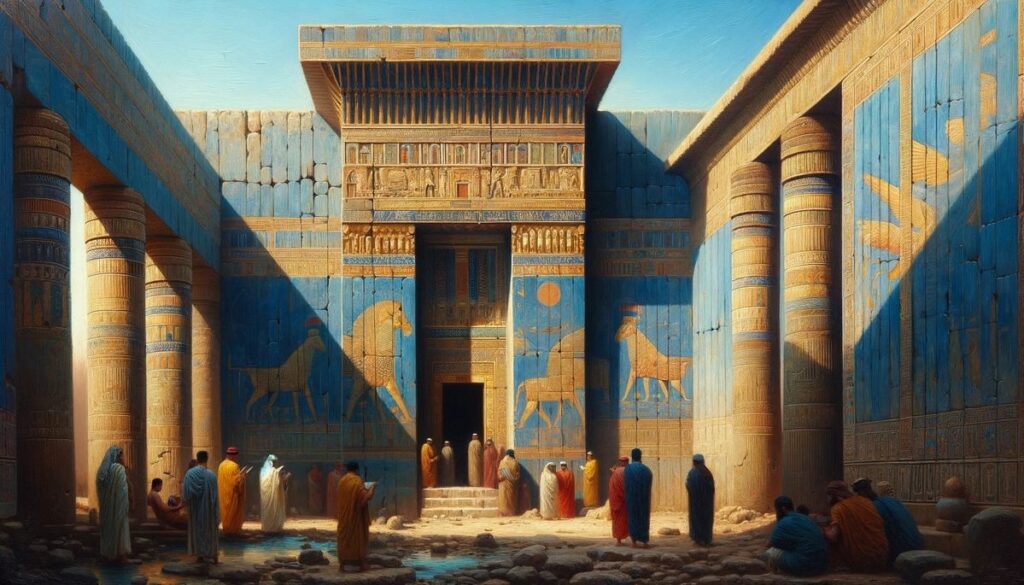

The Neo-Babylonian Empire, also known as the Second Babylonian or Chaldean Empire, was the final Mesopotamian empire ruled by native monarchs. It began with the coronation of Nabopolassar in 626 BCE and solidified its power following the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE. However, the empire fell to the Achaemenid Persian Empire in 539 BCE, ending the Chaldean dynasty in under a century.

This empire marked the resurgence of Babylon and southern Mesopotamia as significant forces in the Near East, the first time since the Old Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi nearly a thousand years earlier. The Neo-Babylonian period was characterized by economic and population growth, as well as a cultural renaissance. The kings of this era initiated extensive building projects that revived elements from over 2,000 years of Sumero-Akkadian culture, particularly in Babylon.

The empire is notably remembered for its biblical portrayal, especially concerning Nebuchadnezzar II’s military actions against Judah and the siege of Jerusalem in 587 BCE, which resulted in the destruction of Solomon’s Temple and the subsequent Babylonian captivity. Babylonian records, however, depict Nebuchadnezzar’s reign as a golden age, elevating Babylon to unprecedented heights.

The empire’s decline can be partly attributed to the religious policies of its last king, Nabonidus, who favored the moon god Sîn over Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon. This shift provided Cyrus the Great of Persia with a pretext for invasion in 539 BCE, allowing him to present himself as the restorer of Marduk’s worship. Despite this conquest, Babylon retained its cultural identity for centuries, with references to Babylonian names and religion persisting up to the 1st century BCE during the Parthian Empire. Despite several uprisings, Babylon never regained its independence.

539 BCE – 632

CLASSICAL MESOPOTAMIA

539 BCE JAN 1 – 330 BCE

ACHAEMENID ASSYRIA

Iraq

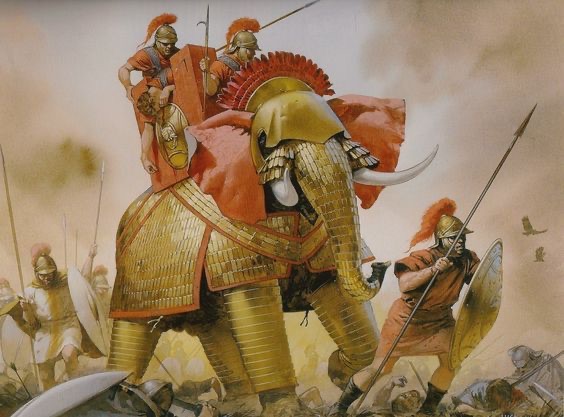

Mesopotamia was conquered by the Achaemenid Persians under Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE and remained under Persian rule for two centuries. During this period, both Assyria and Babylonia thrived, with Achaemenid Assyria serving as a crucial source of manpower for the military and a vital agricultural region for the economy. Mesopotamian Aramaic continued to be the lingua franca of the Achaemenid Empire, much like it had been during Assyrian times. Unlike the Neo-Assyrians, the Achaemenid Persians largely refrained from interfering in the internal affairs of their territories, focusing instead on ensuring a consistent flow of tribute and taxes.

Athura, known as Assyria within the Achaemenid Empire, was a region in Upper Mesopotamia from 539 to 330 BCE. It functioned as a military protectorate rather than a traditional satrapy. Achaemenid inscriptions refer to Athura as a “dahyu,” meaning a group of people or a country, without suggesting any specific administrative structure. Athura encompassed most of the former Neo-Assyrian Empire territories, which now include parts of northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, northeastern Syria, and southeastern Anatolia, while excluding Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula. Assyrian soldiers played a significant role in the Achaemenid military as heavy infantry. Despite initial devastation, Athura proved to be a prosperous region, especially in agriculture, countering earlier perceptions of it as a wasteland.

312 BCE JAN 1 – 63 BCE

SELEUCID MESOPOTAMIA

Mesopotamia, Iraq

In 331 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, incorporating it into the Hellenistic world under the Seleucid Empire. With the establishment of Seleucia on the Tigris as the new capital, Babylon’s significance diminished. At its zenith, the Seleucid Empire extended from the Aegean Sea to India, emerging as a major center of Hellenistic culture. This period was characterized by the prevalence of Greek customs and a political elite of Greek origin, particularly in urban areas, supported by waves of immigrants from Greece. By the mid-2nd century BCE, the Parthians, under the leadership of Mithridates I, had seized much of the empire’s eastern territories.

141 BCE JAN 1 – 224

PARTHIAN & ROMAN RULE IN MESOPOTAMIA

Mesopotamia, Iraq

The Parthian Empire’s control over Mesopotamia began in the mid-2nd century BCE, following Mithridates I’s conquests, which marked a significant transition from Hellenistic to Parthian influence. Reigning from 171 to 138 BCE, Mithridates I expanded Parthian territory into Mesopotamia and captured Seleucia in 141 BCE. This pivotal event signified the decline of Seleucid power and the emergence of Parthian dominance, shifting the balance of influence in the Near East from the Greeks to the Parthians.

Under Parthian rule, Mesopotamia became a vital center for trade and cultural exchange. The Parthian Empire was known for its tolerance and diversity, allowing various religions and cultures to flourish. With its rich history and strategic location, Mesopotamia played a key role in this cultural melting pot.

A fusion of Greek and Persian cultural elements emerged in Mesopotamian art, architecture, and coinage, reflecting the Parthian Empire’s ability to integrate diverse influences while retaining its own identity.

In the early 2nd century CE, Roman Emperor Trajan invaded Parthia, temporarily conquering Mesopotamia and turning it into a Roman province. However, his successor, Hadrian, quickly restored Mesopotamia to Parthian control.

During this time, Christianity began to spread in Mesopotamia, having arrived in the region by the 1st century CE. Roman Syria became a significant hub for Eastern Rite Christianity and the Syriac literary tradition, signaling a major transformation in the area’s religious landscape.

Meanwhile, traditional Sumerian-Akkadian religious practices began to wane, marking the end of an era. The use of cuneiform also declined. Despite these cultural changes, the Assyrian national god Ashur continued to be revered in his home city, with temples dedicated to him surviving as late as the 4th century CE, demonstrating a lasting respect for ancient traditions amidst the rise of new belief systems.

224 JAN 1 – 651

SASSANID MESOPOTAMIA

Mesopotamia, Iraq

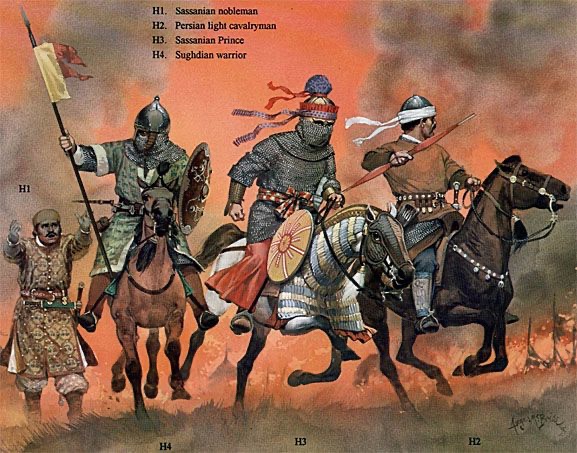

In the 3rd century CE, the Parthians were succeeded by the Sassanid dynasty, which ruled Mesopotamia until the Islamic invasion in the 7th century. During this period, the Sassanids conquered independent states such as Adiabene, Osroene, Hatra, and eventually Assur. By the mid-6th century, the Persian Empire under Khosrow I was divided into four quarters, with the western quarter, Khvārvarān, encompassing much of modern Iraq and subdivided into provinces like Mishān, Asoristān (Assyria), Adiabene, and Lower Media.

Asoristān, meaning “land of Assyria” in Middle Persian, became the capital province of the Sassanian Empire, referred to as Dil-ī Ērānshahr, or “Heart of Iran.” Ctesiphon served as the capital for both the Parthian and Sassanian Empires, once recognized as the largest city in the world. The primary language spoken by the Assyrian population was Eastern Aramaic, which still persists among the Assyrians today, while Syriac emerged as an important language for Syriac Christianity. Asoristān largely aligned with ancient Mesopotamia.

The Sassanid period saw a significant influx of Arabs into the region. Upper Mesopotamia came to be known as Al-Jazirah in Arabic, meaning “The Island,” situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, while Lower Mesopotamia was referred to as ʿIrāq-i ʿArab, meaning “the escarpment of the Arabs.” In medieval Arabic sources, the term “Iraq” was used geographically rather than politically.

Until 602 CE, the desert frontier of the Persian Empire was protected by the Arab Lakhmid kings of Al-Hirah. However, in that year, Shahanshah Khosrow II Aparviz abolished the Lakhmid kingdom, leaving the frontier vulnerable to nomadic incursions. To the north, the western quarter bordered the Byzantine Empire, with the frontier following the modern Syria-Iraq border and continuing northward between Nisibis (modern Nusaybin), which served as a Sassanian fortress, and Dara and Amida (modern Diyarbakır), held by the Byzantines.

632 – 1533

MEDIEVAL IRAQ

632 JAN 1 – 654

MUSLIM CONQUEST OF MESOPOTAMIA

Mesopotamia, Iraq

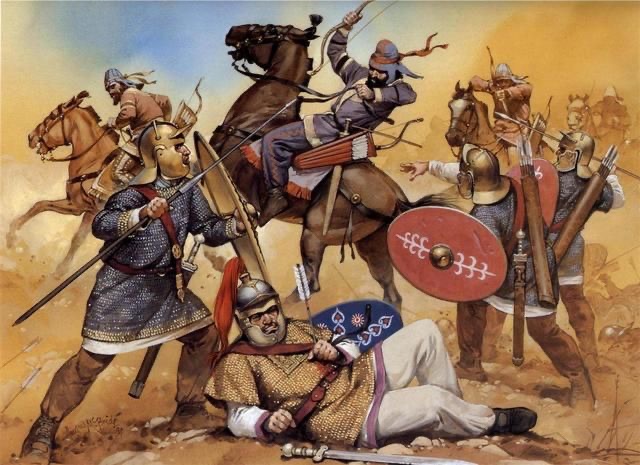

The first significant conflict between Arab invaders and Persian forces in Mesopotamia took place in 634 CE at the Battle of the Bridge, where a Muslim army of about 5,000, led by Abū ʿUbayd ath-Thaqafī, was defeated by the Persians. Despite this initial setback, Khalid ibn al-Walid soon launched a successful campaign that resulted in the Arab conquest of nearly all of Iraq within a year, with the exception of the Persian capital, Ctesiphon.

A critical turning point occurred in 636 CE when a larger Muslim force commanded by Saʿd ibn Abī Waqqās triumphed over the main Persian army at the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah. This decisive victory opened the way for the capture of Ctesiphon. By the end of 638 CE, the Muslims had conquered all of the Western Sassanid provinces, encompassing modern-day Iraq. The last Sassanid Emperor, Yazdegerd III, fled to central and later northern Persia, where he was ultimately killed in 651 CE.

The Islamic conquests represented one of the most significant Semitic expansions in history. The Arab conquerors established new garrison cities, notably al-Kūfah near ancient Babylon and Basrah in the south. However, northern Iraq retained its predominantly Assyrian and Arab Christian character.

762 JAN 1

ABBASID CALIPHATE & FOUNDING OF BAGHDAD

Baghdad, Iraq

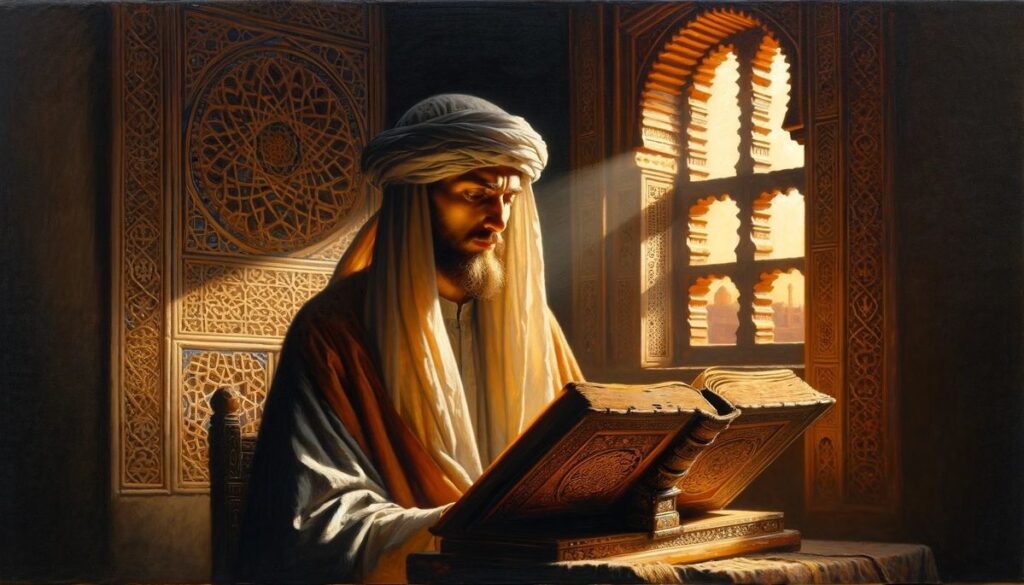

Founded in the 8th century, Baghdad quickly emerged as the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate and became a cultural hub for the Muslim world. It served as the epicenter of the Islamic Golden Age for five centuries. Following the Muslim conquest, Asōristān saw a significant influx of Muslim populations, beginning with Arabs in the south and later including Iranian (Kurdish) and Turkic peoples during the Middle Ages.

The Islamic Golden Age, marked by remarkable advancements in science, economics, and culture, is traditionally dated from the 8th to the 13th century. It is often regarded as having begun during the reign of Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809) and with the establishment of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. This institution became a renowned center of learning, drawing scholars from across the Muslim world to translate classical texts into Arabic and Persian. At this time, Baghdad was the largest city in the world, thriving as a hub of intellectual and cultural activity.

However, by the 9th century, the Abbasid Caliphate began to decline. During the “Iranian Intermezzo,” from the late 9th to early 11th centuries, various minor Iranian emirates, including the Tahirids, Saffarids, Samanids, Buyids, and Sallarids, governed parts of present-day Iraq. In 1055, Tughril of the Seljuk Empire captured Baghdad, though the Abbasid caliphs retained a ceremonial position. Despite losing political power, the Abbasid court in Baghdad continued to wield significant influence, particularly in religious matters, upholding Sunni orthodoxy against Ismaili and Shia sects.

The Assyrian people resisted Arabization, Turkification, and Islamization, remaining the majority population in northern Iraq until the 14th century. However, the massacres by Timur severely reduced their numbers, leading to the abandonment of the city of Assur. Following this period, indigenous Assyrians became an ethnic, linguistic, and religious minority in their homeland.

1258 JAN 1 – 1466

TURCO-MONGOL RULE OF MESAPOTAMIA

Iraq

Following the Mongol conquests, Iraq became a peripheral province of the Ilkhanate, leading to a decline in Baghdad’s prominence. The Mongols directly governed Iraq, the Caucasus, and western and southern Iran, with the exception of regions like Georgia, the Artuqid sultanate of Mardin, Kufa, and Luristan. The Qara’unas Mongols administered Khorasan autonomously, exempt from taxes, while the Kart dynasty in Herat also maintained its independence. Anatolia emerged as the wealthiest province of the Ilkhanate, contributing about a quarter of its revenue, while Iraq and Diyarbakir together accounted for approximately 35 percent.

In the 1330s, following the fragmentation of the Ilkhanate, the Jalayirids, a Mongol dynasty, ruled over Iraq and western Persia for roughly fifty years. Their decline was hastened by Tamerlane’s conquests and uprisings among the Qara Qoyunlu Turkmen, known as the “Black Sheep Turks.”

After Tamerlane’s death in 1405, there was a brief effort to revive the Jalayirid sultanate in southern Iraq and Khuzistan, but this revival was short-lived. Ultimately, the Jalayirids fell to the Kara Koyunlu, another Turkmen group, in 1432, marking the end of their rule in the region.

1258 JAN 1

MONGOL INVASION OF MESOPOTAMIA

Baghdad, Iraq

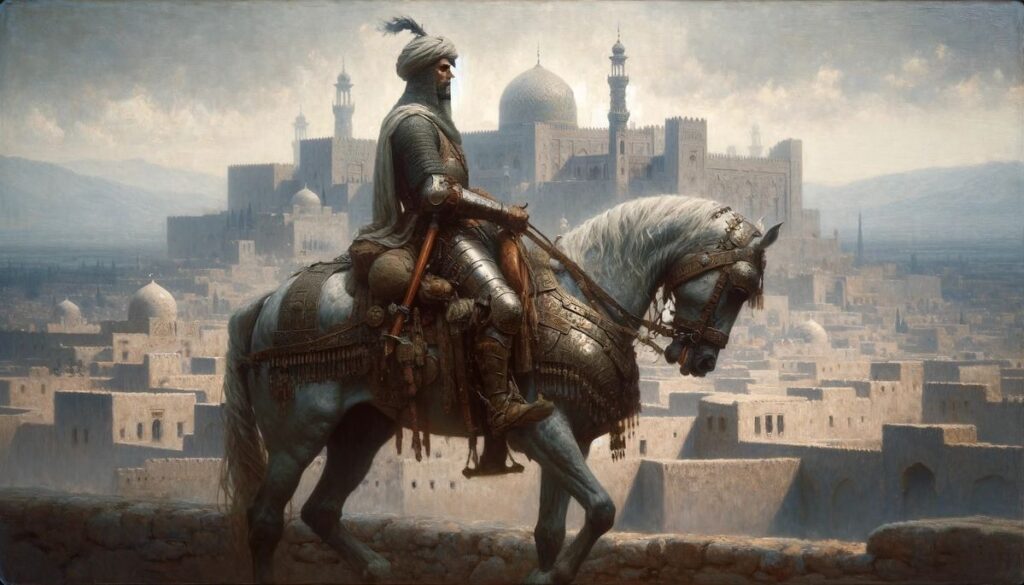

In the late 11th century, the Khwarazmian dynasty established control over Iraq, marking a period of Turkic secular rule alongside the Abbasid caliphate. This era came to an end with the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. The Mongols, under Genghis Khan, conquered Khwarezmia by 1221, but Iraq initially enjoyed a temporary reprieve due to Genghis Khan’s death in 1227 and the ensuing power struggles within the Mongol Empire. Mongke Khan resumed Mongol expansion in 1251, and when Caliph al-Mustasim refused to comply with Mongol demands, Baghdad was besieged by Hulagu Khan in 1258.

The Siege of Baghdad, a crucial event in the Mongol conquests, lasted for 13 days, from January 29 to February 10, 1258. Ilkhanate forces and their allies besieged, captured, and plundered Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate. This led to the massacre of a large portion of the city’s population, potentially numbering in the hundreds of thousands. The fate of the city’s libraries and their contents remains a topic of debate among historians. The Mongols executed Caliph al-Mustasim, resulting in significant depopulation and destruction in Baghdad. This siege symbolically marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age, a time during which the caliphs had extended their rule from the Iberian Peninsula to Sindh.

1508 JAN 1 – 1622

SAFAVID MESOPOTAMIA

Iraq

In the late 15th century, a significant shift in power occurred when the Aq Qoyunlu (White Sheep Turkmen) overthrew the Qara Qoyunlu (Black Sheep Turkmen) in 1466. This change paved the way for the rise of the Safavid dynasty, which would ultimately defeat the Aq Qoyunlu and gain control over Mesopotamia.

The Safavid dynasty, one of Iran’s most influential ruling houses, reigned from 1501 to 1736. Their rule is typically divided into two main periods: the first from 1501 to 1722, followed by a brief resurgence from 1729 to 1736. Some historians also identify a later phase of Safavid authority from 1750 to 1773.

At its height, the Safavid Empire was a powerful force in the region, controlling vast territories that extended well beyond modern-day Iran. Their domain included present-day Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Armenia, eastern Georgia, and parts of the North Caucasus (including regions now in Russia). The empire also encompassed Iraq, Kuwait, Afghanistan, and portions of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

This extensive territorial reach enabled the Safavid dynasty to exert significant influence over the cultural, political, and economic landscape of the region. Their reign represented a period of remarkable development and left a lasting impact on the history and heritage of the areas under their control.

1533 – 1918

OTTOMAN IRAQ

The Ottoman Empire’s rule over Iraq from 1534 to 1918 was a significant period in the region’s history. This era commenced with Suleiman the Magnificent’s capture of Baghdad in 1534, integrating Iraq into the empire’s expanding Middle Eastern territories.

Initially, the Ottomans organized Iraq into four administrative divisions known as vilayets: Mosul, Baghdad, Shahrizor, and Basra. Each vilayet was governed by a Pasha who reported directly to the Ottoman Sultan. This administrative structure aimed to firmly incorporate Iraq into the empire while still allowing for a degree of local autonomy.

The region’s strategic importance made it a key battleground during the Ottoman-Safavid Wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. The 1639 Treaty of Zuhab, which concluded one of these conflicts, established the borders between Iraq and Iran, many of which remain largely unchanged today.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Ottoman control over Iraq began to weaken. Local rulers, particularly the Mamluks in Baghdad (1704-1831), gained significant autonomy. Under leaders like Sulayman Abu Layla Pasha, the Mamluk period was marked by relative stability and economic growth.

The 19th-century Tanzimat reforms aimed at modernizing and centralizing the Ottoman Empire brought substantial changes to Iraq. These reforms included new administrative divisions, updates to the legal system, and efforts to curtail the power of local rulers.

A major development in the early 20th century was the construction of the Baghdad Railway, which connected Baghdad to Istanbul. This German-backed project sought to strengthen Ottoman authority and enhance economic and political ties.

Ottoman rule in Iraq came to an end after World War I and the empire’s defeat. The 1918 Armistice of Mudros and the subsequent Treaty of Sèvres led to the partitioning of Ottoman territories, placing Iraq under British control and marking the conclusion of the Ottoman era in Iraqi history.

1534 JAN 1 – 1639

OTTOMAN-SAFAVID WARS

Iran

The struggle for control of Iraq between the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Persia culminated in the pivotal Treaty of Zuhab in 1639, marking a significant chapter in the region’s history. This era was characterized by intense military conflicts, shifting political allegiances, and significant cultural and religious impacts, highlighting the rivalry between two of the most powerful empires of the 16th and 17th centuries, driven by geopolitical ambitions and sectarian differences between the Sunni Ottomans and Shia Persians.

The rise of the Safavid dynasty under Shah Ismail I in the early 16th century set the stage for prolonged conflict. The Safavids’ promotion of Shia Islam positioned them as ideological adversaries of the Sunni Ottoman Empire. This religious divide intensified the ensuing conflicts, as 1501 marked both the establishment of the Safavid Empire and the beginning of their campaign to propagate Shia Islam in opposition to Ottoman Sunni dominance.

The Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 marked the first significant military engagement between the two empires. Ottoman Sultan Selim I’s forces achieved a decisive victory over Shah Ismail, establishing Ottoman supremacy in the region and setting a precedent for future confrontations. Despite this initial defeat, Safavid influence continued to grow, especially in the eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire.

Iraq, with its religious significance for both Sunni and Shia Muslims and its strategic location, became a key battleground. The capture of Baghdad by Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in 1534 brought Iraq under Ottoman control, a notable achievement given Baghdad’s role as a major trade hub and religious center. However, control over Iraq fluctuated between the two empires throughout the 16th and 17th centuries as territories changed hands during various military campaigns.

Under Shah Abbas I, known for his military prowess and administrative reforms, the Safavids made significant territorial gains in the early 17th century. The recapture of Baghdad by Abbas I in 1623 was part of a broader Safavid strategy to reclaim lost territories, representing a substantial setback for the Ottomans and signaling a shift in the balance of power in the region.

The Treaty of Zuhab in 1639, signed between Ottoman Sultan Murad IV and Safavid Shah Safi, finally concluded this prolonged conflict. This landmark agreement established a new border between the two empires and had lasting implications for the region’s demographic and cultural landscape. The treaty effectively recognized Ottoman control over Iraq, with the boundary drawn along the Zagros Mountains, a delineation that largely defines the modern border between Turkey and Iran.

1704 JAN 1 – 1831

MAMLUK IRAQ

Iraq

The Mamluk era in Iraq, lasting from 1704 to 1831, represents a unique chapter in the region’s history, marked by relative stability and semi-autonomous governance within the Ottoman Empire. This period began under Hasan Pasha, a Georgian Mamluk, who transitioned the region from direct Ottoman Turkish control to a more localized form of administration.

Hasan Pasha’s reign (1704-1723) established the foundations of the Mamluk period in Iraq. He created a semi-independent state that maintained nominal allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan while exercising actual control over the area. His administration prioritized regional stabilization, economic revival, and administrative reforms, notably enhancing security along trade routes, which significantly boosted Iraq’s economy.

Following Hasan Pasha, his son Ahmad Pasha (1723-1747) continued these policies, leading to further economic growth and urban development, particularly in the expansion and prosperity of Baghdad.

The Mamluk rulers were distinguished for their military prowess, crucial in defending Iraq against external threats, especially from Persia. They maintained a strong military presence and leveraged their strategic position to exert regional influence.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, under leaders like Sulayman Abu Layla Pasha, effective governance continued in Iraq. These rulers implemented various reforms, including military modernization, the establishment of new administrative structures, and the promotion of agricultural development, which enhanced Iraq’s prosperity and stability, making it one of the more successful provinces within the Ottoman Empire.

However, the Mamluk rule faced persistent challenges, including internal power struggles, tribal conflicts, and tensions with the central Ottoman authority. The decline of the Mamluk regime began in the early 19th century, culminating in the Ottoman reconquest of Iraq in 1831 under Sultan Mahmud II. This military campaign, led by Ali Rıza Pasha, effectively ended the Mamluk era and reestablished direct Ottoman control over Iraq.

The post-Mamluk era in Iraq, extending from the early 19th to the early 20th century, was a time of significant transformation that reshaped the region’s political, social, and economic landscape. This period was characterized by the Ottoman Empire’s efforts to centralize power, the rise of nationalist sentiments, and increasing European influence, culminating in the dramatic events of World War I.

The Ottoman reconquest of Iraq in 1831, which ended the long-standing Mamluk rule, marked the beginning of a new administrative era. Sultan Mahmud II, as part of his broader modernization agenda known as the Tanzimat reforms, dismantled the Mamluk system that had governed Iraq for over a century. These reforms aimed to centralize authority and modernize the empire, resulting in the reorganization of provincial structures and the introduction of new legal and educational systems in Iraq. The ultimate goal was to integrate the region more closely into the Ottoman Empire.

By the mid-19th century, Iraq faced new challenges as it underwent significant socio-economic changes driven in part by growing European commercial interests. Urban centers like Baghdad and Basra evolved into important trade hubs, attracting European powers that established commercial ties and exerted economic influence. This period also witnessed the development of modern infrastructure, including railroads and telegraph lines, further connecting Iraq to global economic networks.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a pivotal moment for Iraq. As part of the Ottoman Empire, which had allied with the Central Powers, Iraq became a battleground between Ottoman and British forces. British interests in the region were driven by Iraq’s strategic location and the recent discovery of oil. The ensuing Mesopotamian campaign featured significant military engagements, including the Siege of Kut (1915-1916) and the Fall of Baghdad in 1917. These conflicts had devastating consequences for the local population, resulting in widespread suffering and loss of life.

1850 JAN 1 – 1900

ARAB NATIONALISM IN OTTOMAN IRAQ

Iraq

As the 19th century came to a close, Arab nationalism began to take root in Iraq, reflecting similar movements throughout the Ottoman Empire. This emerging nationalist sentiment was fueled by several factors: growing dissatisfaction with Ottoman governance, the influence of European ideologies, and a developing sense of distinct Arab identity. Intellectual and political leaders in Iraq and neighboring regions began advocating for greater autonomy, with some even calling for full independence. The Al-Nahda movement, a cultural renaissance, played a crucial role in shaping Arab intellectual discourse during this time.

The Ottoman Empire’s Tanzimat reforms, which aimed to modernize the state, inadvertently facilitated the influx of European ideas into the region. Arab thinkers such as Rashid Rida and Jamal al-Din al-Afghani eagerly embraced concepts like self-determination, spreading these ideas through emerging Arabic publications, including Al-Jawaa’ib. This intellectual awakening fostered a growing awareness of a shared Arab heritage and history.

Dissatisfaction with Ottoman rule created a fertile environment for these ideas to flourish. The increasingly centralized empire struggled to address the diverse needs of its subjects effectively. In Iraq, economic marginalization bred resentment among Arab communities, who felt excluded from the empire’s prosperity despite the region’s agricultural wealth. Additionally, religious tensions simmered, with the Shia majority facing discrimination and limited political influence. The concept of pan-Arabism, which promised unity and empowerment, resonated strongly with these disenfranchised groups.

Various uprisings across the empire further ignited Arab consciousness. While not explicitly nationalist, rebellions such as the Nayef Pasha uprising in 1827 and the Dhia Pasha al-Shahir revolt in 1843 demonstrated a growing defiance against Ottoman authority. In Iraq, figures like scholar Mirza Kazem Beg and Ottoman officer Mahmoud Shawkat Pasha, who was of Iraqi origin, advocated for local autonomy and modernization, setting the stage for future demands for self-determination.

Social and cultural changes also played a significant role in fostering this nascent nationalism. Rising literacy rates and the circulation of Arabic literature and poetry helped awaken a shared cultural identity. Tribal networks, traditionally focused on local loyalties, inadvertently provided a foundation for broader Arab solidarity, particularly in rural areas. Moreover, Islam, with its emphasis on community and unity, contributed to nurturing this growing Arab consciousness.

It is essential to recognize that Arab nationalism in 19th-century Iraq was not a singular movement but a complex and evolving phenomenon. While pan-Arabism offered a compelling vision of unity, distinct Iraqi nationalist currents would gain momentum in the 20th century. Nevertheless, these early stirrings, nurtured by intellectual awakenings, economic anxieties, and religious tensions, were instrumental in laying the groundwork for future struggles for Arab identity and self-determination within the Ottoman Empire and, later, in the independent nation of Iraq.

1914 NOV 6 – 1918 NOV 14

WORLD WAR I IN IRAQ

Mesopotamia, Iraq

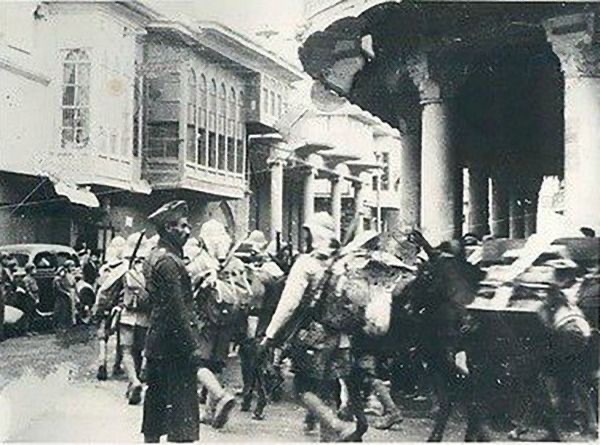

The Mesopotamian campaign was a crucial conflict in the Middle Eastern theater of World War I, featuring the Allies, primarily British Empire forces from Britain, Australia, and the British Raj, against the Central Powers, predominantly the Ottoman Empire. Initiated in 1914, the campaign initially aimed to protect Anglo-Persian oil interests in Khuzestan and the Shatt al-Arab. However, its objectives soon expanded to include capturing Baghdad and diverting Ottoman forces from other fronts. The campaign ended with the Armistice of Mudros in 1918, resulting in Iraq’s detachment from Ottoman control and contributing to the empire’s disintegration.

The conflict began with an Anglo-Indian amphibious landing at Al-Faw, quickly followed by a swift advance to secure Basra and nearby British oil fields in modern-day Iran. Allied forces achieved several victories along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, successfully defending Basra against an Ottoman counter-offensive at the Battle of Shaiba. However, the Allied advance stalled at Kut, south of Baghdad, in December 1916, culminating in a disastrous defeat during the subsequent Siege of Kut.

After regrouping, the Allies launched a renewed offensive aimed at capturing Baghdad. Despite fierce resistance from the Ottomans, the city fell in March 1917, followed by a series of Ottoman defeats that led to the Armistice of Mudros.

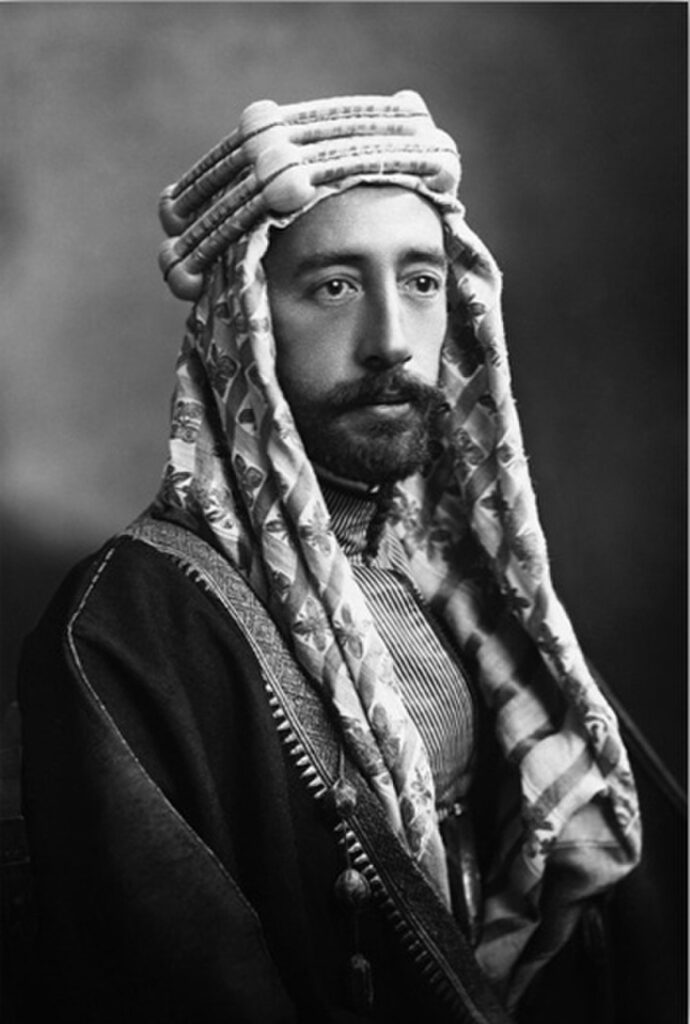

The end of World War I and the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in 1918 prompted a significant reconfiguration of the Middle East. The Treaties of Sèvres (1920) and Lausanne (1923) formalized the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire. In Iraq, this led to the establishment of a British mandate, sanctioned by the League of Nations, which marked the beginning of the modern Iraqi state, with borders defined by the British that included a diverse mix of ethnic and religious groups.

The British mandate faced numerous challenges, most notably the 1920 Iraqi revolt against British rule. In response, the 1921 Cairo Conference was convened, resulting in the decision to establish a Hashemite kingdom in Iraq under Faisal I, albeit with significant British influence. This marked the start of Iraq’s journey as a nominally independent state, heavily shaped by British interests and policies.

1920

CONTEMPORARY IRAQ

1920 MAY 1 – OCT

IRAQI REVOLT

Iraq

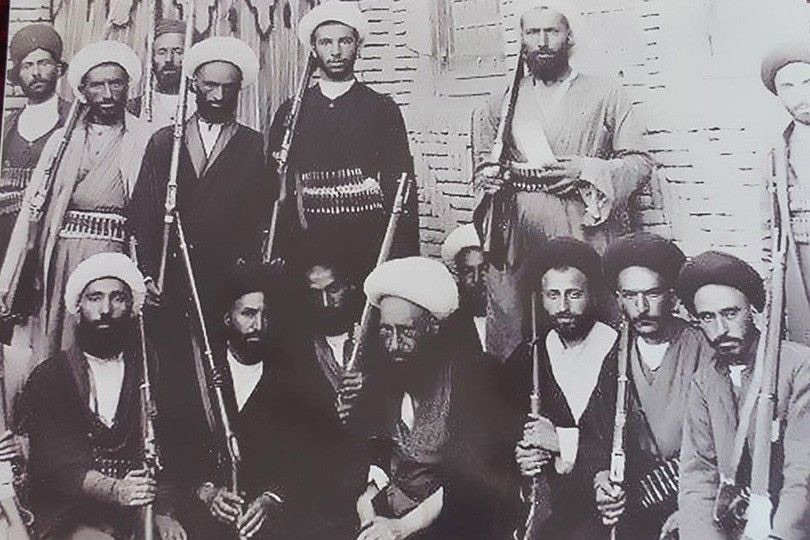

The Iraqi Revolt of 1920 erupted in Baghdad during the summer months, marked by widespread protests against British colonial rule. The immediate catalyst for these demonstrations was the British introduction of new land ownership laws and burial taxes in Najaf. The uprising quickly gained momentum, spreading through the predominantly tribal Shia regions along the middle and lower Euphrates. Sheikh Mehdi Al-Khalissi emerged as a prominent Shia leader during this revolt.

One of the most remarkable features of this uprising was the unprecedented cooperation among diverse groups, including Sunni and Shia religious communities, tribal factions, urban residents, and many Iraqi officers stationed in Syria at the time. The primary aims of the revolution were twofold: to achieve independence from British rule and to establish an Arab-led government.

Initially, the revolt made significant strides, but by late October 1920, British forces had largely quelled the main uprising, though pockets of resistance persisted sporadically until 1922. The British response was harsh, utilizing tactics such as aerial bombardment and punitive expeditions, resulting in substantial casualties among the Iraqi population.

While the southern uprisings unfolded, the 1920s in Iraq also witnessed revolts in the northern regions, particularly among the Kurdish population, driven by aspirations for independence and autonomy. Sheikh Mahmoud Barzanji emerged as a key Kurdish leader during this time, playing a significant role in the Kurdish struggle for self-determination.

These various uprisings in both the south and north highlighted the complex challenges facing the nascent state of Iraq. They underscored the difficulties in managing and integrating the different ethnic, religious, and sectarian groups within the newly established borders. The revolts also revealed deep-seated resentment against foreign rule and a strong desire for self-governance among various segments of Iraqi society.

The 1920 Revolt, in particular, left a lasting impact on Iraqi political consciousness. It is often viewed as a foundational moment in Iraq’s quest for independence and played a crucial role in shaping the political landscape in the subsequent decades. In response to these events, the British began to reconsider their approach to direct rule, eventually leading to the establishment of the Kingdom of Iraq under British mandate in 1921.

1921 JAN 1 – 1932

MANDATORY IRAQ

Iraq